Section 15. Global Risks 2023

This Section presents key global risks and foreign policy trends according to the versions of several analytical centers, namely the analysts of the World Economic Forum, the consulting company Eurasia Group, and the Russian Economic News Agency PRIME.

15.1. Risks 2023 (WEF version)

The risk ranking in the WEF’s Global Risks Report 2023 draws on insights from experts across academia, civil society, government, and business all over the world.

The world has faced a set of risks that feel both wholly new and eerily familiar. First, it is a return of “older” risks – inflation, cost-of-living crises, trade wars, widespread social unrest, geopolitical confrontation and the spectre of nuclear warfare. Second, these are being amplified by comparatively new developments in the global risks landscape, including unsustainable levels of debt, a new era of low growth, low global investment and de-globalization, a decline in human development after decades of progress, rapid and unconstrained development of dual-use (civilian and military) technologies, and the growing pressure of climate change impacts and ambitions in an evershrinking window for mitigation.

The authors conclude that together, these are converging to shape a unique, uncertain and turbulent decade to come.

Cost of living dominates global risks in 2023–2025. Almost all respondents anticipated consistent volatility over the next two years due to aggravating crises destabilizing economies and causing harm to societies; more than half respondents predict persistent crises in the next decade leading to catastrophic consequences. The top risks – energy crisis, inflation and food supply crisis – represent the cost-of-living crisis dominating in the list of global threats over the next two years.

A global Cost-of-living crisis is already being felt. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the price of basic necessities – non-expendable items such as food and housing – were on the rise. Costs further increased in 2022, with inflationary pressures disproportionately hitting those that can least afford it. To curb domestic prices, around 30 countries introduced restrictions, including export bans, in food and energy last year, further driving up global inflation. Although global supply chains have partly adapted, with pressures significantly lower than the peak experienced in spring 2022, the FAO Price Index hit the highest level since the 1960s.

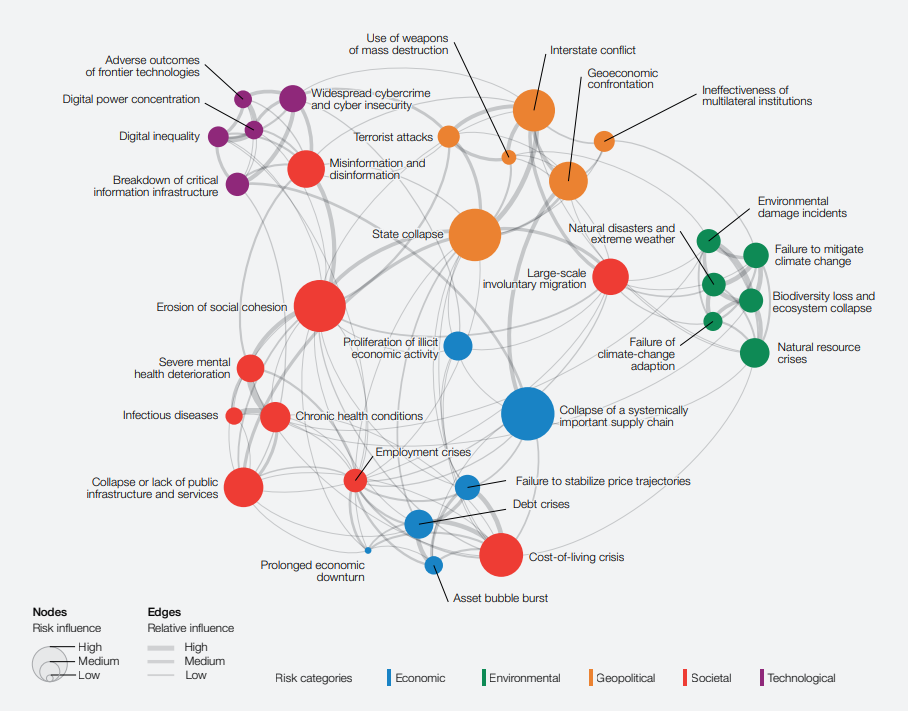

Risks map. Half in the top 10 risks over the next two years are environment-related risks from natural disasters and natural resource crises to failure to mitigate climate change and failure of climate-change adaptation. Another three risks are viewed as social ones – besides the cost-of-living crisis, these are the risks of societal polarization and large-scale involuntary migration.

