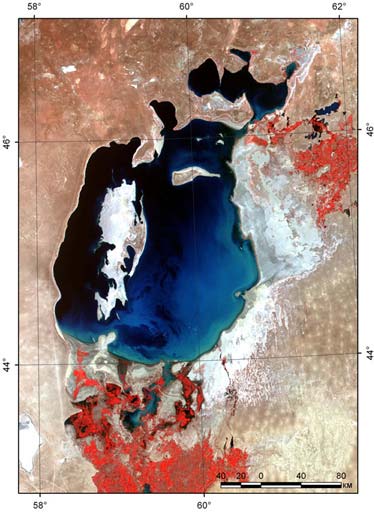

Aral SeaThe Aral Sea is a landlocked endorheic basin in Central Asia; it lies between Kazakhstan (Aktobe and Kyzylorda provinces) in the north and Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region of Uzbekistan, in the south. The name roughly translates as "Sea of Islands", referring to more than 1,500 islands of one hectare or more that once dotted its waters. There are now three lakes in the Aral Basin: the North Aral Sea and the eastern and western basins of the South Aral Sea. BackgroundOnce the world's fourth-largest inland sea with an area of 68,000 km2, the Aral Sea has been steadily shrinking since the 1960s, after the rivers Amu Darya and Syr Darya that fed it were diverted by Soviet Union irrigation projects. By 2004, the sea had shrunk to 25% of its original surface area, and a nearly fivefold increase in salinity had killed most of its natural flora and fauna. By 2007 it had declined to 10% of its original size, splitting into three separate lakes, two of which are too salty to support fish. The once prosperous fishing industry has been virtually destroyed, and former fishing towns along the original shores have become ship graveyards. With this collapse has come unemployment and economic hardship. The Aral Sea is also heavily polluted, largely as the result of weapons testing, industrial projects, pesticides and fertilizer runoff. Wind-blown salt from the dried seabed damages crops, and polluted drinking water and salt- and dust-laden air cause serious public health problems. The retreat of the sea has reportedly also caused local climate change, with summers becoming hotter and drier, and winters colder and longer.

The plight of the Aral Sea is frequently described as an environmental catastrophe. There is now an ongoing effort in Kazakhstan to save and replenish what remains of the northern part of the Aral Sea (the Small Aral). A dam project completed in 2005 has raised the water level of this lake by two metres. Salinity has dropped, and fish are again found in sufficient numbers for some fishing to be viable. The outlook for the far larger southern part of the sea (the Large Aral) remains bleak.

