Section 12. Thematic reviews

12.1. Climate Change

State of Climate in 2022

According to WMO annual report, from mountain peaks to ocean depths, climate change continued its advance in 2022. Droughts, floods and heatwaves affected communities on every continent and cost many billions of dollars. Antarctic sea ice fell to its lowest extent on record and the melting of some European glaciers was, literally, off the charts.

The new WMO report is accompanied by a story map, which provides information for policy makers on how the climate change indicators are playing out, and which also shows how improved technology makes the transition to renewable energy cheaper and more accessible than ever.

Key messages

Temperature. The global mean temperature in 2022 was 1.15 [1.02–1.28] oC above the 1850–1900 average. The years 2015 to 2022 were the eight warmest in the 173-year instrumental record. The year 2022 was the fifth or sixth warmest year on record, despite ongoing La Nina conditions.

Global annual mean temperature anomalies with respect

to pre-industrial conditions (1850–1900)

for six global temperature data sets (1850–2022)

Near-surface temperature differences between 2022

and the 1991–2020 average.The map shows the median anomaly

calculated from six data sets

Greenhouse gases. Concentrations of the three main greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide – reached record highs in 2021, the latest year for which consolidated global values are available (1984-2021). The annual increase in methane concentration from 2020 to 2021 was the highest on record. Real-time data from specific locations show that levels of the three greenhouse gases continued to increase in 2022.

Glaciers. In the hydrological year 2021/2022, a set of reference glaciers with long-term observations experienced an average mass balance of -1.18 metres water equivalent (m w.e.). This loss is much larger than the average over the last decade. Six of the ten most negative mass balance years on record (1950-2022) occurred since 2015. The cumulative mass balance since 1970 amounts to more than -26 m w.e.

The European Alps smashed records for glacier melt due to a combination of little winter snow, an intrusion of Saharan dust in March 2022 and heatwaves between May and early September.

In Switzerland, 6% of the glacier ice volume was lost between 2021 and 2022 – and one third between 2001 and 2022. For the first time in history, no snow survived the summer melt season even at the very highest measurement sites and thus no accumulation of fresh ice occurred. Measurements on glaciers in High Mountain Asia, western North America, South America and parts of the Arctic also reveal substantial glacier mass losses. There were some mass gains in Iceland and Northern Norway associated with higher-than-average precipitation and a relatively cool summer.

According to the IPCC, globally the glaciers lost more than 6000 Gt of ice over the period 1993-2019. This represents an equivalent water volume of 75 lakes the size of Lac Leman (also known as Lake Geneva), the largest lake in Western Europe.

The Greenland Ice Sheet ended with a negative total mass balance for the 26th year in a row.

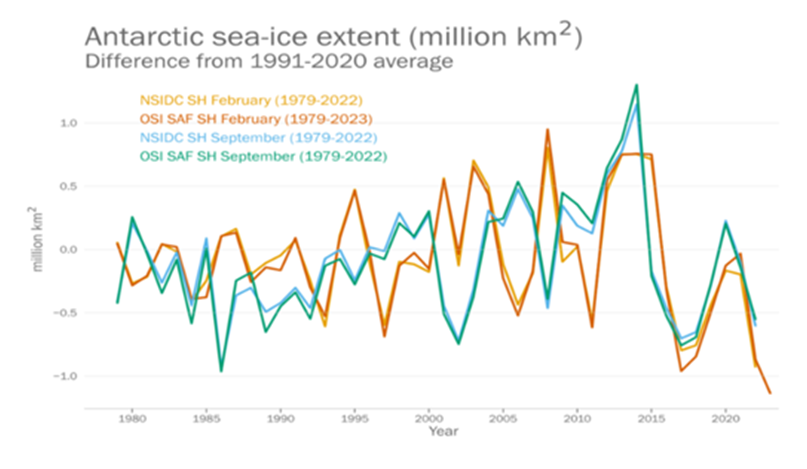

Sea ice in Antarctica dropped to 1.92 million km2 on February 25, 2022, the lowest level on record and almost 1 million km2 below the long-term (1991-2020) mean. For the rest of the year, it was continuously below average, with record lows in June and July.

Arctic sea ice in September at the end of the summer melt tied for the 11th lowest monthly minimum ice extent in the satellite record.

Ocean. Ocean heat content reached a new observed record high in 2022. Around 90% of the energy trapped in the climate system by greenhouse gases goes into the ocean, somewhat ameliorating even higher temperature increases but posing risks to marine ecosystems. Ocean warming rates have been particularly high in the past two decades. Despite continuing La Nina conditions, 58% of the ocean surface experienced at least one marine heatwave during 2022.

