Section 12. Thematic reviews

12.1. Climate Change

State of Climate in 2023

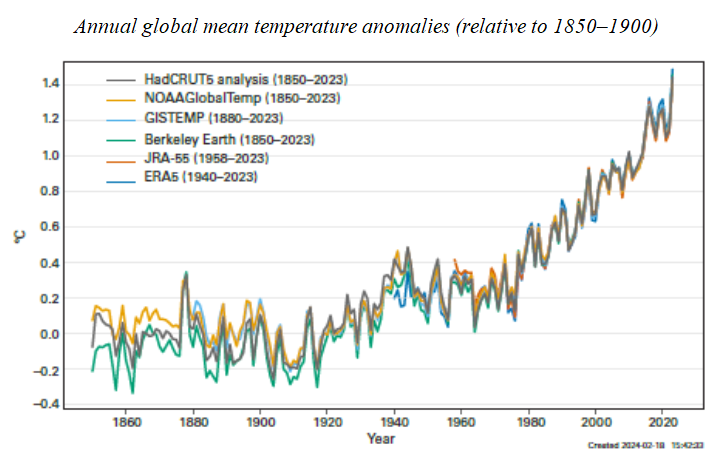

According to WMO annual report, 2023 was the warmest year on record. Records were once again broken, and in some cases smashed, for greenhouse gas levels, surface temperatures, ocean heat and acidification, sea level rise, Antarctic sea ice cover and glacier retreat. 2023 has shown that ongoing climate change is having an increasing impact on our planet.

Key messages

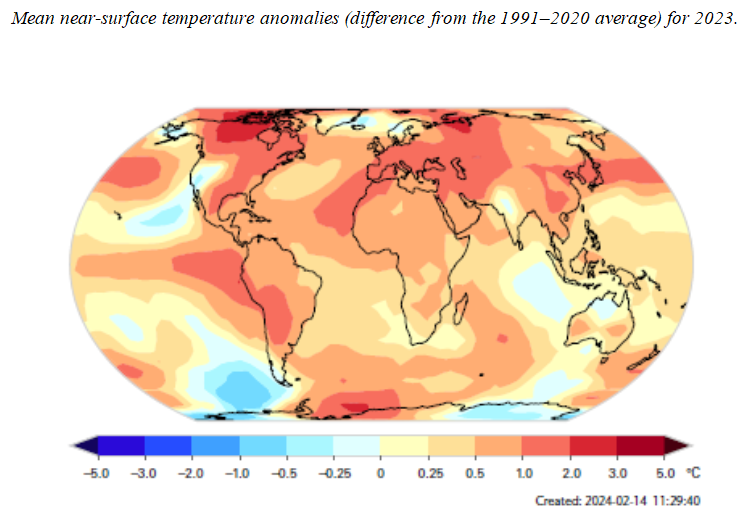

Temperature. 2023 was the warmest year in the 174-year observational record: the global mean near-surface temperature in 2023 was 1.45 + 0.12 oC above the 1850–1900 average. It also clearly surpassed the previous joint warmest years, 2016 at 1.29 + 0.12 oC above the 1850-1900 average and 2020 at 1.27 + 0.13 oC. The long-term increase in global temperature is due to increased concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The shift from La Nina to fully developed El Nino conditions in mid-2023 likely explains some of the rise in temperature from 2022 to 2023.

Greenhouse gases. Concentrations of the three main greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide – reached record-high observed levels in 2022 and continued to increase in 2023.

Glaciers. 2023 showed the largest loss of ice on record (1950-2023), driven by extremely negative mass balance in both western North America and Europe. Glaciers in western North America and the European Alps experienced an extreme melt season. In Switzerland, glaciers have lost about 10% of their remaining volume in the past two years. Western North America experienced record glacier mass loss at rates that were five times higher than rates measured for the period 2000–2019. Glaciers in western North America lost an estimated 9% of their 2020 volume over the period 2020–2023.

Ocean. In 2023, ocean heat content reached its highest level. It is expected that warming will continue – a change that is irreversible on centennial to millennial timescales.

Most of the global ocean from roughly 20o N to 20o S of the equator had been in a marine heatwave state since early November. Of note in 2023 were the persistent and widespread marine heatwaves in the North Atlantic, which began in the northern hemisphere spring, peaked in extent in September and persisted through the end of the year, with temperature anomalies in the open ocean of +3 oC. The Mediterranean Sea experienced near-complete coverage of strong and severe marine heatwaves for the twelfth consecutive year.

