Section 12. Thematic reviews

12.4 COVID-19, Water and the Environment: Risks and Opportunities

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the value of water and its connections to human health and the environment, but it has also highlighted longstanding water management and environmental governance deficiencies. For example, while hand washing is one of the most effective ways for preventing the spread of COVID-19 and other communicable diseases, 40% of the global population – three billion people – live without soap and water available at home. In the face of COVID-19, they are among the most vulnerable and most at risk of being left behind.

While this global health crisis has raised new water and environment related challenges for national governments, local communities and the private sector, it could also be an important turning point for addressing longstanding challenges, including the failure to provide safe and affordable water and sanitation for all. The surge in interest, along with potentially massive investments by the business community and government to mitigate risks and help ailing economies, could provide a rare opportunity for more effective and equitable water and environmental policies and management.

This review gathers insights from across the globe to highlight some of the most pressing questions for decision makers, practitioners and citizens alike.

Water, sanitation and hygiene: World Leaders' Call to Action on COVID-19

Heads of State, Government, and leaders from United Nations agencies, International Financial Institutions, civil society, private sector and research and learning are mobilizing around a call for the prioritization of water, sanitation and hygiene in the response to COVID-19. Their joint statement:

Until there is a vaccine or treatment for COVID-19, there is no better cure than prevention.

Water, sanitation and hand hygiene, together with physical distancing, are central to preventing the spread of COVID-19, and a first line of defence against this serious threat to lives and health systems. Handwashing with water and soap kills the virus but requires access to running water in sufficient quantities.

Our response plans – at national, regional and global levels – must therefore prioritize water, sanitation and hygiene services.

Leaders that recognize the role of water, sanitation and hygiene in preventing the spread of COVID-19, will save lives. Leaders that prioritize international collaboration and support, will save lives. We are only as healthy as the most vulnerable members of society, no matter in which country they are.

Hence, we call on all national, regional and global leaders to join us in:

Making water, sanitation and hygiene available to everyone, eliminating inequalities and leaving no one behind, taking care of those who are most vulnerable to COVID-19. This includes the elderly, people with disabilities, women and girls, and those living in precarious situations, such as in informal settlements, refugee camps, detention centres, homeless people, as well as those people whose livelihoods are limited or destroyed by measures put in place to stop the spread of the virus, and women who shoulder the vast majority of unpaid care work in crisis. These measures are critical, not just to protect these vulnerable populations from COVID-19, but also to prevent other infectious diseases that can spread when water, sanitation and hygiene services are disrupted.

Working collaboratively with all stakeholders in a coordinated manner to improve water and sanitation services, as each actor, whether public, private, donor or civil society has something to offer to protect populations from COVID-19. Coordinated action is more effective, including urgent immediate action to establish handwashing facilities within health care facilities and at entrance points to public or private commercial buildings and public transport facilities, Partnerships such as Sanitation and Water for All are key platforms for national, regional and international cooperation and exchange of experiences.

Ensuring that water and sanitation systems are resilient and sustainable in order to protect people’s health and support national health systems. Service providers for water, sanitation and hygiene including utilities and informal providers will have difficulties to maintain or expand services at a time of reduced financial flows restricted movement. This is both a short-term and a long-term requirement to save lives. Undisrupted global supply chains, including movement of goods and production capacity, for water, sanitation and hygiene commodities and services must be maintained at all costs. Water, sanitation and hygiene workers must also be grated sufficient protection to be able to provide us with such services without disruption.

Prioritizing the mobilization of finance to support countries in their response to this crisis. Any financing directed at supporting emergency interventions must have long-term solutions already in mind. Access to water, sanitation and hygiene must be affordable to all, and this may require additional funding to support service providers and help those who cannot afford it. Funding envelopes need to be maintained with no diversion away from the commitments and priorities set for the water, sanitation and hygiene sector. This includes avoiding any shifts in domestic funding allocations that support WASH services and sustained support by international donors for on-going water, sanitation and hygiene humanitarian responses, and broader Grand Bargain commitments.

Delivering accurate information in a transparent manner. Consistent and rational messaging based on scientific advice that is accessible to everyone will help people to understand the threat and enable everyone to act accordingly.

COVID-19 is not the first and will not be the last epidemic that countries will face. Resilience to future crises depends on actions taken now, as well as on policies, institutions and capacity put in place during normal times. Let us ensure this threat is not a missed opportunity to achieve our vision of universal access to water, sanitation and hygiene.

As leaders, this is our chance to save lives.