Sea level. Global mean sea level (GMSL) continued to rise in 2022, reaching a new record high for the satellite altimeter record (1993-2022). The rate of global mean sea level rise has doubled between the first decade of the satellite record (1993-2002, 2.27 mm/yr) and the last (2013-2022, 4.62 mm/yr).

For the period 2005-2019, total land ice loss from glaciers, Greenland, and Antarctica contributed 36% to the GMSL rise, and ocean warming (through thermal expansion) contributed 55%. Variations in land water storage contributed less than 10%.

Ocean acidification. CO2 reacts with seawater resulting in a decrease of pH referred to as ‘ocean acidification’. Ocean acidification threatens organisms and ecosystem services. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report concluded that “There is very high confidence that open ocean surface pH is now the lowest it has been for at least 26 [thousand years] and current rates of pH change are unprecedented since at least that time.”

The lowest level of Antarctic sea ice on record in February 2022

Socio-economic and environmental impacts

Drought. Drought gripped East Africa. Rainfall has been below-average in five consecutive wet seasons, the longest such sequence in 40 years. As of January 2023, it was estimated that over 20 million people faced acute food insecurity across the region, under the effects of the drought and other shocks.

Precipitation. Record breaking rain in July and August led to extensive flooding in Pakistan. There were over 1 700 deaths, and 33 million people were affected, while almost 8 million people were displaced. Total damage and economic losses were assessed at US$ 30 billion. July (181% above normal) and August (243% above normal) were each the wettest on record nationally.

Heatwaves. Record breaking heatwaves affected Europe during the summer. In some areas, extreme heat was coupled with exceptionally dry conditions. Deaths associated with the heat in Europe exceeded 15 000 in total across Spain, Germany, the UK, France, and Portugal.

China had its most extensive and long-lasting heatwave since national records began, extending from mid-June to the end of August and resulting in the hottest summer on record by a margin of more than 0.5 °C. It was also the second-driest summer on record.

Food insecurity. As of 2021, 2.3 billion people faced food insecurity, of which 924 million people faced severe food insecurity. As of October 2022, several countries in Africa and Asia (such as Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, and Afghanistan) and the Caribbean (Haiti) experienced starvation or death and required urgent humanitarian action. In these countries, the key drivers and aggravating factors for acute food insecurity were conflict/insecurity, economic shocks, political instability, displacement, dry conditions and cyclones.

Displacement. In Somalia, almost 1.2 million people became internally displaced by the catastrophic impacts of drought on pastoral and farming livelihoods and hunger during the year, of whom more than 60 000 people crossed into Ethiopia and Kenya during the same period. Concurrently, Somalia was hosting almost 35 000 refugees and asylum seekers in drought-affected areas. A further 512 000 internal displacements associated with drought were recorded in Ethiopia.

The flooding in Pakistan affected some 33 million people, including about 800 000 Afghan refugees hosted in affected districts. By October, around 8 million people have been internally displaced by the floods with some 585 000 sheltering in relief sites.

Environment. Climate change has important consequences for ecosystems and the environment. For example, a recent assessment focusing on the unique high-elevation area around the Tibetan Plateau, the largest storehouse of snow and ice outside the Arctic and Antarctic, found that global warming is causing the temperate zone to expand.

Climate change is also affecting recurring events in nature, such as when trees blossom, or birds migrate. For example, flowering of cherry blossom in Japan has been documented since AD 801 and has shifted to earlier dates since the late nineteenth century due to the effects of climate change and urban development. In 2021, the full flowering date was 26 March, the earliest recorded in over 1200 years. In 2022, the flowering date was 1 April.

Not all species in an ecosystem respond to the same climate influences or at the same rates. For example, spring arrival times of 117 European migratory bird species over five decades show increasing levels of mismatch to other spring events, such as leaf out and insect flight, which are important for bird survival. Such mismatches are likely to have contributed to population decline in some migrant species, particularly those wintering in sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: WMO

Climate Change Agreement

All five Central Asian countries ratified the Paris Agreement to address the climate change threats and take appropriate measures. As of February 2023, 195 members of UNFCCC are parties to the agreement. One of important aspects of the Paris Agreement is that developing countries also have to cut emissions along with developed countries. A massive shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewable sources will be needed for countries to comply with their obligations under the Paris Agreement and shift to a low-carbon and sustainable energy system. Today, fossil fuels account for 95% of total energy supply in the 5 countries of Central Asia. Analysis published by UNECE as part of its Carbon Neutrality Toolkit shows that under a business-as-usual scenario aiming at strengthening energy resilience to prevent blackouts and ensure reliable supply, the region would need to invest some $1.407 trillion between 2020 and 2050.

Climate Change Conference COP27

The United Nations Climate Change Conference COP27 brought together more than 45 000 delegates in Shark El Sheikh from 6 to 18 November.