HistoryIn 1918, the Soviet government decided that the two rivers that fed the Aral Sea, the Amu Darya in the south and the Syr Darya in the northeast, would be diverted to irrigate the desert, in order to attempt to grow rice, melons, cereals, and cotton. This was part of the Soviet plan for cotton, or "white gold", to become a major export. This did eventually end up becoming the case, and today Uzbekistan is one of the world's largest exporters of cotton. The construction of irrigation canals began on a large scale in the 1940s. Many of the canals were poorly built, allowing water to leak or evaporate. From the Qaraqum Canal, the largest in Central Asia, perhaps 30 to 75% of the water went to waste. Today only 12% of Uzbekistan's irrigation canal length is waterproofed. By 1960, between 20 and 60 cubic kilometers of water were going each year to the land instead of the sea. Most of the sea's water supply had been diverted, and in the 1960s the Aral Sea began to shrink. From 1961 to 1970, the Aral's sea level fell at an average of 20 cm a year; in the 1970s, the average rate nearly tripled to 50–60 cm per year, and by the 1980s it continued to drop, now with a mean of 80–90 cm each year. The rate of water usage for irrigation continued to increase: the amount of water taken from the rivers doubled between 1960 and 2000, and cotton production nearly doubled in the same period. The Aral Sea fishing industry, which in its heyday had employed some 40,000 and reportedly produced one-sixth of the USSR's entire fish catch, essentially disappeared; so did the muskrat trapping in the deltas of Amu Darya and Syr Darya, which used to yield as much as 500,000 muskrat pelts a year. The disappearance of the lake was no surprise to the Soviets; they expected it to happen long before. As early as in 1964, Aleksandr Asarin at the Hydroproject Institute pointed out that the lake was doomed explaining, "It was part of the five-year plans, approved by the council of ministers and the Politburo. Nobody on a lower level would dare to say a word contradicting those plans, even if it was the fate of the Aral Sea." The reaction to the predictions varied. Some Soviet experts apparently considered the Aral to be "nature's error", and a Soviet engineer said in 1968 that "it is obvious to everyone that the evaporation of the Aral Sea is inevitable."[5] On the other hand, starting in the 1960s, a large scale project was contemplated to redirect part of the flow of the rivers of the Ob basin to Central Asia over a gigantic canal system. Refilling of the Aral Sea was considered as one of the project's main goals. However, due to its staggering costs and the negative public opinion in Russia proper, the federal authorities abandoned the project by 1986. Current situationFrom 1960 to 1998, the sea's surface area shrank by approximately 60%, and its volume by 80%. In 1960, the Aral Sea was the world's fourth-largest lake, with an area of approximately 68,000 km2 and a volume of 1100 km3; by 1998, it had dropped to 28,687 km2, and eighth-largest. The amount of water it has lost is the equivalent of completely draining Lakes Erie and Ontario. Over the same time period its salinity has increased from about 10 g/L to about 45 g/L. As of 2004, the Aral Sea's surface area was only 17,160 km2, 25% of its original size. By 2007 the sea's area had shrunk to 10% of its original size, and the salinity of the remains of the southern part of the sea (the Large Aral) had increased to levels in excess of 100 g/L. By comparison, the salinity of ordinary seawater is typically around 35 g/L; the Dead Sea's salinity varies between 300 and 350 g/L. Even the recently-discovered inflow of water discharge from underground into the Aral Sea will not in itself be able to stop the desiccation. This inflow of about 4 cubic kilometres per year is larger than previously estimated. This groundwater originates in the Pamirs and Tian Shan mountains and seeks its way through geological layers to a fracture zone at the bottom of the Aral Sea. In 1987, the continuing shrinkage split the lake into two separate bodies of water, the North Aral Sea (the Lesser Sea, or Small Aral Sea) and the South Aral Sea (the Greater Sea, or Large Aral Sea); an artificial channel was dug to connect them, but that connection was gone by 1999 as the two seas continued to shrink. In 2003, the South Aral further divided into eastern and western basins; the loss of the North Aral has since been partially reversed (see below). Shrinkage of the lake also created the Aralkum, a desert on the former lakebed. Work is being done to restore in part the North Aral Sea. Irrigation works on the Syr Darya have been repaired and improved to increase its water flow, and in October 2003, the Kazakh government announced a plan to build Dike Kokaral, a concrete dam separating the two halves of the Aral Sea. Work on this dam was completed in August 2005; since then the water level of the North Aral has risen, and its salinity has decreased. As of 2006, some recovery of sea level has been recorded, sooner than expected. "The dam has caused the small Aral's sea level to rise swiftly to 38 m (125 ft), from a low of less than 30 m (98 ft), with 42 m (138 ft) considered the level of viability." Economically significant stocks of fish have returned, and observers who had written off the North Aral Sea as an environmental catastrophe were surprised by unexpected reports that in 2006 its returning waters were already partly reviving the fishing industry and producing catches for export as far as Ukraine. The restoration reportedly gave rise to long absent rain clouds and possible microclimate changes, bringing tentative hope to an agricultural sector swallowed by a regional dustbowl, and some expansion of the shrunken sea. "The sea, which had receded almost 100 km south of the port-city of Aral, is now a mere 25 km away." There are plans to build a new canal to reconnect Aralsk with the sea. Construction is scheduled to begin in 2009, by which time it is hoped the distance to be covered will be only 6 km. A new dam is to be built based on a World Bank loan to Kazakhstan, with the start of construction also slated for 2009 to further expand the shrunken Northern Aral eventually to the withered former port of Aralsk. The South Aral Sea, which lies in poorer Uzbekistan, was largely abandoned to its fate. Projects in the North Aral at first seemed to bring glimmers of hope to the South as well: "In addition to restoring water levels in the Northern Sea, a sluice in the dike is periodically opened, allowing excess water to flow into the largely dried-up Southern Aral Sea." Discussions had been held on recreating a channel between the somewhat improved North and the desiccated South, along with uncertain wetland restoration plans throughout the region, but political will is lacking. Uzbekistan shows no interest in abandoning the Amu Darya river as an abundant source of cotton irrigation, and instead is moving toward oil exploration in the drying South Aral seabed. Vast salt plains exposed with the shrinking of the Aral have produced dust storms, making regional winters colder and summers hotter. Attempts to mitigate these effects include planting vegetation in the newly exposed seabed. In the Northern Aral, recently higher sea levels have slightly moderated these effects in some areas, and the spring season now sees long-missing rainfall. As of summer 2003, the South Aral Sea was vanishing faster than predicted. In the deepest parts of the sea, the bottom waters are saltier than the top, and not mixing. Thus, only the top of the sea is heated in the summer, and it evaporates faster than would otherwise be expected. Based on the recent data, the western part of the South Aral Sea is expected to be gone within 15 years; the eastern part could last indefinitely. The ecosystem of the Aral Sea and the river deltas feeding into it has been nearly destroyed, not least because of the much higher salinity. The receding sea has left huge plains covered with salt and toxic chemicals, which are picked up and carried away by the wind as toxic dust and spread to the surrounding area. The land around the Aral Sea is heavily polluted and the people living in the area are suffering from a lack of fresh water and health problems, including high rates of certain forms of cancer and lung diseases. Crops in the region are destroyed by salt being deposited onto the land. The town of Moynaq in Uzbekistan had a thriving harbor and fishing industry that employed approximately 60,000 people; now the town lies miles from the shore. Fishing boats lie scattered on the dry land that was once covered by water, many have been there for 20 years. The only significant fishing company left in the area has its fish shipped from the Baltic Sea, thousands of kilometres away. The tragedy of Aral coast was portrayed in the 1989 film, Psy ("Dogs"), by Soviet director, Dmitriy Svetozarov. The film was shot on location in the actual ghost town, showing scenes of abandoned buildings and scattered vessels. More recently, in 1999, German filmmaker Joachim Tschirner has produced the documentary "Der Aralsee" for the channel Arte. On 9/10 June 2007 BBC World broadcast a documentary called 'Back From The Brink?' made by Borna Alikhani and Guy Creasey that showed some of the changes in the region since the introduction of the Aklak Dam. Possible solutionsMany different solutions to the different problems have been suggested over the years, ranging in feasibility and cost, including the following:

Source: Wikipedia |