Join the movement #GlobalCall4Water

COVID-19: the role of the Water Convention and the Protocol on Water and Health

The Water Convention and the Protocol on Water and Health jointly serviced by WHO-Europe and UNECE help countries by promoting the availability of safe water for all within countries and across borders and sectors.

Water Convention: Supporting recovery and preparedness

The timely and sufficient availability of water of adequate quality is a prerequisite for the provision of safe water, sanitation and adequate hygiene and for tackling possible impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, including poverty, economic downturn, food and energy insecurity and political instability. 60 percent of global freshwater flow comes from transboundary basins. The Water Convention provides a unique global legal and intergovernmental framework for peaceful and cooperative management of transboundary water resources and allows preventing potential tensions between countries and avoiding adverse transboundary impacts such as pollution. For example, it includes provisions for early warning across borders, joint monitoring and assessment, mutual assistance etc. The following activities and tools under the Water Convention support recovery and prevention:

• The Water Convention supports countries to develop or strengthen transboundary water agreements and joint institutions as key instruments to negotiate transboundary water management, including water quantity, water quality and health aspects. Transboundary cooperation, including in particular river basin organizations can play an important role in coordinating and supporting actions by riparian countries for COVID-19 recovery and prevention of future crisis; some of them already have health and mutual assistance in their mandate and already support countries in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic.

• The Water Convention helps transboundary basins to adapt to climate change through capacity building activities organized at the global level and support provided to specific basins in development and implementation of transboundary adaptation strategies and plans. These activities also promote better resilience of countries, basins and people to prevent future emergencies, as they address the projected variety in water resources quantity and quality and increase linkages between transboundary water cooperation, climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction.

• Performant monitoring and effective information exchange help to address emerging health concerns linked to water quality. The activities on data and information exchange and several guidance documents on monitoring and assessment developed under the Water Convention help to improve harmonized monitoring of waters (measuring, sampling, etc.) to ensure adequate and consistent information to inform decision-making in transboundary basins.

• Financing access to water and sanitation and transboundary water cooperation are increasingly important to prevent future crisis. The Water Convention guides the countries on funding and financing to support transboundary water cooperation processes.

• In countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia, the EU Water Initiative National Policy Dialogues on Integrated Water Resources Management and on Water Supply and Sanitation, implemented under the programmes of work of the Water Convention and the Protocol on Water and Health, provide platforms for regular dialogue on water management, water and sanitation issues, hygiene and water-related diseases. In 2020–2021, the National Policy Dialogue steering committees, bringing together national water, health, environment, finance and other ministries, discuss measures needed in the water sector and beyond for COVID-19 recovery, as well as prevention of and preparedness to similar outbreaks in the future.

• The Task Force on the Water-Food-Energy-Ecosystems Nexus under the Water Convention provides a global platform to share experience on intersectoral cooperation in transboundary contexts, which is of particular relevance in the phase of recovery, when more than ever, Governments will be prioritizing securing supply and affordability of these resources to all citizens, including those who are vulnerable.

The Protocol on Water and Health: Supporting prevention, preparadeness and recovery

The provision of safe and sufficient water and adequate sanitation and hygiene is key to protecting human health during the infectious disease outbreaks, such as also COVID-19. Frequent handwashing according to appropriate hygiene standards require a continuous supply of safe water, and sanitation systems that are operational, including under challenging conditions, such as due to a changing climate.

In order to achieve the Protocol’s objective of protecting human health and well-being through improving water management and preventing, controlling and reducing water-related disease (Article 1), countries should pursue the aim of ensuring access to drinking-water and provision of sanitation for everyone (Article 6). The fundamental requirements stemming from the above provisions are important pillars in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and in guiding recovery efforts, while promoting the progressive realization of human rights.

Through its governance and accountability framework, the Protocol can play a vital role in “building forward better and fairer” from the pandemic by promoting safe, resilient and equitable WASH services for all in all places, including in communities, health care facilities and schools, and organizing the exchange of good practices and mutual support across pan-European countries.

The Protocol requires Parties to set national targets on water, sanitation and health, regularly review them and report upon their implementation (Articles 6 and 7). As targets shall be periodically revised, countries can use such opportunity to review and amend them to respond to the priorities and needs arisen from the COVID-19 pandemic.

In accordance with Article 8, countries should establish, improve and maintain comprehensive national and/or local surveillance and early-warning systems, and prepare national and local contingency plans for responses to outbreaks of water-related disease, water quality incidents and risks. Although there is no evidence of waterborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2, surveillance of viral RNA in wastewater emerges as an important tool for timely and effective public health decision-making during the pandemic and can therefore be considered in further improving routine surveillance and early warning systems as defined in Article 8.