COP27 resulted in countries delivering a package of decisions that reaffirmed their commitment to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The package also strengthened action by countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the inevitable impacts of climate change, as well as boosting the support of finance, technology and capacity building needed by developing countries.

Governments took the decision to establish new funding arrangements, as well as a dedicated fund, to assist developing countries in responding to loss and damage. Governments also agreed to establish a ‘transitional committee’ to make recommendations on how to operationalize both the new funding arrangements and the fund at COP28 next year. The first meeting of the transitional committee is expected to take place before the end of March 2023. Parties also agreed on the institutional arrangements to operationalize the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage, to catalyze technical assistance to developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.

COP27 saw significant progress on adaptation, with governments agreeing on the way to move forward on the Global Goal on Adaptation, which will conclude at COP28 and inform the first Global Stocktake, improving resilience amongst the most vulnerable. New pledges, totaling more than $230 million, were made to the Adaptation Fund at COP27. These pledges will help many more vulnerable communities adapt to climate change through concrete adaptation solutions. COP27 President Sameh Shoukry announced the Sharm el-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda, enhancing resilience for people living in the most climate-vulnerable communities by 2030. UN Climate Change’s Standing Committee on Finance was requested to prepare a report on doubling adaptation finance for consideration at COP28 next year.

The cover decision, known as the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, highlights that a global transformation to a low-carbon economy is expected to require investments of at least $4-6 trillion a year. Delivering such funding will require a swift and comprehensive transformation of the financial system and its structures and processes, engaging governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors and other financial actors. Serious concern was expressed that the goal of developed country Parties to mobilize jointly $100 billion per year by 2020 has not yet been met, with developed countries urged to meet the goal, and multilateral development banks and international financial institutions called on to mobilize climate finance.

At COP27, deliberations continued on setting a ‘new collective quantified goal on climate finance’ in 2024, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries.

The World Leaders Summit, held over two days during the first week of the conference, convened six high-level roundtable discussions. The discussions highlighted solutions – on themes including food security, vulnerable communities and just transition – to chart a path to overcome climate challenges and how to provide the finance, resources and tools to effectively deliver climate action at scale.

Young people in particular were given greater prominence at COP27, with UN Climate Change’s Executive Secretary promising to urge governments to not just listen to the solutions put forward by young people, but to incorporate those solutions in decision and policy making. Young people made their voices heard through the first-of-its-kind pavilion for children and youth, as well as the first-ever youth-led Climate Forum.

In parallel with the formal negotiations, the Global Climate Action space at COP27 provided a platform for governments, businesses and civil society to collaborate and showcase their real-world climate solutions. The UN Climate Change High-Level Champions held a two-week programme of more than 50 events. This included a number of major African-led initiatives to cut emissions and build climate resilience, and significant work on the mobilization of finance.

The highlights of the meeting included, among others, the launch of the first report of the High-Level Expert Group on the Net-Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities. The report slammed greenwashing – misleading the public to believe that a company or entity is doing more to protect the environment than it is – and provided roadmap to bring integrity to net-zero commitments by industry, financial institutions, cities and regions and to support a global, equitable transition to a sustainable future.

Other announcements at COP27:

• Countries launched a package of 25 new collaborative actions in five key areas: power, road transport, steel, hydrogen and agriculture.

• The Egyptian leadership also announced the Food and Agriculture for Sustainable Transformation initiative or FAST, to improve the quantity and quality of climate finance contributions to transform agriculture and food systems by 2030. This was the first COP to have a dedicated day for Agriculture, which contributes to a third of greenhouse emissions and should be a crucial part of the solution.

• UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres announced a $3.1 billion plan to ensure everyone on the planet is protected by early warning systems within the next five years.

• The UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Expert Group on Net-Zero Commitments published a report at COP27, serving as a how-to guide to ensure credible, accountable net-zero pledges by industry, financial institutions, cities and regions.

• The G7 and the V20 (‘the Vulnerable Twenty’) launched the Global Shield against Climate Risks, with new commitments of over $200 million as initial funding. Implementation is to start immediately.

• Announcing a total of $105.6 million in new funding, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, and the Walloon Region of Belgium, stressed the need for even more support for the Global Environment Facility funds targeting the immediate climate adaptation needs of low-lying and low-income states.

• Meanwhile, former US Vice-President and climate activist Al Gore, with the support of the UN Secretary-General, presented a new independent inventory of greenhouse gas emissions created by the Climate TRACE Coalition. The tool combines satellite data and artificial intelligence to show the facility-level emissions of over 70,000 sites around the world, including companies in China, the United States and India. This will allow leaders to identify the location and scope of carbon and methane emissions being released into the atmosphere.