The ocean acidification increases as a result of absorption of CO2.

Sea level. In 2023, global mean sea level reached a record high in the satellite record (from 1993 to present), reflecting continued ocean warming as well as the melting of glaciers and ice sheets. The rate of global mean sea-level rise in the past 10 years (2014–2023) is more than twice the rate of sea-level rise in the first decade of the satellite record (1993–2002).

Socio-economic and environmental impacts

Extreme weather had major impacts on all inhabited continents in 2023.

Long-term drought persisted in North-western Africa and parts of the Iberian Peninsula, as well as in parts of Central and South-West Asia, and intensified in many parts of Central America, northern South America and the southern United States. In Uruguay, water storages reached critically low levels, badly affecting the quality of supplies to major centers, including Montevideo.

Flooding. Flooding associated with extreme rainfall from Mediterranean Cyclone Daniel affected Greece, Bulgaria, Türkiye and Libya. Tropical Cyclone Freddy in February and March was one of the world’s longest-lived tropical cyclones impacting severely Madagascar, Mozambique and Malawi.

Heatwaves. Many significant heatwaves occurred in various parts of the world, especially in the second half of July, when severe and exceptionally persistent heat occurred in southern Europe and North Africa, including: 48.2°C in Italy; 49.0°C in Tunis; 50.4°C in Morocco; 49.2°C in Algeria. This caused extensive wildfire activity during the summer, particularly in Greece, where 96,000 ha were burned.

The deadliest single wildfire of the year occurred in Hawaii, where at least 100 deaths were reported.

Food insecurity. The number of people who are acutely food insecure worldwide has more than doubled, from 149 million people before the COVID-19 pandemic to 333 million people in 2023. Although global hunger levels remained unchanged from 2021 to 2022. However, they are still far above pre-COVID 19 pandemic levels: in 2022, 9.2% of the global population (735.1 million people) were undernourished.

Protracted conflicts, economic downturns and high food prices are at the root of high global food insecurity levels. High food prices are exacerbated by the high costs of agricultural inputs, driven by ongoing and widespread conflict around the world, and high global food insecurity levels are aggravated by the effects of climate and weather extremes. In southern Africa, for example, weather extremes, including the passage of Cyclone Freddy, have affected areas of Madagascar, southern Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe and caused severe damage on crops and economy. Afghanistan experienced a substantial reduction in snowmelt and rainfall, resulting in another poor crop season. Between May and October, 15.3 million Afghans were estimated to face severe acute food insecurity, especially in the north and northeast of the country. The return of El Niño in 2023 led to adverse consequences through the entire crop cycle of maize in Central America and northern parts of South America, where water deficits and high temperature had negative impacts on final production, particularly for smallholders and more vulnerable households in the Dry Corridor. Floods in July affected the main cropland areas in Libya, which was already in a state of food crisis and in need of external assistance.

Climate and Water Resources

Record temperatures across most of the world in 2023 also affected the global water cycle, from intensifying cyclones and other rainfall systems, to exacerbating drought and fire activity. In 2023, the Global Water Monitor Consortium published its second annual report.

Key messages

Precipitation was close to average. There does not appear to be a clear trend towards more monthly high or low rainfall extremes. However, total precipitation in 2023 was unusually high in some regions at high northern latitudes (including Arctic Canada and parts of northern Europe), the Arabian Peninsula, the Horn of Africa, south Asia and the Himalayas.

Rainfall was unusually low in the southern half of Canada, Central America, the north and east of South America, the western Mediterranean, and Central Asia. Annual rainfall was unusually low in Mexico, Turkmenistan and Marocco.

The lowest annual rainfall since 1979 was recorded for six river basins in Canada, the Sao Francisco River in eastern Brazil, along the Central American coast, the Aral Basin. Record high annual precipitation was observed in several Arctic basins, as well as river catchments in Sweden and the Tibet Plateau.

Air humidity. Air humidity over land was the second lowest on record, continuing a trend towards drier average and extreme conditions. A total of 20 countries and territories experienced unusually low air humidity (σ<-2) in 2022. They include Russia, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan in Central Asia, five countries and territories in the Caribbean, five in South America (including Brazil), three in North-Africa, Sudan and South Sudan in Eastern Africa.