Global risks ranked by severity over the short- and long-term

Geoeconomic confrontation. Geoeconomic confrontation, including sunctions and trade wars, was ranked the third-most severe risk over the next two years. A number of Asian countries, including China, Kazakhstan, and Japan considered it as the top risk (US as the third one). Economic policy is increasingly directed towards geopolitical goals: countries are seeking to build “self-sufficiency”, defending through tighter investment screening, data localization policies, visa bans and exclusion of companies from key markets.

Societal polarization. Polarization increases both between countries and people: societal polarization is among top 10 global risks over the short- (fifth rank) and long-term (seventh rank). Defined as the loss of social capital and fracturing of communities leading to declining social stability, individual and collective wellbeing and economic productivity, it is triggered by many other risks – including debt crises, inflation, a prolonged economic downturn and climate migration. A widening gap in values and equality is posing an existential challenge to both autocratic and democratic systems, as economic and social divides are translated into political ones.

“Climate action hiatus”. Severe polarization on key issues leads to deadlocked situations in governments hampering long-term decision making. This would contribute to stronger disagreements, especially in light of economic complexities and uncertainties in the next years.

It is characteristic that environmental risks account for half in top 10 short-term risks and take six positions, including first four rankings in top 10 risks over the next decade. Counteractions on global warming has stagnated: the combination of current economic, societal and geopolitical crises diverts attention and resources from the long-term risks and, eventually, the world may face the rising burden on natural and human ecosystems.

A failure to mitigate climate change is ranked as one of the most severe threats in the short term but is the global risk we are seen to be the least prepared for, with 70% of respondents rating existing measures to prevent or prepare for climate change as “ineffective” or “highly ineffective”.

Current energy crisis on the background of geopolitical conflicts should result in a turning point, encouraging energy-importing countries to invest in renewable energy sources. Yet the current situation have already limited – and in some cases reversed – progress on climate change mitigation, at least over the short term. For example, the EU spent at least €50 billion on new and expanded fossil-fuel infrastructure and supplies, and some countries restarted coal power stations.

Negotiations at the last climate conference failed, laying bare the difficulty of balancing short-term needs with longer-term ambitions. The stark reality of 600 million people in Africa without access to electricity illustrates the failure to deliver change to those who need it and the continued attraction of quick fossil-fuel powered solutions. A just transition that supports those set to lose from decarbonization is increasingly invoked by countries heavily dependent on fossil-fuel industries as a reason to slow down efforts.

This implies that the risks of a slower and more disorderly transition have now turned into reality. Climate change will also increasingly become a key migration driver and there are indications that it has already contributed to the emergence of terrorist groups and conflicts in Asia, the Middle East and Africa. As floods, heatwaves, droughts and other extreme weather events become more severe and frequent, a wider set of populations will be affected.

Global risks 2033: Tomorrow’s catastrophes. Shocks of recent years have reflected and accelerated an epochal change to the global order. Risks that are more severe in the short term are embedding structural changes to the economic and geopolitical landscape that will accelerate other global threats faced over the next 10 years.

Comparing the two-year and 10-year time frames provides a picture of areas of decreasing and increasing concerns. The last ones refer to environmental risks that have worsening scores over the course of the 10-year time frame. Large-scale involuntary migration caused mainly by climate change rises to fifth place.

The scores of multiple social risks are also worsening, including “Severe mental health deterioration”, “Collapse or lack of public infrastructure and services”, and “Chronic diseases and health conditions”. In contrast, economic risks such as “Failure to stabilize price trajectories”, “A prolonged economic downturn”, “Collapse of a systemically important industry or supply chain”, and “Asset bubble burst” are perceived to fall slightly in expected severity over the 10-year time frame. Respondents perceive the geopolitical risk of interstate conflict as decreasing in severity, with the risk of state collapse worsening.