The more detailed requirements set by the Protocol and possible actions to support public health preparedness, response to and recovery from COVID-19 can be found here. These provide a conceptual framework that may support planning, financing, implementing and monitoring WASH interventions to prevent and control COVID-19 outbreaks, as well as other infectious diseases. Countries and partners may choose from the proposed action list and integrate them into national, local and setting-specific response and recovery plans.

Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability

The global outbreak of COVID-19 is affecting every part of human lives, including the physical world. A recent study on environemnatl effects of COVID indicates that the pandemic situation significantly improves air quality in different cities across the world, reduces GHGs emission, lessens water pollution and noise, and reduces the pressure on the tourist destinations, which may assist with the restoration of the ecological system. In addition, there are also some negative consequences of COVID-19, such as increase of medical waste, haphazard use and disposal of disinfectants, mask, and gloves; and burden of untreated wastes continuously endangering the environment. It seems that economic activities will return soon after the pandemic, and the situation might change. Hence, this study also outlines possible ways to achieve long-term environmental benefits. It is expected that the proper implementation of the proposed strategies might be helpful for the global environmental sustainability. Below a summary of this study is presented.

Environmental effects of COVID-19

The global disruption caused by the COVID-19 has brought about several effects on the environment and climate. Both positive and negative environmental impacts of COVID-19 are present in the Figure.

Positive environmental effects

Reduction of air pollution and GHGs emission. As industries, transportation and companies have closed down, it has brought a sudden drop of greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions. Compared with this time of last year, levels of air pollution in Ney York has reduced by nearly 50% because of measures taken to control the virus (Henriques, 2020). It was estimated that nearly 50% reduction of N2O and CO2 occurred due to the shutdown of heavy industries in China (Caine, 2020). Also, emission of NO2 is one of the key indicators of global economic activities, which indicates a sign of reduction in many countries (e.g., US, Canada, China, India, Italy, Brazil etc.) due to the recent shutdown (Biswal et al., 2020; Ghosh, 2020; Saadat et al., 2020; Somani et al., 2020). [...]

It is assumed that vehicles and aviation are key contributors of emissions and contribute almost 72% and 11% of the transport sector's GHGs emission respectively (Henriques, 2020). The measures taken globally for the containment of the virus are also having a dramatic impact on the aviation sector. Many countries restricted international travelers from entry and departure. Due to the decreased passengers and restrictions, worldwide flights are being cancelled by commercial aircraft companies. For instance, China reduces almost 50–90% capacity of departing and 70% domestic flights due to the pandemic, compared to January 20, 2020, which ultimately deducted nearly 17% of national CO2 emissions (Zogopoulos, 2020). Furthermore, it is reported that 96% of air travel dropped from a similar time last year globally due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Wallace, 2020), which has ultimate effects on the environment.

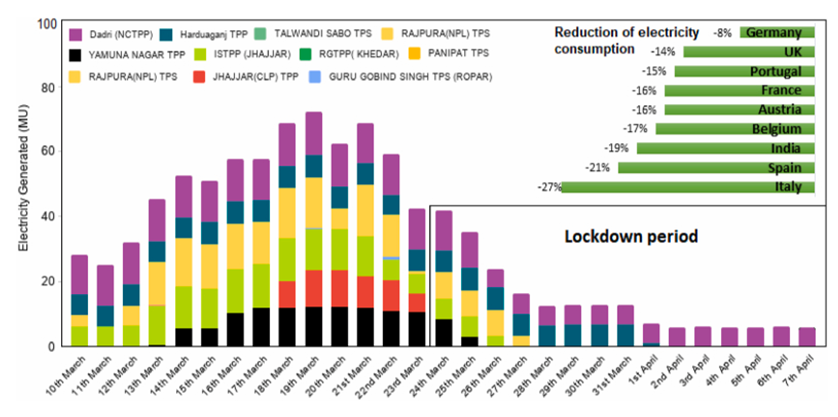

Overall, much less consumption of fossil fuels lessens the GHGs emission, which helps to combat against global climate change. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), oil demand has dropped 435,000 barrels globally in the first three months of 2020, compared to the same period of last year (IEA, 2020). Besides, global coal consumption is also reduced because of less energy demand during the lockdown period (Figure below). […]