Soil water. Despite warmer and drier conditions, high annual soil water conditions were observed in many regions, with relatively wet soils across Europe, South and Eastern Asia, the western USA and Northern Australia.

Very dry soil conditions occurred in Central Asia (especially in Turkmenistan), the south of South America and in some regions in high northern latitudes.

Surface water occurrence. In 2023, global surface water occurrence was the second lowest in two decades, but months with record high water occurrence appear to be increasing globally. Annual water occurrence was average or below average in most countries. Water extent was unusually low for Turkmenistan due to ongoing water level declines in the Caspian Sea and in the Falkland Islands. Water occurrence was extremely high in Ethiopia, South Sudan and Egypt due to high rainfall in the Upper Nile. Water occurrence was also unusually high in 14 other countries, including India and Nepal in Asia, Guinea-Bissau and Chad in Africa, Cuba and several smaller island states.

River flows. In 2023, global river flows were slightly lower than the previous year. River flows were: (1) extremely high in both Congo’s and unusually high and/or the highest since 2003 in Nigeria, the Central African Republic and Ethiopia in Africa, the UK, Ireland and Denmark in Europe, El Salvador and Ecuador in the Americas, Iran and Azerbaijan in Asia, and in New Zealand; (2) low and/or the lowest since 2003 in Georgia, Bhutan and Myanmar in Asia and Colombia in South America.

Terrestrial water storage was unusually low in much of North and Central America, the Mediterranean region, North Africa, Central Asia, and parts of China and South Asia. Long-term declines in Caspian Sea level and retreating mountain glaciers play a role in some of these regions. Terrestrial water storage was unusually high in most of the northern high latitudes, as well as isolated parts of South America, Africa and Oceania.

Climate Change Agreement

As of February 2023, 198 members of UNFCCC, which represent over 98% of global GHG emissions, are parties to the Paris agreement. China and USA are the largest emitters of CO2 among the members of the UNFCCC. Since 2020, countries have been submitting their national action programs on climate change, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

Implementation of Paris Agreement in CA

All five Central Asian countries ratified the Paris Agreement to address the climate change threats and take appropriate measures. This necessitates a profound transformation of national energy systems, requiring substantial investments in sustainable infrastructure. Crucially, achieving climate goals demands that national development plans are fully aligned with ambitious climate action targets.