Global risks landscape: an interconnections map

The authors identify five emerging risks clusters that that may become tomorrow’s catastrophes:

1. Natural ecosystems. Past the point of no return. Biodiversity is already declining faster than at any other point during human history. Over the next 10 years, the interplay between biodiversity loss, pollution, natural resource consumption, climate change and socioeconomic drivers will make for a dangerous mix. consequences. The consequences may include increased occurrence of zoonotic diseases, a fall in crop yields, growing water stress exacerbating potentially violent conflict, loss of livelihoods dependent on food systems, and ever more dramatic natural disasters.

2. Human health. Expanding sources of disease will combine with persistent disease burdens to entrench a growing health burden. A key implication is the resulting rise in disabilities, rather than deaths: people are living more years in poor health - medical advances have made it possible for people to live with multiple co-morbidities, but these remain complex and expensive to manage.

3. Human security. Growing mistrust and suspicion between global and regional powers has already led to the reprioritization of military expenditure and stagnation of non-proliferation mechanisms. Diffusion of military power to multiple countries and actors is driving the latest iteration of a global arms race.

4. Digital rights. The proliferation of data-collecting devices and datadependent AI technologies could open pathways to new forms of control over individual autonomy. As more data is collected and the power of emerging technologies increases over the next decade, individuals will be targeted and monitored by the public and private sector to an unprecedented degree, often without adequate anonymity or consent.

5. Economic stability.The rapid and widespread normalization of monetary policies, accompanied by a stronger US dollar and weaker risk sentiment, has already increased debt vulnerabilities that are likely to remain heightened for years. Larger emerging markets exhibiting a heightened risk of default include Argentina, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Tunisia, Pakistan and Turkey. Extended supply-driven inflation could drive more painful interest rate rises, even amidst a slowdown in growth, leading to a harder landing and more widespread debt distress. Even comparatively orderly fiscal consolidation is likely to impact spending on human capital and development, ultimately threatening the resilience of economies and societies in the face of the next global shock, whatever form it might take.

While ongoing polycrisis unfolds, the world stands at a crossroads, WEF concludes. The actions taken today will dictate our future risk landscape. In this context, defensive, fragmented and crisisoriented approaches are short-sighted and often perpetuate vicious cycles. Lack of preparedness for longer-term risks will destabilize the global risks landscape further, bringing ever tougher trade-offs for policy-makers and business leaders. Four principles for preparedness in this new era of polycrises can be outlined: 1) strengthening risk identification and foresight, 2) recalibrating the present value of “future” risks, 3) investing in multi-domain risk preparedness, and 4) strengthening preparedness and response cooperation.

15.2. Risks 2023 (Eurasia Group version)

The Eurasia Group consulting company launched its rating of ten global risks 2023. The world is through the pandemic. Renewables are becoming dirt cheap. The headwinds for human development will grow in 2023.

1. Rogue Russia. Russia will turn from global player into the world’s most dangerous rogue state, posing a serious security threat to Europe, the United States, and beyond.

2. Xi Jinping followed Mao: Xi emerged from China’s 20th Party Congress with a grip on power unrivaled since Mao Zedong

3. Weapons of mass disruption. New technologies will be a gift to autocrats bent on undermining democracy abroad and stifling dissent at home.

4. Inflation shockwaves. Rising interest rates and global recession will raise the risk of emerging-market crises.

5. Iran in a corner. The chance of regime collapse is low, but it's higher than at any point in the past four decades.

6. Energy crunch. Higher oil prices will also increase frictions between OPEC+ and the United States.

7. Arrested global development. Women and girls will suffer the most, losing hard-earned rights, opportunities, and security.

8. Divided states of America. The United States remains one of the most politically polarized and dysfunctional of the world’s advanced industrial democracies. Red-blue animosity creates the environment, which will become increasingly challenging for companies used to thinking of the United States as a coherent market with a predictable regulatory regime. There is also the continuing risk of political violence.