Source: Armstrong, 2020; CREA, 2020

Reduction of water pollution. Water pollution is a common phenomenon of a developing country like India, and Bangladesh, where domestic and industrial wastes are dumped into rivers without treatment (Islam and Azam, 2015; Islam and Huda, 2016; Bodrud-Doza et al., 2020; Yunus et al., 2020). During the lockdown period, the major industrial sources of pollution have shrunk or completely stopped, which helped to reduce the pollution load (Yunus et al., 2020). For instance, the river Ganga and Yamuna have reached a significant level of purity due to the absence of industrial pollution on the days of lockdown in India. It is found that, among the 36 real-time monitoring stations of river Ganga, water from 27 stations met the permissible limit (Singhal and Matto, 2020). This improvement of water quality at Haridwar and Rishikesh was ascribed to the sudden drop of the number of visitors and 500% reduction of sewage and industrial effluents (Singhal and Matto, 2020; Somani et al., 2020). [...] It is reported that, due to the lockdown of COVID-19, the Grand Canal of Italy turned clear, and many aquatic species reappeared (Clifford, 2020). Water pollution is also reduced in the beach areas of Bangladesh, Malaysia, Thailand, Maldives, and Indonesia (Kundu, 2020; Rahman, 2020). Jribi et al. (2020) reported that, due to the COVID-19 lockdown, the amount of food waste is reduced in Tunisia, which ultimately reduces soil and water pollution. However, the amount of industrial water consumption is also reduced, especially from the textile sector around the globe (Cooper, 2020). Usually, huge amount of solid trashes is generated from construction and manufacturing process responsible for water and soil pollution, and it also reduced. Moreover, owing to the reduction of export-import business, the movement of merchant ship and other vessels is reduced globally, which also decreased emission as well as marine pollution.

Reduction of noise pollution. Noise pollution is the elevated levels of sound, generated from different human activities (e.g., machines, vehicles, construction work), which may lead to adverse effects on human and other living organisms (Goines and Hagler, 2007; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). Usually, noise negatively affects physiological health, along with cardiovascular disorders, hypertension, and sleep shortness of human (Kerns et al., 2018). It is reported that globally around 360 million people are prone to hearing loss due to noise pollution (Sims, 2020). World Health Organization predicted that in Europe alone, over 100 million people are exposed to high noise levels, above the recommended limit (WHO, 2012). Moreover, anthropogenic noise pollution has adverse impacts on wildlife through the changing balance in predator and prey detection and avoidance. Unwanted noise also negatively affects the invertebrates that help to control environmental processes which are vital for the balance of the ecosystem (Solan et al., 2016). However, the quarantine and lockdown measures mandate that people stay at home and reduce economic activities and communication worldwide, which ultimately reduced noise level in most cities (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). For instance, noise level of Delhi, the capital of India, is reduced drastically around 40–50% in the recent lockdown period (Somani et al., 2020). […] Moreover, due to travel restrictions, the number of flights and vehicular movements have drastically decreased around the world, which have ultimately reduced the level of noise pollution. For example, in Germany passenger air travel has been slashed by over 90%, car traffic has dropped by >50% and trains are running <25% than the usual rates (Sims, 2020). Overall, COVID-19 lockdown, and lessened economic activities reduced the noise pollution around the globe.

Ecological restoration and assimilation of tourist spots. Over the past few years, the tourism sector has witnessed a remarkable growth because of technological advancements and transport networks; which contribute significantly to global gross domestic product (GDP) (Lenzen et al., 2018). It is estimated that the tourism industry is responsible for 8% of global GHGs emission (Lenzen et al., 2018). However, the places of natural beauty (e.g., beaches, islands, national parks, mountains, desert and mangroves) usually attract the tourists, and make a huge harsh. To facilitate and accommodate them, lots of hotels, motel, restaurant, bar and market are built, which consume lots of energy and other natural resources (Pereira et al., 2017). For instance, Puig et al. (2017) calculated the carbon footprint of coastland hotel services of Spain and reported electricity and fuels consumption take a key role, and 2-star hotels have the highest carbon emissions. Moreover, visitors dump various wastes which impair natural beauty and create ecological imbalance (Islam and Bhuiyan, 2018). Due to the outbreak of COVID-19 and local restrictions, the number of tourists has dropped in the tourist spots around the world (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). For instance, Phuket, Thailand's most popular tourist's destination, with 5,452 visitors per day on average, goes into lockdown on April 9, 2020, due to the surge of Covid-19 (Cripps, 2020). Similarly, local administration imposed a ban on public gathering and tourist arrivals at Cox's Bazar sea beach, known as the longest unbroken natural sand sea beach in the world. As a result of restriction, the color of sea water is changed, which usually remain turbid because of swimming, bathing, playing and riding motorized boats (Rahman, 2020). Nature gets a time to assimilate human annoyance, and due to pollution reduction recently returning of dolphins was reported in the coast of Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh) and canals, waterways, and ports of Venice (Italy) after a long decade (Rahman, 2020; Kundu, 2020).