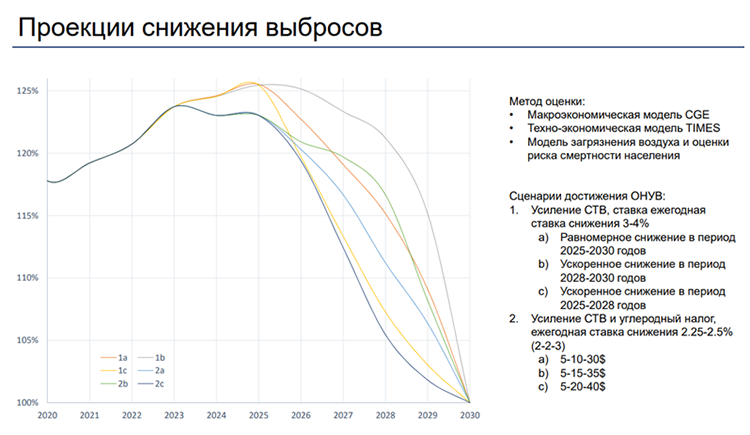

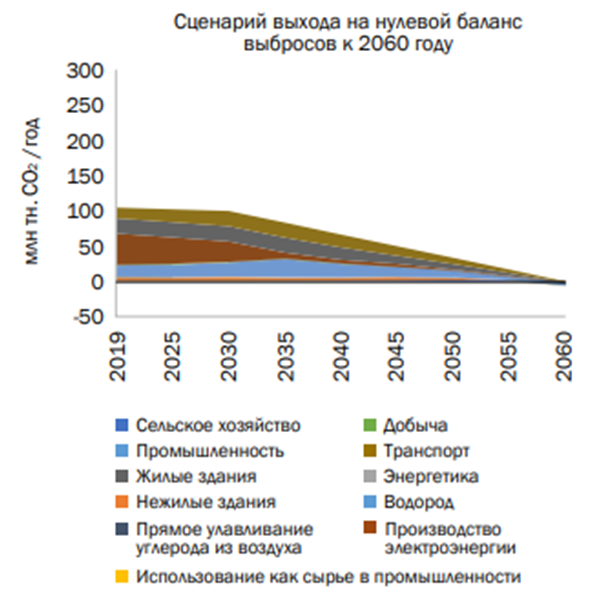

Kazakhstan ratified the Paris Agreement in November 2016 and set the goal to mitigate climate change at the net zero level by adopting a carbon neutrality strategy for 2060. In 2023, Kazakhstan launched its updated NDC, which included an unconditional target of reducing GHG emissions by 15% by the end of 2030 relative to 1990 base year. The country has adopted the Development Strategy of the Republic of Kazakhstan until 2050, the Environmental Code, the Emissions trading system and the taxonomy of green projects that contribute to transition to RES. Thus, the Government has set the goal that the share of RES in electricity production shell be increased to 15% by 2030 and to 50% by 2050.

Scenarios for achieving NDCs of Kazakhstan by 2030

Kyrgyz Republic submitted its updated NDC in October 2021. The Republic has committed to unconditionally reduce GHG emissions by 16.63% by 2025 and by 15.97% by 2030, under the business-as-usual scenario. Should international support be provided, GHG emissions will be reduced by 36.61% by 2025 and by 43.62% by 2030. The country has developed and is implementing the following strategic documents related to the NDC: National Development Strategy of the Kyrgyz Republic for 2018-2040, Climate Investment Program of the Kyrgyz Republic and Program for the Development of a Green Economy in the Kyrgyz Republic for 2019-2023. In 2025, some adaptation measures of NDC will be revisited for 2026-2030.

Tajikistan launched its updated NDC in October 2021. In line with this NDC, the country is committed to reduce GHG emissions by 40-50% subject to an international funding by 2030 (against 1990). The unconditional contribution (NDC) of reducing GHG in Tajikistan is to reduce GHG by 30-40% by 2030 (against 1990) through enhanced adaptation in energy, water, agriculture, forestry and transport sectors. The National Development Strategy of Tajikistan until 2030, the Mid-Term Development Program (MDP) of the Republic of Tajikistan for the period of 2021-2025, the National Strategy of Tajikistan for Disaster Risk Reduction for 2019-2030 and the National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change until 2030 have been developed and are implemented in the country.

Turkmenistan in its second NDC submitted in 2022 commits to reduce GHG emissions by 20% by 2030 (against 2010). GHG emissions increased in Turkmenistan from 58.4 MtCO2 in 2010 and 63 MtCO2 in 2020 to 65.7 MtCO2 in 2021. The specified target covers economy as a whole, including energy, industry, agriculture. It embraces CO2, CH4, N2O and foamed plastic emissions. Turkmenistan also declared the adaptation measures until 2030, in particular, increase resilience and reduce vulnerability to climate change to achieve sustainable economic growth. For this, the country needs about $500 million of international support.

Uzbekistan submitted the updated NDC in October 2021. The goal is to reduce by 2030 specific greenhouse gas emissions per unit of GDP by 35% from the level of 2010. This is more than in the first NDC, which outlined the reduction by 10%. The updated NDC also increases adaptation, especially in agriculture. Additionally, the country works to align the NDC with the Strategy for Transition of the Republic of Uzbekistan to a Green Economy by 2030. The NDC goals are to be achieved by increasing the share of RES in power production to 25%, deploy alternative fuel types in the transport sector, improve solid waste management, promote energy-saving technologies in all economic sectors, expand forest areas, etc.

Climate Change Conference 28

The 28th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28) took place under the motto ‘Climate action can’t wait’ in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, from 30 November to 13 December 2023. Participants from almost 200 countries have recognized the need to transit away from fossil fuel. Thus, COP28 was marked by the adoption of the UAE Consensus, an ambitious document, which addressed all key aspects of climate policy. With this Consensus, the parties have committed to the following:

tripling renewable energy capacity globally and doubling the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030

accelerating efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power

accelerating global efforts to develop and deploy zero-emission energy systems powered by zero- and low-carbon fuels, targeting widespread adoption well before mid-century

transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science

accelerating zero- and low-emission technologies, including, inter alia, renewables, nuclear, abatement and removal technologies such as carbon capture and utilisation and storage, particularly in hard-to-abate sectors, and low-carbon hydrogen production

accelerating and substantially reducing non-carbon-dioxide emissions globally, including in particular methane emissions by 2030

accelerating reductions in road transport emissions across all fronts, including by rapidly expanding infrastructure for and deploying zero- and low-emission vehicles

phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transitions, as soon as possible