• The new Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership, announced at the G20 Summit held in parallel with COP27, will mobilize $20 billion over the next three to five years to accelerate a just energy transition.

• Important progress was made on forest protection with the launch of the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership, which aims to unite action by governments, businesses and community leaders to halt forest loss and land degradation by 2030.

Central Asian countries at СОР27

Regional statement of the CA countries. During the 8th meeting of representatives of the ministries of foreign affairs and parliamentarians of Central Asian countries “Towards a regional coherence and cooperation of the countries of Central Asia in the field of climate policy, finance and implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)” at COP27, they announced a regional statement “Voice of Central Asia” on behalf of the governments of the Central Asian countries. The regional statement is to call the attention of the world community and international financing institutions to vulnerability of the region to climate change, emphasize the readiness of the Central Asian countries to strengthen international cooperation on the measures taken by the countries to adapt to and mitigate climate change and to strengthen regional cooperation on transboundary issues, as well as to attract climate financing in the region.

Position of NGOs and youth of the CA countries. Central Asian NGOs urged the governments of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, the UN, the EU, and the international and business communities to revise and significantly strengthen national and regional climate commitments. To prevent the climate crisis and negative consequences in Central Asia, emissions must be reduced by at least 30% by 2030 and reach zero balance by 2050. However, the commitments proposed by the CA countries are not sufficient. Arguments about the difficulties of achieving carbon neutrality, when examined in detail, turn out to be not so significant, but at the same time, the social and economic benefits of reducing emissions and adaptation for human health, employment and national economies are obvious! Representatives of youth networks in Central Asia — young climate and water experts, CALP graduates and members of the Working Group of the First in Central Asia RCOY CA made a separate statement.

Climate Change Reports

IPCC has completed two parts of its Sixth Assessment Report.

The second part of the report entitled “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation & Vulnerability” identifies and describes the risks associated with global climate change: these relate to changes in global ecosystems and to concrete effects on people in multiple spheres, from agriculture and health care to demography. One of the main conclusions is that adaptation still lags behind climate change. The overshoot of the 1.5°C limit will lead to irreversible transformations in Earth ecosystems, with the currently available adaptation tools turning out to be ineffective. In this context, the main task before humanity is to cut greenhouse gas emissions drastically.

The third part entitled “Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change” included detailed assessments of GHG emissions, pathways of their short-, middle- and long-term reduction, and detailed assessment of contributions by economic sectors to climate change. The report also addresses COVID-19, climate policies, sustainable development and international cooperation in the context of responses to climate change. By expert assessments, growth in anthropogenic emissions has persisted across all major groups of GHGs from 2010 to 2019, albeit at different rates. The annual growth was 1.3% and reached 59 ± 6.6 GtCO2-eq in 2019. The authors note that the COVID-19 pandemic could impede the achievement of SDGs, while taking away political and financial capacities from climate actions. Nevertheless, studies of previous post-shock periods have shown that these are crisis periods that can encourage new behaviors, weaken existing systems, and initiate rapid reforms. Limiting warming to 2°C relative to the pre-industrial level by the end of the century is possible by authors’ opinion only if enough stringent restrictive measures are observed. To this end, for instance, energy generation from oil must be reduced by 2030 by 10% relative to 2019 and by 2050 by 40%; that from gas, by 15% and 30%, respectively. Around the 2070s it is expected to reach global net zero CO2 emissions. This will require deep decarbonization of all economic sectors that will be facilitated by a wide circle of decision makers. Governments and public institutions may contribute to climate mitigation through a legal framework for recommended climate policy measures and economic support of these measures and diversification of their implementers. The legal framework should include establishment of land rights, state support to new technologies, adoption of standards for transport vehicles and emission regulation, and assessment of ecosystem services.

10 New Insights in Climate Science 2022 are based on the assessment of more than 60 leading world experts. This year the authors reveal the complexities of the interactions between climate change and other risks, such as conflicts, pandemics, food crises and underlying development challenges.

1. Questioning the myth of endless adaptation: Limits to adaptation are being breached already in different places across the world. Climate adaptation will become increasingly difficult as we approach 1.5°C or 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures. Existing adaptation efforts are falling short of adequately reducing risks from past, current and future climate change, leaving the most vulnerable particularly exposed to climate impacts. Adaptation cannot substitute for ambitious mitigation efforts. Even effective adaptation will not avoid all losses and damages, and new limits to adaptation can emerge in the shape of conflicts, pandemics and pre-existing development challenges. Deep and swift mitigation is critical to avoid widespread breaching of adaptation limits.