Negative environmental effects

Increase of biomedical waste generation. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, medical waste generation is increased globally, which is a major threat to public health and environment. For sample collection of the suspected COVID-19 patients, diagnosis, treatment of huge number of patients, and disinfection purpose lots of infectious and biomedical wastes are generated from hospitals (Somani et al., 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). For instance, Wuhan in China produced more than 240 metric tons of medical wastes every day during the time of the outbreak (Saadat et al., 2020), which is almost 190 m tonnes higher than the normal time (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). Again, in the city of Ahmedabad of India, the amount of medical waste generation increased from 550-600 kg/day to around 1000 kg/day at the time of the first phase of lockdown (Somani et al., 2020). Around 206 m tonnes of medical waste are generated per day in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh because of COVID-19 (Rahman et al., 2020). Also other cities like Manila, Kuala Lumpur, Hanoi, and Bangkok experienced similar increases, producing 154–280 m tonnes more medical waste per day than before the pandemic (ADB, 2020). Such a sudden rise of hazardous wastes and their proper management have become a significant challenge to the local waste management authorities. According to the recent published literature, it is reported that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can exist a day on cardboard, and up to 3 days on plastics and stainless steel (Van-Doremalen et al., 2020). So, waste generated from the hospitals (e.g., needles, syringes, bandage, mask, gloves, used tissue, and discarded medicines etc.) should be managed properly, to reduce further infection and environmental pollution, which is now a matter of concern globally.

Safety equipment use and haphazard disposal. To protect from the viral infection, presently peoples are using face mask, hand gloves and other safety equipment, which increase the amount of healthcare waste. It is reported that, in USA, trash amount has been increasing due to increased PPE use at the domestic level (Calma, 2020). Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the production and use of plastic based PPE is increased worldwide (Singh et al., 2020). For instance, China increased the daily production of medical masks to 14.8 million since February 2020, which is much higher than before (Fadare and Okoffo, 2020). However, due to lack of knowledge about infectious waste management, most people dump these (e.g., face mask, hand gloves etc.) in open places and in some cases with household wastes (Rahman et al., 2020). Such haphazard dumping of these trashes creates clogging in waterways and worsens environmental pollution (Singh et al., 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). It is reported that face mask and other plastic based protective equipment are the potential source of microplastic fibers in the environment (Fadare and Okoffo, 2020). Usually, Polypropylene is used to make N-95 masks, and Tyvek for protective suits, gloves, and medical face shields, which can persist for a long time and release dioxin and toxic elements into the environment (Singh et al., 2020). Though, experts and responsible authorities suggest for the proper disposal and segregation of household organic waste and plastic based protective equipment (hazardous medical waste), but mixing up these wastes increases the risk of disease transmission, and exposure to the virus of waste workers (Ma et al., 2020; Somani et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020).

Municipal solid waste generation, and reduction of recycling. Increase of municipal (both organic and inorganic) waste generation has direct and indirect effects on environment like air, water and soil pollution (Islam et al., 2016). Due to the pandemic, quarantine policies established in many countries have led to an increase in the demand of online shopping for home delivery, which ultimately increase the amount of household wastes from shipped package materials (Somani et al., 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). However, waste recycling is an effective way to prevent pollution, save energy, and conserve natural resources (Ma et al., 2019). But, due to the pandemic many countries postponed the waste recycling activities to reduce the transmission of viral infection. For instance, USA restricted recycling programs in many cities (nearly 46%), as government worried about the risk of COVID-19 spreading in recycling facilities (Somani et al., 2020). United Kingdom, Italy, and other European countries also prohibited infected residents from sorting their waste (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). Overall, due to disruption of routine municipal waste management, waste recovery and recycling activities, the landfilling and environmental pollutants increased worldwide.

Other effects on the environment. Recently, huge amount of disinfectants has been applied onto roads, in commercial, and residential areas to exterminate SARS-CoV-2 virus. Such extensive use of disinfectants may kill non-targeted beneficial species, which may create ecological imbalance (Islam and Bhuiyan, 2016). Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 virus was detected in the COVID-19 patient's faeces and also from municipal wastewater in many countries including Australia, India, Sweden, Netherlands and USA (Ahmed et al., 2020; Nghiem et al., 2020; Mallapaty, 2020). So, additional measures in wastewater treatment are essential, which is challenging for developing countries like Bangladesh, where municipal wastewater is drained into nearby aquatic bodies and rivers without treatment (Islam and Azam, 2015; Rahman and Islam, 2016). China has already strengthened the disinfection process (increased use of chlorine) to prevent SARS-CoV-2 virus spreading through the wastewater. But, the excessive use of chlorine in water could generate harmful by-product (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020).