Other COP28 outcomes

For the first time in UNFCCC conferences, COP28 addressed such areas as health, trade, relief, recovery and peace. The outcomes were as follows:

• in order to work towards ensuring better health outcomes, including through the transformation of health systems to be climate-resilient, low-carbon, sustainable and equitable, and to better prepare communities and the most vulnerable populations for the impacts of climate change, the countries united and signed the COP 28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health;

• The loss and damage fund designed to support climate-vulnerable developing countries was brought to life ; countries have pledged $3.5 billion to replenish the resources of the Green Climate Fund. At the GCF’s High-level Pledging Conference in Bonn in October 5, 2023, 25 countries pledged their support to GCF totaling $9.3 billion;

• COP 28 Presidency also launched the UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action; more than $2.5 billion has been mobilized by the global community to support food security and the UAE and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation launched a partnership for Food Systems, Agriculture Innovation and Climate Action;

• 72 countries and 39 organizations joined the newly created Coalition for High Ambition Multilevel Partnership (CHAMP) for Climate Action. The Coalition aims to enhance cooperation, where applicable and appropriate, with subnational governments in the planning, financing, implementation, and monitoring of climate strategies;

• the COP 28 Gender-Responsive Just Transitions and Climate Action Partnership was launched. This partnership represents a package of commitments in support of the goals of the enhanced Lima Work Program on Gender and its Gender Action Plan. Kyrgyzstan joined the partnership among the Central Asian countries;

• 38 countries signed the UNESCO Declaration on the common agenda for education and climate change, where they committed to incorporate climate education into their NDCs and national adaptation plans. Uzbekistan is one of founding partners of the Declaration;

• 43 countries and the European Union have joined the Freshwater Challenge, committing to conserve and restore 30% of degraded freshwater ecosystems. Tajikistan joined this Challenges among the Central Asia countries.

Central Asian countries at COP28

For the CA countries COP28 has started from the presentation of the Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Central Asia. The document outlines four strategic objectives: (1) strengthen regional coordination for climate change; (2) create mechanisms for the development and implementation of adaptation projects/programs and attraction of financing; (3) improve adaptive capacity through accumulation and sharing of knowledge and scientific cooperation; (4) develop climate monitoring, information exchange and forecasting systems.

During the 10th meeting of representatives from the MFAs and Parliamentarians of Central Asian countries, a regional statement on combating climate change was presented. This statement holds significant importance for the countries of the region and the global negotiation process. It strengthens the collective voice of the region, promotes regional cooperation and partnerships, demonstrates a shared commitment, and enhances the effectiveness of global negotiations.

Climate Change Reports

WMO has published the Global Climate 2011-2020: A Decade of Acceleration report. This multi-agency effort provides a summary of the state of climate, extreme events and their socio-economic impacts from 2011-2020. The 2011-2020 report is the second in the series of the report, following the first decadal analysis from 2001-2010.

IPCC has released its sixth assessment report, AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. The report highlights the shrinking window of opportunity to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C and the escalating climate-related risks. Global temperatures could increase by up to 4°C, leading to severe consequences such as heightened water scarcity, food shortages, and declines in well-being and health. Addressing these challenges requires transitioning away from fossil fuels and significantly increasing investments in renewable energy.

10 New Insights in Climate Science 2023/2024

1. Overshooting 1.5°C is fast becoming inevitable. Keeping global mean temperature rise within 1.5°C is only possible in the near term with immediate, transformative action that rapidly decarbonises the economy, energy and land-use systems, cutting emissions by 43% by 2030 relative to 2019 levels.

2. A rapid and managed fossil fuel phase-out is required to stay within the Paris Agreement target range. Governments and the private sector must stop enabling new fossil fuel projects, accelerate the early retirement of existing infrastructure, and rapidly increase the pace of renewable energy deployment. High-income countries must lead the transition and provide support for low-income countries.

