Section 15. Global Risks 2022

This Section presents key global risks and foreign policy trends according to the versions of several analytical centers, namely the analysts of the World Economic Forum, the consulting company Eurasia Group, and the American private geopolitics publisher and consultancy Stratfor.

15.1. Risks 2022 (World Economic Forum)

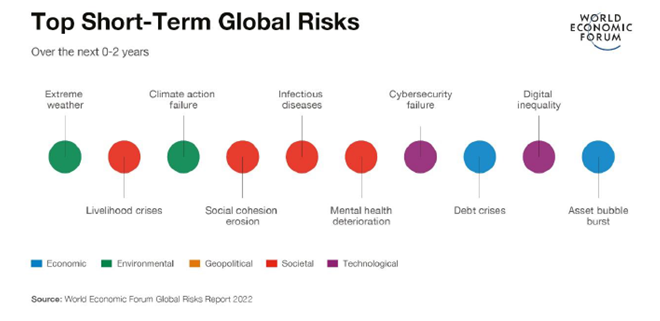

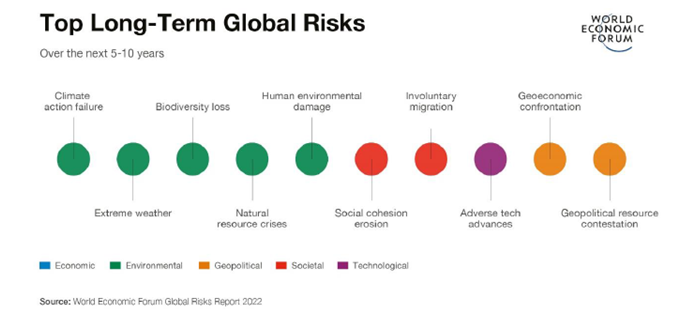

According to the WEF’s Global Risks Report 2022, the main risks on a global scale are related to climate threats. “Climate action failure”, “extreme weather”, and “biodiversity loss” will be the most severe risks over the next 10 years. Technological risks—such as “digital inequality” and “cybersecurity failure”—are other critical short- and medium-term threats to the world. “Social cohesion erosion”, “livelihood crises” and “mental health deterioration” are also included in the group of short-term risks.

Most respondents expect the next three years to be characterized by either consistent volatility and multiple surprises or fractured trajectories of global economic recovery. Just 11% believe the global recovery will accelerate by 2024, and 89% consider the near-term outlook to be volatile. 84% of respondents are fully worried about the outlook for the world. Experts are calling on world leaders to develop a policy to deal with global risks, with a clear agenda for the coming years. Growing societal concerns and tension hamper more equal and rapid recovery of economy. In this context, the world leaders must unite and adopt a coordinated multilateral approach to overcome persistent global challenges.

Climate (in-)action

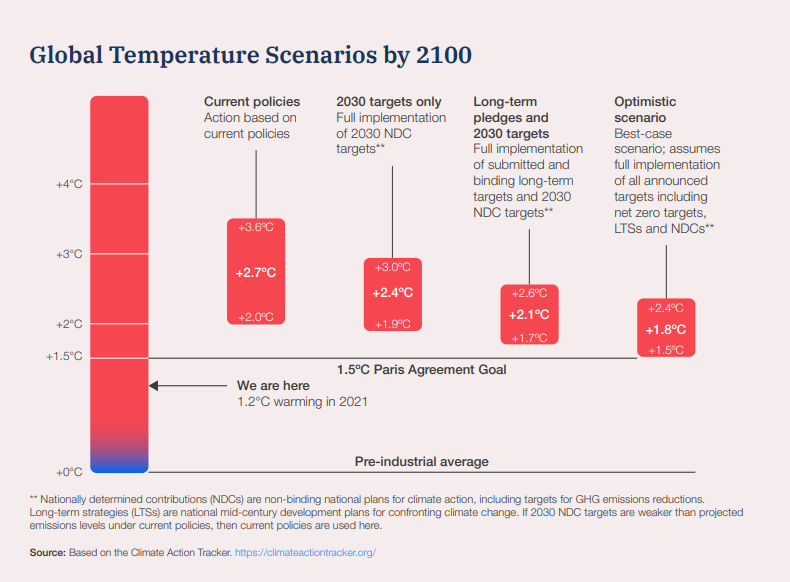

The latest nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to decarbonization made at the 2021 COP26 still fall short of the 1.5°C goal set out in the Paris Climate Agreement. The current trajectory is expected to steer the world towards a 2.4°C warming, with only the most optimistic of scenarios holding it to 1.8°C.