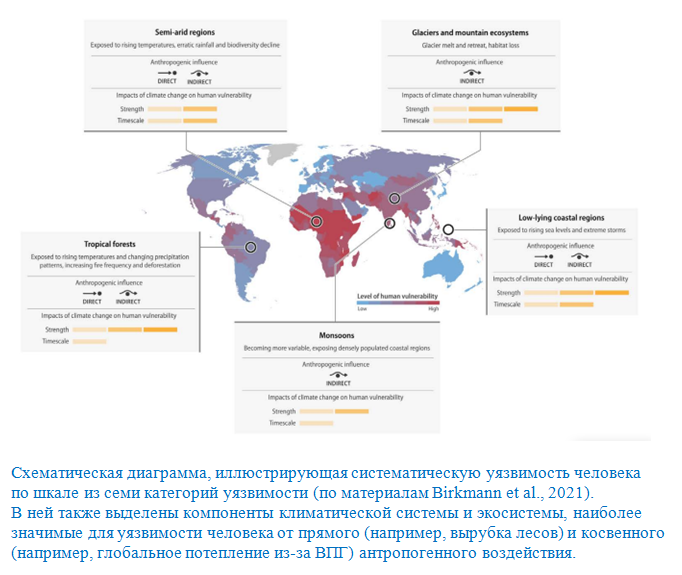

2. Vulnerability hotspots cluster in ‘regions at risk’: Approximately 1.6 billion people live in vulnerability hotspots, a number projected to double by 2050. Climate-driven hazard mortality is 15 times higher in hotspot countries than in the least-vulnerable countries. Vulnerability – the susceptibility to be adversely affected by climate-driven hazards – is a product of structural inequality in human–environmental systems. It clusters in major “regions at risk”: in parts of Central America, Asia and the Middle East, and in Africa across the Sahel, Central and East Africa. Communities in these regions at risk are increasingly exposed to climate change and climate-related hazards, where resilience (physical, ecological and socioeconomic) decreases with worsening levels of inequality, state fragility and poverty. Habitat degradation is putting many ecosystems in Arabian Peninsula and CA at high risk of structural and dynamic change, reducing their climate mitigation capability. It also decreases the ecosystem services and resources those habitats can provide, threatening the adaptive capacity of marginalized groups.

3. New threats on the horizon from climate–health interactions: Compounding and cascading risks due to climate change are adversely impacting human, animal and environmental health. Heat-related deaths, wildfires bringing physical and mental health impacts, and increasing risks of outbreaks of infectious diseases are all related to climate change.

4. Climate mobility: from evidence to anticipatory action: Involuntary migration and displacement will increasingly occur due to climate change-related slow-onset impacts and the rising frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. Climate change and related impacts can also result in many people losing their capacity to adapt by moving away. Thus, anticipatory humanitarian actions to assist climate-related mobility and minimize displacement are critical.

5. Human security requires climate security: Climate change exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in human security (caused by governance and socioeconomic conditions), which can lead to violent conflict. Effective and timely mitigation and adaptation strategies are required to strengthen human security and, by extension, national security. These must be pursued in parallel with concerted efforts to provide for human security to reduce the risks of increasing violent conflict and promote peace.

6. Sustainable land use is essential to meeting climate targets: Agricultural intensification that is long-term sustainable is preferable to further expansion into natural areas, when proper policies are in place to limit increased land conversion. Efforts to increase food production through enhanced yields and system integration while minimizing adverse ecological impacts can likewise do much to further food security. However, the higher the degree of warming, the less likely the current assumptions about the capacity of land systems to deliver these co-benefits will apply.

7. Private sustainable finance practices are failing to catalyze deep transitions needed to meet climate targets. The large majority of today’s sustainable finance practices are designed to fit into the financial sector’s existing business models rather than to allocate capital in ways that would provide the most impact on combating climate change.

8. Loss and Damage: the urgent planetary imperative: Losses and damages are already happening and will increase significantly on current trajectories, but rapid mitigation and effective adaptation can still prevent many of these. A coordinated, global policy response to losses and damages is urgently needed.

9. Inclusive decision-making for climate-resilient development: Being inclusive and empowering in all forms of decision-making has been shown to lead to better and more just climate outcomes.

10. Breaking down structural barriers: multidimensional structural barriers arising from the current resource-intensive economy and its vested interests in maintaining the status quo are inhibiting transformational change. Integration of justice and equality aspects in global agreements, decision making processes, and production and consumption mechanisms, de-risking of decarbonisation investments and radical revision of how we track progress will strengthen climate actions and remove the deep-rooted inequalities.