3. Robust policies are critical to attain the scale needed for effective carbon dioxide removal (CDR). Meeting the Paris Agreement’s targets will require scaling up CDR from a current level of about 2 billion tonnes of CO₂ to at least 5 billion tonnes or more by 2050. Today, virtually all CDR consists of afforestation and reforestation. Only 0.1% of current removals come from the rest of deployed methods, such as direct air capture and storage, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, enhanced weathering, etc. However, almost all scenarios that limit warming to 1.5°C or 2°C rely on large-scale deployment of these CDR methods.

4. Over-reliance on natural carbon sinks is a risky strategy: their future contribution is uncertain. Until now, land and ocean carbon sinks have grown in tandem with increasing CO₂ emissions, but research is revealing that carbon sinks may well absorb less carbon in the future than has been presumed from existing assessments. Therefore, emission reduction efforts have immediate priority, with nature-based solutions serving to increase carbon sinks in a complementary role to offset hard-to-abate emissions.

5. Joint governance is necessary to address the interlinked climate and biodiversity emergencies. The international conventions on climate change and biodiversity must find better alignment. Ensuring that the allocation of climate finance has nature-positive safeguards, and strengthening concrete cross-convention collaboration, are examples of key actions in the right direction.

6. Compound events amplify climate risks and increase their uncertainty. “Compound events” refer to a combination of multiple drivers and/or hazards (simultaneous or sequential), and their impacts can be greater than the sum of individual events. Crops are particularly sensitive to the simultaneous occurrence of extreme hot and dry conditions. Early spring followed by a late frost, can also harm crops. Given that a large proportion of crops are grown in just a few breadbasket regions, global food security is threatened. Therefore, identifying and preparing for specific compound events is crucial for robust risk management and providing support in emergency situations.

7. Mountain glacier loss is accelerating. New global glacier projections estimate that glaciers will lose between 26% (at +1.5°C) and 41% (at +4°C) of their current volume by 2100. This threatens populations downstream with water shortages in the longer term (approximately 2 billion worldwide), and exposes mountain dwellers to increased hazards, such as flash flooding.

8. Human immobility in areas exposed to climate risks is increasing. People facing climate risks may be unable or unwilling to relocate, and existing institutional frameworks do not account for immobility and are insufficient to anticipate or support the needs of these populations.

9. New tools to operationalize justice enable more effective climate adaptation. Monitoring the distinct dimensions of justice and incorporating them as part of strategic climate adaptation planning and evaluation can build resilience to climate change and decrease the risk of maladaptation.

10. Reforming food systems contributes to just climate action. Food systems are responsible for 31% of global GHG emissions and are capable of pushing global warming towards 2°C by 2100 barring significant changes to the status quo. At the same time, over 700 million people face hunger, and marginalised groups are disproportionately affected by food insecurity. Sustainability transformations research shows that fundamental food systems change might take decades, so action cannot be delayed any further. Sufficiency, regeneration, distribution, commons and care are guiding principles to steer the restructuring of food systems.

UNEP has published the 14th edition of the Emissions Gap Report for 2023 entitled “Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record – Temperatures hit new highs, yet world fails to cut emissions (again).” The report concludes that 2023 was marked by broken records and unmet commitments: greenhouse gas emissions remain high, global temperatures reached unprecedented levels, and the impacts of climate change are intensifying and accelerating. Moreover, financial resources intended to support vulnerable communities in adapting to climate change remain undisbursed.

Key messages:

1. Global GHG emissions set new record of 57.4 GtCO2e in 2022. Global GHG emissions increased by 1.2% from 2021 to 2022 to reach a new record of 57.4 GtCO2e. Global primary energy consumption expanded mainly through a growth in coal, oil and renewable electricity supply – whereas gas consumption declined by 3% following the energy crisis and the war in Ukraine. Investments in fossil fuel extraction and use have continued in most regions worldwide.

2. Current and historical emissions are highly unequally distributed within and among countries, reflecting global patterns of inequality. Per capita territorial GHG emissions vary significantly across countries. They are more than double the world average of 6.5 tons of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) in the Russian Federation and the United States of America, while those in India remain under half of it.