Potential strategies of environmental sustainability

It is assumed that all of these environmental consequences are short-term. So, it is high time to make a proper strategy for long-term benefit, as well as sustainable environmental management. The COVID-19 pandemic has elicited a global response and made us united to win against the virus. Similarly, to protect the globe, the home of human beings, united efforts of the countries are imperative (Somani et al., 2020). Therefore, some strategies are proposed for global environmental sustainability.

1. Sustainable industrialization: Industrialization is crucial for economic growth; however, it's time to think about sustainability. For sustainable industrialization, it is essential to shift to less energy-intensive industries, use of cleaner fuels and technologies, and strong energy efficient policies (Pan, 2016). Moreover, industries should be built in some specific zones, keeping in mind that wastes from one industry can be used as raw materials of the other (Hysa et al., 2020). After a certain period of time, industrial zones should have been shut down in a circular way to reduce emission without hampering the national economy. Again, in industries, especially readymade garments (RMG) and others, where a huge number of people work, proper distance and hygienic environment should be maintained to reduce the spread of any infectious communicable disease.

2. Use of green and public transport: To reduce emissions, it is necessary to encourage people to use public transport, rather than private vehicles. Besides, people should be encouraged to use bicycle in a short distance, and public bike sharing (PBS) system (like China) should be available for mass usage, which is not only environmentally friendly but also beneficial for health.

3. Use of renewable energy: Use of renewable energy can lower the demand for fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas, which can play an important role in reducing the GHGs emissions (Ellabban et al., 2014; CCAC, 2019). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, global energy demand drops down, which results in the reduction of emission and increased ambient air quality in many areas (Somani et al., 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). But, to maintain the daily needs and global economic growth, it is not possible to cut-off energy demand like a pandemic situation. Hence, the use of renewable energy sources like solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal heat and biomass can meet the energy demand and reduce the GHGs emission (Ellabban et al., 2014).

4. Wastewater treatment and reuse: To face the challenges of water pollution, both industrial and municipal wastewater should be properly treated before discharge. Besides, reuse of treated wastewater in non-production processes like toilet flushing and road cleaning can reduce the burden of excess water withdrawal.

5. Waste recycling and reuse: To reduce the burden of wastes and environmental pollution, both industrial and municipal wastes should be recycled and reused. Hence, circular economy or circularity systems should be implemented in the production processes to minimize the use of raw material and waste generation (Hysa et al., 2020). Moreover, hazardous and infectious medical wastes should be properly managed by following the guidelines (WHO, 2020c). It is now clear that majority of people (especially in developing countries) lack the knowledge about waste segregation and disposal (Rahman et al., 2020). So, governments should implement extensive awareness campaigns through different mass media, regarding proper waste segregation, handling and disposal.

6. Ecological restoration and ecotourism: For ecological restoration, tourist spots should be periodically shut down. Moreover, ecotourism practices should be strengthened to promote sustainable livelihoods, cultural preservation, and biodiversity conservation (Islam and Bhuiyan, 2018).

7. Behavioral change in daily life: To reduce the carbon footprint and global carbon emission, it is necessary to change our daily behavior and optimize consumption; avoid processed and take locally grown food, make compost from food waste, switch off or unplug electronic devices when not used, and use a bicycle instead of a car for short(er) distances.

8. International cooperation: To meet the sustainable environmental goals and protect global environmental resources, such as global climate and biological diversity, combined international effort is essential (ICIMOD, 2020). Hence, the responsible international authority like the United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment) should take effective role to prepare time-oriented policies, arrange international conventions, and ensure coordination of global leaders for appropriate implementation.

Directly or indirectly, the pandemic affects human life and the global economy, which ultimately has effects on the environment and climate. It reminds us on how we have neglected the environmental elements and enforced human induced climate change. Moreover, the global response to COVID-19 also teaches us to work together to combat threats the mankind faces. Though the impacts of COVID-19 on the environment are short-term, united and time-oriented efforts can strengthen environmental sustainability and save the Earth from the effects of global climate change.

COVID-19: lessons for sustainability?

This briefing from the ‘Narratives for Change’ series reflects on the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and asks how these lessons can be applied to our quest for sustainability and how we can govern our societies in a way that respects planetary health as a precondition for human and economic health. Key messages include:

• COVID-19 can be seen as a ‘late lesson’ from an early warning. Environmental degradation increases the risk of pandemics. COVID-19 emerged and escalated through the complex interplay between drivers of change, such as ecosystem disturbance, urbanisation, international travel and climate change.