9. TikTok boom. Born between the mid-1990s and the early 2010s, Generation Z is the first with no experience of life without the internet. Digital devices and social media have connected its members across borders to create the first truly global generation. That makes them a new political and geopolitical force, especially in the United States and Europe.

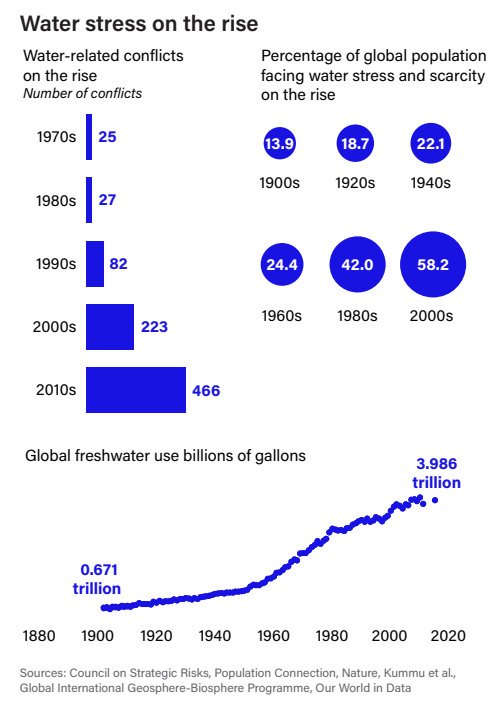

10. Water stress. In 2022, receding water levels exacerbated the food crisis in Africa, halted shipping and nuclear output in Europe, and led to factory shutdowns in China. Water scarcity also forced the United States to limit water releases in western states and triggered social unrest in Latin America, heightening tensions between corporations and communities. Forecasts for 2023 are worse. Water stress will become the new normal: River levels will fall to new lows, and two-thirds of companies globally will face substantial water risks to their operations or supply chains.

Within countries, the number of water-related conflicts, already up sharply since the 1980s, will reach new heights in 2023. The impact will be greatest in the Middle East and Africa, where water will act as a “trigger” in places where militias fight over the scarce resource, and as a “casualty” in places where militants destroy water pumps, tanks, and pipes. Water scarcity will also trigger refugee flows in the Middle East (Syria, Iraq, and Yemen), threaten economic prospects in North Africa (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia), and heighten food insecurity in the horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia) by driving food prices higher and forcing farmers to migrate.

US policymakers will have to choose between electricity generation, water releases, industrial production, and food production on the one hand, and water conservation on the other. More US farmers, who will suffer the most from water restrictions taking effect in 2023 , will be asked to forgo harvesting to help tackle water scarcity.

Europe will face different challenges. Norway may have to limit electricity exports to preserve hydropower for domestic use, exposing itself to legal challenges from the Netherlands and Germany. And sinking water levels in the Rhine and Po rivers will disrupt inland shipping and hamper broader economic activity in western Europe.

In Latin America, political decisions will push water-intensive industries such as beverage companies to move facilities from dry to water-rich regions. Local policymakers will follow Santiago de Chile's lead by rotating water cuts among customers, affecting the retail and hospitality industries.

Sources: Council on Strategic Risks, Population Connection, Nature,

Kummu et al., Global International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme,

Our World in Data

Eurasia Group's Top Risks for 2023

15.3. Economic News Agency “Prime”

Based on an expert survey, the Russian economic news agency “Prime” presented eight potential risks that the world will likely face in 2023. The global economic system is so ineffective now that it is difficult to predict when it crashes. This uncertainty will be the major risk to global economic stability in 2023.

Geopolitical conflicts. The armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine could reverse decades of economic gains. Other geopolitical tension points where new military conflicts could erupt and escalate into a global confrontation include China v. Taiwan, Israel v. Syria, the United States v. Mexico, Turkey v. Greece, South Korea v. North Korea, Serbia v. Kosovo, Azerbaijan v. Armenia, Moldova v. Transnistria, Africa countries (Somalia, Congo, South Sudan), South Asia (Afghanistan, Pakistan). For example, if confrontation around Taiwan turns into open military clashes, the global economy may risk collapse. The US would inevitably be involved in such conflict, and economic ties between the US and China (as well as China and the EU) would certainly be broken.