3. There has been negligible movement on NDCs since COP 27, but some progress in NDCs and policies since the Paris Agreement was adopted. If all new and updated unconditional NDCs are fully implemented, they are estimated to reduce global GHG emissions by about 5.0 GtCO2e annually by 2030, compared with the initial NDCs. The combined effect of the nine NDCs submitted since COP 27 amounts to around 0.1 GtCO2e of this total. Thus, while NDC progress since COP 27 has been negligible, progress since the adoption of the Paris Agreement is more pronounced, although still insufficient to narrow the emissions gap.

4. The number of net-zero pledges continues to increase, but confidence in their implementation remains low. As at 25 September 2023, 97 Parties covering approximately 81% of global GHG emissions had adopted net-zero pledges either in law (27 Parties), in a policy document such as an NDC or a long-term strategy (54 Parties), or in an announcement by a high-level government official (16 Parties). Responsible for 76 per cent of global emissions, all G20 members except Mexico have set net-zero targets. However, most concerningly, none of the G20 members are currently reducing emissions at a pace consistent with meeting their net-zero targets.

5. The emissions gap in 2030 remains high: current unconditional NDCs imply a 14 GtCO2e gap for a 2°C goal and a 22 GtCO2e gap for the 1.5°C goal. The additional implementation of the conditional NDCs reduces these estimates by 3 GtCO2e. The emissions gap is defined as the difference between the estimated global GHG emissions resulting from full implementation of the latest NDCs and those under least-cost pathways aligned with the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. The emissions gap for 2030 remains largely unchanged compared with last year’s assessment. Full implementation of unconditional NDCs is estimated to result in a gap with below 2°C pathways of about 14 GtCO2e (range: 13-16) with at least 66% chance.

6. Action in this decade will determine the ambition required in the next round of NDCs for 2035, and the feasibility of achieving the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. Global ambition in the next round of NDCs must be sufficient to bring global GHG emissions in 2035 to the levels consistent with below 2°C and 1.5°C pathways of 36 GtCO2e (range: 31-39) and 25 GtCO2e (range: 20-27) respectively, while also compensating for excess emissions until levels consistent with these pathways are achieved. In contrast, a continuation of current policies and NDC scenarios would result in widened and likely unbridgeable gaps in 2035.

7. If current policies are continued, global warming is estimated to be limited to 3°C. Delivering on all unconditional and conditional pledges by 2030 lowers this estimate to 2.5°C, with the additional fulfillment of all net-zero pledges bringing it to 2°C. Even in the most optimistic scenario, the chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C is only 14%, and the various scenarios leave open a large possibility that global warming exceeds 2°C or even 3°C. This further illustrates the need to bring global emissions in 2030 lower than levels associated with full implementation of the current NDCs, to expand the coverage of net-zero pledges to all GHG emissions and to achieve these pledges.

8. The failure to stringently reduce emissions in high-income countries and to prevent further emissions growth in low- and middle-income countries implies that all countries must urgently accelerate economy-wide, low-carbon transformations to achieve the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. Energy is the dominant source of GHG emissions, currently accounting for 86% of global CO2 emissions. Global transformation of energy systems is thus essential, including in low- and middle-income countries, where pressing development objectives must be met alongside a transition away from fossil fuels.

9. Low- and middle-income countries face substantial economic and institutional challenges in low-carbon energy transitions, but can also exploit opportunities. Access to affordable finance is therefore a prerequisite for increasing mitigation ambition in low- and middle-income countries. Yet, costs of capital are up to seven times higher in these countries compared with the United States of America and Europe. International financial assistance will therefore have to be significantly scaled up from existing levels, and new public and private sources of capital better distributed towards low-income countries, restructured through financing mechanisms that lower costs of capital. These include debt financing, increasing long-term concessional finance, guarantees and catalytic finance.

10. Further delay of stringent global GHG emissions reductions will increase future reliance on CDR to meet the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. CDR is necessary to achieve the long-term goal of the Paris Agreement as reaching net-zero CO2 emissions is required to stabilize global warming, whereas net-zero GHG emissions will result in a peak and decline in global warming. CDR is already deployed today – mainly in the form of conventional land-based methods, such as afforestation, reforestation and management of existing forests, with a large share located in developing countries. Present-day direct removals through conventional land-based methods are estimated to be 2.0 (±0.9) GtCO2 annually, almost entirely through conventional land-based methods.