• The pandemic has shown that our societies have immense potential for collective action and change when faced with a perceived emergency.

• Thus far, the unprecedented agency shown by governments in responding to COVID-19 does not seem to have greatly served the cause of sustainability.

• Human health and environmental integrity are intertwined. A transition to a sustainable society and economy is necessary to protect human health.

• To ‘build back better’, society and governments must reflect on what to do differently and what to stop doing altogether.

Human Rights, the Environment and COVID-19

The COVID-19 crisis reveals a clear truth about catastrophic risk in an increasingly globalized world: an effective response requires immediate, ambitious and evidence-based preventive action at the international level. To avert future global threats, including pandemics, we must protect rights to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment upon which we all depend for our health and wellbeing. A human rights-based approach to the COVID-19 crisis is also needed to address its unequal impacts on the poor, vulnerable and marginalized and its underlying drivers, including environmental degradation. The following key messages summarized by UNEP, COVID-19 Response and UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner on human rights, the environment and COVID-19 highlight essential human rights obligations and responsibilities of States and others, including businesses, in addressing and responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

1. Fulfil the Right to a Healthy Environment

Environmental degradation and biodiversity loss create the conditions for an increase in the type of animal-to-human zoonosis that can result in viral epidemics. They also contribute to pre-existing medical conditions, such as asthma, that make persons more vulnerable to viral infections. More than 150 countries recognize the right to a safe, clean and healthy environment in some form. The substantive elements of this right include a safe climate, water and sanitation, clean air, healthy and sustainably produced food, non-toxic environments, healthy ecosystems and biodiversity. These elements are prerequisites for human health and resilience in the face of illness and for reducing the risk of zoonosis and expansion of existing disease vectors. According to the Human Rights Committee, environmental degradation is one of “the most pressing and serious threats to the ability of present and future generations to enjoy the right to life” and protecting the human right to life “depends on measures taken by States parties to protect the environment”. The COVID-19 response should respect, protect and fulfil rights to a healthy environment.

2. Re-Think Our Interactions with Nature

The COVID-19 pandemic should push us all to rethink our interactions with nature and wildlife. Around 60 percent of all infectious diseases and 75 percent of all emerging infectious diseases in humans, including COVID-19, are zoonotic. On average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every four months. Ecosystem integrity is the foundation of human health and development. Human-induced environmental changes modify wildlife population structure and reduce biodiversity, resulting in new conditions that favour particular hosts, vectors, and/or pathogens. Integrating the human right to a healthy environment in key environmental agreements and processes, such as the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, is critical to a holistic response to COVID-19 that includes reconceptualization of the relationship between people and nature that will reduce risks and prevent future harms from environmental degradation.

3. Protect Those Living in Poverty or Subject to Discrimination

The poor and marginalized are among those worst impacted by both COVID-19 and environmental harms such as climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution that threaten full and effective enjoyment of all human rights. Environmental harms disproportionately impact individuals, groups and peoples already living in vulnerable situations – including women, children, the poor, minorities, migrants, indigenous peoples, and persons with disabilities. Crises such as COVID-19 amplify those impacts, including through adverse effects on access to food and land, water and sanitation, housing, livelihoods, decent work, healthcare and other basic necessities. Fulfilling human rights, including the human right to a healthy environment, not only reduces disproportionate impacts, it also fosters more resilient societies. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that society can only be as healthy as its most vulnerable members. The COVID-19 response should address inequalities and focus on protection of persons in vulnerable situations in order to leave no one behind.

4. Strengthen Environmental Rule of Law and Protect Environmental Human Rights Defenders

The COVID-19 crisis requires us to reconsider the policies and practices that have contributed to our current situation. Rather than rolling back environmental laws and policies, it is time to step up environmental protection and enforcement in order to create resilience and reduce future pandemic risks, bearing in mind that short-term economic gains from deregulation often come at long-term costs.

States should recognize the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment in their constitutional and legislative frameworks, with effective remedies for violations of this right. At practical level, States can, for example, strengthen efforts to combat illegal trade in wildlife – reducing potential avenues for zoonosis and promoting the rule of law while ensuring alternative and sustainable livelihoods.