Political institutions crisis. The crisis of existing political institutions will worsen the global situation. And while Brexit was perceived by everyone as something extraordinary, today an increasing number of countries are declaring their strive for autonomy and, consequently, their desire to leave alliances that somehow restrict them. For example, the Organization of Turkic States, initially created as a trade union, is gradually beginning to talk about its own military doctrine. This is not yet a counterweight to global military alliances like NATO, but “they made a start”.

Inflation and global recession. Most economists conclude that the global economy will enter the hardest year. Today, economic growth in the leading industrial countries (primarily the US and Europe) has slowed down noticeably. However, it is believed that a large-scale recession could still be avoided through accelerated economic growth in China and India. But the latest data on China are also disappointing: a new round of coronavirus pandemic is on rise. Additionally, demand for Chinese and Indian goods has largely been driven by Western countries. Today, however, rising inflation in these countries is reducing demand, while internal demand and that from developing countries cannot compensate the resulting losses. This, in particular, has caused China’s budget gaps (currently, the budget deficit is about $1.1 trillion). One of scenarios in WB’s forecasts assumes an inflation rate up to 5%, which may result in recession and also in financial crises. Probably, defaults can be expected, first corporate defaults, and then sovereign ones (and here the Eurozone countries are particularly at risk). Ultimately, this will cause further stratification of the population, shrinking middle class, rising unemployment and poverty. Bankruptcies of both enterprises and individuals will be inevitable. Alas, bankruptcy may become a characteristic of 2023.

Markets. In December, the US Federal Reserve System (FRS) raised its median forecast for the federal funds rate from 4.6% to 5.1% by the end of 2023. However, the rate futures market still does not believe in such determination of the FRS and supposes that the US regulator will soften its position in 2023 to avoid ‘hard landing’ for the US economy. If this happens, a reassessment of rate expectations could trigger a strong decline in the equity market in the US and the world as a whole. This is another risk that could exacerbate the negative effects of recession.

Oil. Potentially large-scale rise in commodity prices as a result of reduced stock of energy and metals could put additional pressures on the global economy. This may cause stagflation. The main risk the oil market could face is a combination of recession in the EU, tight restrictions in China and stable situation in the US, where FRC will keep tight monetary policy to fight inflation. If the US makes some concessions to Iran and Venezuela, pressure on oil quotations both on Brent and on the Urals to Brent differential could increase sharply and would bring some exports close to operating margin. For Russia, analysts consider it as the additional devaluation factor and a reason to expand borrowings on the domestic debt market. Such situation probably persisting for more than two quarters will rise concerns about financial stability.

The gap of economic ties. The breach of economic ties will also contribute to worsened situation. And it is not just the situation between Russia and Western countries. The emerging tendency is that states prefer to build their own economic policy based on their own interests, often at the expense of cooperation and existing agreements. As is well-known from political economy, those countries that actively trade with each other, as a rule, do not fight. Now this principle is not followed. The war is not necessarily takes the form of an armed conflict, but can be also in the form of economic warfare and not less destructive. It is likely that in 2023 the confrontation between the largest exporting countries and the largest consuming countries will intensify - it will be a war of sanctions and embargoes, a price and currency war.

Climate. Climate variations, i.e. when summer drought alternates with extreme winter frosts may reduce grain yields and cause rise in prices/deficits. This will pose a threat to food security.

Humanitarian catastrophe. All the above mentioned could lead to humanitarian catastrophe. Thus, the failure to cooperate globally in the field of public health may result in a repeated pandemic like COVID-19, but a more serious one. A general decline in living standards will entail demographic problems. The glut of weapons will undoubtedly push up crime.

Source: Economic News Agency Prime