Significant and Major Events

The UNGA adopted a resolution that asks the International Court of Justice for an opinion on whether countries have a legal duty to address climate change and what the legal consequences of climate inaction could be. The resolution came as a growing number of people around the world turned to courts to compel governments and businesses to act on climate change.

Global trends in climate change litigation. Climate-related lawsuits have more than doubled since 2017 according to the Global Climate Litigation Report: 2023 Status Review. While most cases have been brought in the US, climate litigation is taking root all over the world, with about 17 per cent of cases now being reported in developing countries, including Small Island Developing States.

34 cases have been brought by and on behalf of children and youth under 25 years old, including by girls as young as seven and nine years of age in Pakistan and India respectively, while in Switzerland, plaintiffs are making their case based on the disproportionate impact of climate change on senior women. Globally, 55% of cases have had a climate-positive ruling.

Most ongoing climate litigation falls into one or more of six categories: 1) cases relying on human rights enshrined in international law and national constitutions; 2) challenges to domestic non-enforcement of climate-related laws and policies; 3) litigants seeking to keep fossil fuels in the ground; 4) advocates for greater climate disclosures and an end to greenwashing; 5) claims addressing corporate liability and responsibility for climate harms; and 6) claims addressing failures to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Remarkable climate change litigation cases in 2023

105 United Nations member countries led by a Pacific Island nation Vanuatu, asked the International Court of Justice to issue an opinion that would clarify the rights and responsibilities of states with regard to climate action. While the opinion will be nonbinding, it would clarify what obligations countries have under international law to tackle climate change and it would become more accessible for individuals to take governments to court.

A state court in Montana ruled in favor of 16 young people who had sued the state government, arguing that policies favoring fossil fuels had violated their constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment. Although the state has appealed the ruling, the verdict nevertheless marks an important precedent for those who are trying to use the legal system to address climate change.

21 youth plaintiffs in the landmark federal constitutional climate lawsuit, Juliana v. United States dismissed or delayed for over eight years, are currently moving forward toward trial on the question of whether the federal government’s fossil fuel-based energy system, and resulting climate destabilization, is unconstitutional.

18 young Californians filed a case against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). They allege that the EPA has been allowing dangerous levels of climate pollution, thereby harming and discriminating against them.

The Native American tribes - Makah Indian Tribe and the Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe - filed the first climate deception lawsuits against fossil fuel giants such Exxon Mobil, Shell, and others in Washington state’s King County Superior Court.

An appeals court issued a landmark ruling in a human rights lawsuit filed by a group of Belgian citizens against the national government and regional jurisdictions. The court mandated that the Belgian government must slash carbon emissions by at least 55 percent below 1990 levels by the year 2030.

Greenpeace Nordic and Young Friends of the Earth Norway challenged the Norwegian government's approval of three new North Sea oil fields.

Six young people from Portugal-with the younger one being 11 years old- brought a lawsuit against 32 European countries, marking the first instance in which so many national governments had to defend their climate policies collectively before a court. The young plaintiffs initiated the legal action in 2020, following several years of record-breaking heat in Portugal and devastating wildfires in 2017.

The Spanish Supreme Court dismissed the claim filed by the environmental associations GreenPeace España, Ecologistas en Acción-CODA and Oxfam Intermón against the Spanish government, confirming the alignment of its climate efforts with Spain’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Five farmers have petitioned a court to compel the Kenyan Government to limit the volume of greenhouse gas emissions in Kenya by 30%. The farmers claim that the emissions are posing a threat to the earth’s temperature, which is having negative side-effects in Kenya in the form of flooding, heat stress, forest fires, droughts, as well as disruption of food production and the supply of clean drinking water.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) was requested an advisory opinion on climate change (March 29). The UNGA in line with its resolution (A/77/L.58) initiated by the Republic of Vanuatu requested clarifications on the obligations of States with respect to climate change. For Vanuatu, similarly to other small island developing states, this is also a chance to spur transformative climate action, advance climate justice, and protect the environment for present and future generations.

An advisory opinion focuses on interpretation of the obligations in the Paris Agreement and UNFCCC and also on the human rights implications of climate change. Although ICJ advisory opinions have no binding force, given the strong reputation and legal weight of the Court, its opinion could possibly influence other courts and domestic litigation, would provide an authoritative statement on “the long-neglected matter of loss and damage” and their compensation and, finally, contribute to a more climate-sensitive global consciousness. See also International Court of Justice.