Without stronger action, global capacity to mitigate and adapt will be diminished, eventually leading to a “too little, too late” situation and ultimately a “hot house world scenario” with runaway climate change that makes the world all but uninhabitable. The world will face high costs if we collectively fail to achieve the net zero goal by 2050. Complete climate inaction will lead to losses projected to be between 4% and 18% of global GDP with different impacts across regions.

The transition to net zero—the state in which greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted into the atmosphere are balanced by their removal from the atmosphere—could be as transformative for economies and societies as past industrial revolutions. However, the complexities of the technological, economic and societal changes needed for decarbonization, coupled with the slow and insufficient nature of current commitments, will inevitably lead to varying degrees of disorderliness.

As climate change intensifies and some economies recover more quickly than others from COVID-19, a disorderly transition could bifurcate societies and drive countries further apart, and a too slow transition will only beget damage and disruption across multiple dimensions over the longer term. Within countries, the disruptive potential of the transition could be amplified by disconnects between governments, businesses and households with respect to policy commitments, financial incentives, regulations and immediate needs. A sustained lack of coordination between countries would likely have profound geopolitical implications, with rising friction between strong decarbonization advocates and those who oppose quick strong action by using tactics such as stalling climate action or greenwashing .

Based on the findings from this year’s survey, WEF identified five lessons that governments, businesses, and decision-makers should utilize in order to build resilience and prepare for future challenges:

1. Build a holistic mitigation framework: Rather than focusing on specific risks, it’s helpful to identify the big-picture worst-case scenario and work back from there. Build holistic systems that protect against adverse outcomes.

2. Consider the entire ecosystem: Examine third-party services and external assets, and analyze the broader ecosystem in which you operate.

3. Embrace diversity in resilience strategies: Not all strategies will work across the board. Complex problems will require nuanced efforts. Adaptability is key.

4. Connect resilience efforts with other goals: Many resilience efforts could benefit multiple aspects of society. For instance, efficient supply chains could strengthen communities and contribute to environmental goals.

5. Think of resilience as a journey, not a destination: Remaining agile and vigilant is vital when building out resilience programs, as these efforts are new and require reflection in order to improve.

The next few years will be riddled with complex challenges, and our best chance at mitigating these global risks is through increased collaboration and consistent reassessment.

The Global Risks Report 2022 is downloadable

15.2. Risks 2022 (Eurasia Group)

The Eurasia Group consulting company presented the top 10 global risks of 2022 A domestic focus for both the U.S. and Chinese governments lowers the odds of a big international conflict in 2022, but it leaves less potential leadership and coordination to respond to emerging crises.

1. No zero COVID. China, the primary engine for global growth, will face highly transmissible COVID-19 variants. China’s policy will fail to contain infections, lead to larger outbreaks, and require more severe lockdowns. That means greater economic disruptions, lower consumption, and a more dissatisfied population at odds with the triumphalist “China defeated COVID” of the state-run media.

2. Technopolar world. Experts believe the physical world is a mess because no countries are willing or able to provide global leadership; digital space is even more poorly governed.

3. U.S. midterms. This year's vote will not itself provoke a crisis, but it represents a historic tipping point.

4. China at home. Xi's policies increase the risk of stagnation at a time when the Chinese economy is on weak footing.

5. Russia. A buildup of Russian troops near Ukraine has opened a broader confrontation over Europe’s security architecture. President Vladimir Putin could send in troops and annex the occupied Donbas, but his current demand is for major NATO security concessions and a promise of no further eastward expansion.

6. Iran. The Biden administration failed to prepare for the possibility that Iran would not be interested in reviving the nuclear deal.

7. Two steps greener, one step back. In 2022, continued upward pressure on energy costs will force governments to favor policies that lower energy costs but delay climate action. Rising energy prices will raise anxiety levels for both voters and elected officials—even as climate pressures on government increase.