Source: 10insightsclimate.science

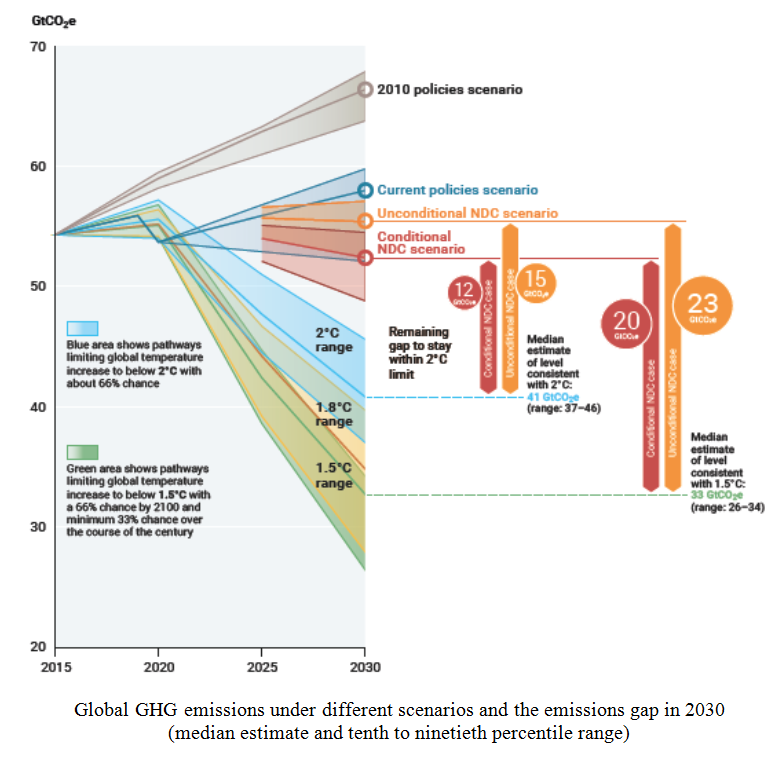

UNEP published the 13th edition of the Emissions Gap Report for 2022 entitled “The Closing Window – Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies”. The Report finds that the international community is falling far short of the Paris goals, with no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place. Only an urgent system-wide transformation can avoid climate disaster.

1. Testimony to inadequate action on the climate crisis and the need for transformation. Countries’ new and updated NDCs submitted since COP 26 reduce projected GHG emissions in 2030 by only 0.5 gigatons of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e), compared with emissions projections based on mitigation pledges at the time of COP 26. To get on track for limiting global warming to 1.5°C, global annual GHG emissions must be reduced by 45 per cent compared with emissions projections under policies currently in place in just eight years, and they must continue to decline rapidly after 2030, to avoid exhausting the limited remaining atmospheric carbon budget.

2. Global GHG emissions could set a new record in 2021. Global GHG emissions for 2021, excluding LULUCF , are preliminarily estimated at 52.8 GtCO2e, a slight increase compared to 2019, suggesting that total global GHG emissions in 2021 will be similar to or even break the record 2019 levels.

3. GHG emissions are highly uneven across regions, countries and households. Per capita emissions vary greatly across countries. World average per capita GHG emissions (including LULUCF) were 6.3 tCO2e in 2020. India remains far below the world average at 2.4 tCO2e.

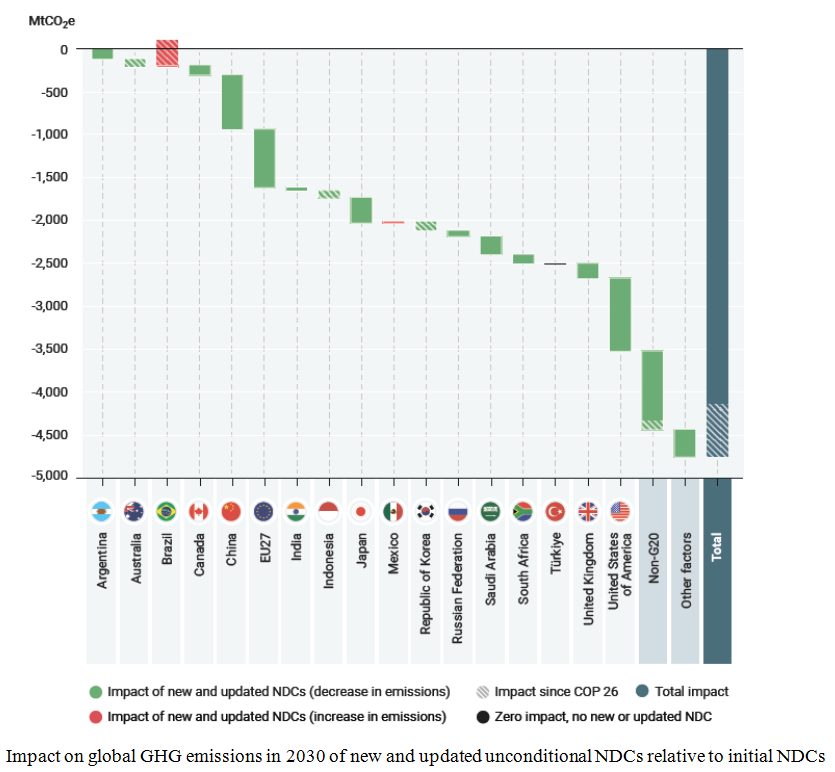

4. Despite the call for countries to “revisit and strengthen” their 2030 targets, progress since COP 26 is highly inadequate.