Tourism fees often fund parks and conservation efforts. The COVID-19 crisis jeopardizes this revenue stream and funding against poaching, illegal wildlife trade and other forms of prohibited exploitation of natural resources, placing increased pressure on natural systems. Effective and inclusive conservation efforts are essential to protect healthy ecosystems and the communities that depend on them. Environmental human rights defenders are essential allies in efforts to protect the environment and, by extension, human health during the COVID-19 crisis. Action is needed to protect both the environment and its defenders including, in many cases, Indigenous Peoples, whose worldviews and traditional knowledge can bring critical perspectives for sustainable and rights-based development. Limitations on civic space undermine the crucial advocacy of environmental human rights defenders, which in turn can pave the way for short-sighted and dangerous actions. Defenders should be empowered and protected from threats, reprisals, and harassment, including as relating to emergency decrees and legislation.

5. Guarantee Meaningful and Informed Participation

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and other international human rights instruments establish that participation and access to information are human rights. The importance of participation and access to information in environmental matters has been frequently reaffirmed, including by Rio Principle 10, the Paris Agreement, the Aarhus Convention and the Escazu Agreement.

Governments and businesses should be transparent in sharing relevant information related to their efforts to address environmental and health crises and ensuring the informed participation of all persons in decision-making processes that affect them. During this crisis, Governments and the international community should find new ways and modalities of working.

Environmental governance should be modernized, including through inclusive and rights-based tools for digital participation and access to information, ensuring that essential environmental decision-making continues in an inclusive and effective manner regardless of the exigencies posed by COVID-19.Meaningful, informed and effective participation of all people is not just their human right, it also leads to more effective, equitable and inclusive environmental action.

Drawing on the diverse interests, needs and expertise of all people, including women and girls, local communities and indigenous peoples, offers important insights for inclusive and sustainable environmental action. The COVID-19 crisis should be a catalyst for further democratization of environmental decision-making at all levels through improved use of digital space and inclusive consultative processes.

6. Minimize the Harmful Impacts of Medical Waste

The COVID-19 response has led to increased use of medical supplies, including testing kits and protective equipment, as well as packaging/delivery supplies such as single use plastics. Effective and comprehensive waste management, including medical, household and other hazardous waste, is critical to minimize possible secondary impacts on health and the environment caused by the COVID-19 response.

The poorest, most vulnerable and marginalized communities without access to waste management or sanitation infrastructure have been, and will continue to be, hit the hardest by secondary effects on health, livelihood and rights. Preventing environmental harm and ensuring the full and effective implementation of basic human rights such as those to health, a healthy environment, and water and sanitation, is critical to prevent and minimize the risk of infectious diseases.

States and other duty-bearers should ensure the safe handling and disposal of waste as a vital component of an effective and comprehensive emergency response and treat waste management, including of medical, household and other hazardous waste, as an urgent and essential public service. Effective and equitable management of biomedical and health-care waste should be guaranteed through appropriate identification, collection, separation, storage, transportation, treatment, protection, training and disposal.

7. Build Back Better

A rights-based approach to the COVID-19 recovery and response requires that we build back better and more sustainably. Economic stimulus packages should protect and benefit the most vulnerable while advancing efforts to fulfil human rights, achieve the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, and limit global heating to the greatest extent possible.

The response to the crisis presents an opportunity to support improved social protection measures, and a just transition to a sustainable, no-carbon economy founded on renewable energy, environmentally sound technology, sustainable resource use, community empowerment and livelihoods of dignity.

States should work jointly and individually to mobilize the maximum available resources toward building back better. Country-level socioeconomic impact analysis of COVID-19, the Common Country Analysis, UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks and the UN Secretary-General’s Call to Action for Human Rights are important entry points for building back better and for operationalizing the human right to a healthy environment.

The rights of all people to benefit from science and its applications must also be safeguarded ensuring that solutions to global problems, like a vaccine for COVID-19 or environmentally sound technologies, are equitably shared by all. Over the long run, inclusive, sustainable and equitable economies are more robust.

All States have an obligation to pursue development that benefits both people and the planet and equitably distribute the benefits thereof. Businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights and it is also in their best interest to pursue sustainable development

8. Learn from the COVID-19 Crisis

In the face of global risks, rapid, evidence-based, participatory and collective action not only produces the best results, it is also fulfilling human rights obligations. Effective responses to COVID-19 and environmental crises should be global responses grounded in solidarity, compassion, respect for human dignity and ecological integrity.

The required actions and international cooperation must build on obligations of States and other duty-bearers in international legal frameworks and instruments such as the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the Declaration on the Right to Development, and the Rio Declaration.

Collaboration between governments, international partners, civil society, activists, the private sector, and all individuals and peoples are needed to fulfil human rights, including rights to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, and to achieve sustainable development that equitably meets the needs of present and future generations.