8. Empty lands. The United States is no longer interested in playing the role of global policeman, leading already to distraction from the situation in Afghanistan. Civil wars will create new risks in Yemen, Myanmar and Ethiopia. Venezuela and Haiti risk growing refugee crises. Destabilization of whole regions naturally threats both countries themselves and businesses operating there.

9. Corporates losing the culture wars. Multinational corporations (MNCs) with operations in the West and China will face a “two-way risk” despite record profits. Consumers and employees, empowered by “cancel culture” and enabled by social media, will make new demands on multinational corporations and the governments that regulate them. Many people in developed countries are not willing to tolerate the exploitation of people in developing countries. At the same time, China tends to more sovereignization and fights against political and economic pressures from MNCs.

10. Turkey. Erdogan's foreign policy positions will remain combative to distract voters from the economic crisis.

The Eurasia Group's Top Risks for 2022 is downloadable

15.3. Risks 2022 (Stratfor)

The Stratfor analysts revealed the annual forecast for 2022. As the world enters the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economic recovery that began in 2021 is likely to continue in 2022 but to slow down due to factors including pervasively high energy and food prices, persistent supply chain bottlenecks and tightening credit conditions.

The analysts believe that the pandemic will continue to create economic uncertainty and take lives around the world, vaccination rates will remain uneven between rich and poor countries, and new variants of the virus could present additional challenges to governments. It is expected that most of the world is to adopt a "live-with-COVID" strategy that seeks to keep economies as open as possible and to avoid the recession-provoking policies of 2020 and parts of 2021.

Core geopolitical fault lines of 2021 will continue into 2022. Tensions between Washington and Beijing are likely to persist, as the Biden administration will maintain high tariffs on Chinese products and may recalibrate some of them to focus on strategic industries, like high tech. While the White House will keep communication channels open with the Kremlin, issues ranging from Ukraine to divergences over cybersecurity governance will prevent the U.S. and Russia from reaching significant agreements or sanctions relief. And while the European Union will seek to preserve its cordial ties with the Biden administration, internal divergences between member states will prevent the bloc from fully aligning itself with the United States and adopting more hawkish positions on either Beijing or Moscow.

For the developing world, 2022 will be a year of challenges and opportunities. In India, the softening of lockdown measures is likely to result in a robust but uneven recovery, as the pandemic exacerbated the country's inequality issues. In Turkey, unorthodox monetary decisions and a nationalist foreign policy will create the twin risks of a financial crisis and military clashes with foreign powers. In Afghanistan, the Taliban will seek to stabilize the country's internal security situation in an effort to attract foreign aid, but domestic insurgencies will continue.

Central Asia Adjusts to the Taliban

Threats to security and stability in Central Asia and the rise of the Taliban will lead the states to continue their largely conciliatory stance toward Kabul. Concerns over drought, electricity shortages, a slow economic recovery and the continued spread of COVID-19 due to high vaccine hesitancy will push Central Asian governments to seek improved ties with the Taliban government in Afghanistan out of fear that the humanitarian crisis in the country could exacerbate their own social and economic problems and make them targets for groups sympathetic to the Taliban. The threat of refugee flows from Afghanistan and their possible infiltration by extremists will also prompt the Central Asian governments to avoid confrontation with the Taliban despite their deep ideological disagreements. Tajikistan, the country most opposed to the Taliban leadership, will increasingly rely on Russian and Chinese support to deter incursion or destabilization by Taliban-aligned groups or provocations by the Taliban.

The threat of extremist destabilization efforts may also prompt other states in the region to seek formal agreements to expand their security and economic relations with Moscow and Beijing, suggesting an increase in strategic competition between the two is on the way. Separately, despite the increased threat to domestic stability due to tensions on its southern border, Uzbekistan will not rejoin the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization security alliance it left in 2012, in part due to concerns about losing strategic autonomy amid deepening ties with China. Russia will continue accepting large numbers of migrant laborers from the region despite the increased security concerns over such migration amid the rise of the Taliban as part of Moscow's strategy to combat extremist sentiments in Central Asia by allowing many of those who would be otherwise vulnerable to radicalization efforts amid low wages and unemployment to leave.

The Stratfor’s annual report is downloadable