NDCs submitted since COP26 take only 0.5 GtCO2e, less than one per cent, off projected global emissions in 2030. Between 1 January 2020 and 23 September 2022, 166 parties representing around 91 per cent of global GHG emissions had submitted new or updated NDCs, up from 152 parties as of COP 26.

5. G20 members are far behind in delivering on their mitigation commitments for 2030, causing an implementation gap. Most of the G20 members have just started the implementation of policies and actions to meet their new targets. The G20 members would collectively fall short of achieving their NDCs by 2030 if stronger measures are not taken.

6. Globally, the NDCs are highly insufficient, and the emissions gap remains high. Current commitments by countries as expressed in their unconditional and conditional NDCs for 2030 are estimated to reduce global emissions by 5 and 10 per cent respectively, compared with current policies and assuming that they are fully implemented. To get on track for limiting global warming to below 2.0°C and 1.5°C, global GHG emissions must be reduced by 30 and 45 per cent respectively, compared with current policy projections.

7. Without additional action, current policies lead to global warming of 2.8°C. Implementation of unconditional and conditional NDC scenarios reduce this to 2.6°C and 2.4°C, respectively. A continuation of the level of climate change mitigation effort implied by current unconditional NDCs is estimated to limit warming over the twenty-first century to about 2.6°C (range: 1.9–3.1°C) with a 66 per cent chance, and warming is expected to increase further after 2100 as CO2 emissions are not yet projected to reach net-zero levels.

8. The credibility and feasibility of the net-zero emission pledges remains very uncertain.

9. Wide-ranging, large-scale, rapid and systemic transformation is now essential to achieve the temperature goal of the Paris Agreementя. The following broad portfolio of key actions to initiate and advance the transformation must be undertaken, tailored to the specific context of each of the four sectors: (1) avoiding lock-in of new fossil fuel intensive infrastructure; (2) enabling the transition by further advancing zerocarbon technologies, market structures and plans for a just transformation; (3) applying zero-emissions technologies and promoting behavioural change to sustain and deepen reductions to reach zero emissions.

10. The food system accounts for one third of all emissions, and must make a large reduction. The largest contribution stems from agricultural production (7.1 GtCO2e, 39%) including the production of inputs such as fertilizers, followed by changes in land use (5.7 GtCO2e, 32%), and supply chain activities (5.2 GtCO2e, 29%). The latter includes retail, transport, consumption, fuel production, waste management, industrial processes and packaging. Projections indicate that food system emissions could reach ca 30 GtCO2e/year by 2050.

11. Realignment of the financial system is a critical enabler of the transformations needed. A global transformation to a low-carbon economy is expected to require investments of at least $4–6 trillion a year, a relatively small (1.5–2%) share of total financial assets managed, but significant (20–28%) in terms of the additional annual resources to be allocated. Delivering such funding will require a transformation of the financial system and its structures and processes, engaging governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors and other financial actors.

The 6th Yearbook of Global Climate Action was published in 2022. It outlines what is needed to accelerate sectoral systems transformation, features case studies of real-world climate action projects, highlights some key global climate action topics – particularly regionalization and accountability. It also highlights what needs to be achieved in 2023, particularly with regard to the Global Stocktake and the work being done on implementing the improved Marrakech Partnership.

Significant and Major Events

The UN Security Council held two “Arria-formula” meetings: (1) at ministerial level on climate finance as a means to build and sustain peace in conflict, post-conflict and crisis situations (9 March, UAE); (2) on the theme “Climate, Peace and Security: Opportunities for the UN Peace and Security Architecture” (29 November, New York) (see Security Council).

Third UN Climate and SDG Synergies Conference brought together more than 2,000 participants (July 20-21, Tokyo, hybrid format). It generated an impressive range of potential solutions and proposals for how to better integrate efforts to tackle these interlinked global crises and accelerate action to address the climate emergency and recent reversals in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

Global trends in climate change litigation in 2022

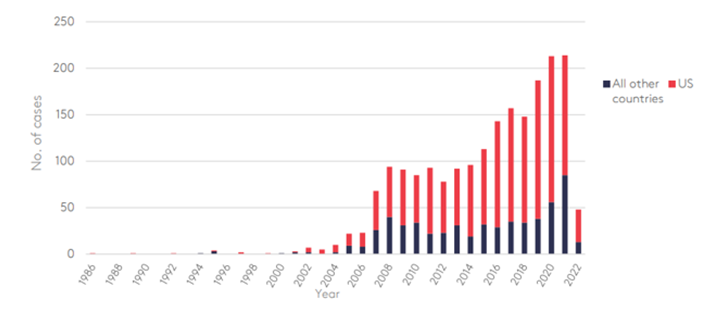

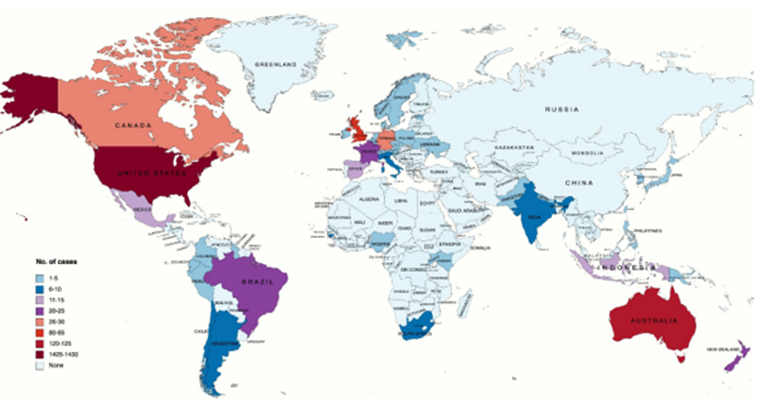

2,002 cases of climate change litigation were identified from around the world, as of May 2022 (see Figure below). Of these, 1,426 were filed before courts in the United States, while the remaining 576 were filed before courts in 43 other countries and 15 international or regional courts and tribunals. Outside the US, Australia (124 cases), the UK (83) and the EU (60) remain the jurisdictions with the highest volume of cases.

Data from the past 12 months confirms that litigation continues to expand as an avenue for action on climate change. While the number of cases in the US was lower than in previous years – likely down to the change in federal government – 2021 saw the highest number of recorded cases outside the US.

Globally, the cumulative number of climate change-related litigation cases has more than doubled since 2015. Just over 800 cases were filed between 1986 and 2014, and over 1,200 cases have been filed in the last eight years, bringing the total in the databases to 2,002. Roughly one-quarter of these were filed between 2020 and 2022.

Source: Setzer J. and Higham С. (2022) Global trends in climate change litigation: 2022 snapshot. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law

Remarkable climate change litigation cases in 2022

In Australia a court moved to block an $8.4bn coal mine development in Queensland on human rights grounds in a landmark case that highlights the mounting legal challenges to fossil fuel extraction around the world. The court said that the project would have infringed on the rights of First Nations people in Queensland because of its climate impact.

On November 16, the first hearing took place in Germany to force carmaker BMW to "drastically reduce" the CO2 emissions of its vehicles, and that by October 31, 2030, BMW must build new passenger cars that emit a maximum of 604 million tons of CO2, or prove greenhouse gas neutrality for any CO2 emissions beyond this.

Greta Thunberg jointly with more than 600 children and young adults in Aurora eco-movement has filed a lawsuit against the Swedish state for climate inaction. The activists claim the Swedish state to acknowledge its climate policy be flawed.

Greenpeace filed a case before the court against the UK Government for potential disruption of climate goals. The green lobbyists try to stop issuing more than 100 new licenses for oil and gas exploration in the North Sea. They believe that licensing of fuel mining companies will be a real catastrophe that undercuts any hope for the achievement of the Paris Agreement. This will make it impossible to limit the global temperature growth to 1.5°C. British authorities refused to comment the legal challenge, insisting on the need to increase national energy security through development of local energy sources.

The Fridays for Future movement activists filed a climate change litigation case against the Government of Russia for the first time. The litigants claimed the Government to annul the statement in the Presidential decree on cutting of greenhouse gas emissions that says by 2030 the GHG emissions shall be reduced to 70% relative to 1990. While the activists claim for the emissions reductions down to 31%.

American teenagers v. United States climate change lawsuit. The Juliana v. the United States continued in 2022. Twenty one American teenagers filed a class action lawsuit against the US Government. Their complaint asserts that, through the government's affirmative actions that cause climate change, it has violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, as well as failed to protect essential public trust resource. State of things: the youth plaintiffs continue awaiting a ruling on their Motion for Leave to File a Second Amended Complaint, the favorable decision on which would enable them to proceed to trial.