Section 12. Thematic reviews

12.1. Climate Change

State of Climate in 2021

According to the provisional WMO Report “State of the Global Climate 2021”, past 7 years set to be the warmest on record. A temporary cooling “La Nina” event early in the year means that 2021 is expected to be “only” the fifth to seventh warmest year on record. But this does not negate or reverse the long-term trend of rising temperatures. Global sea level rise accelerated since 2013 to a new high in 2021, with continued ocean warming and ocean acidification.

Key messages

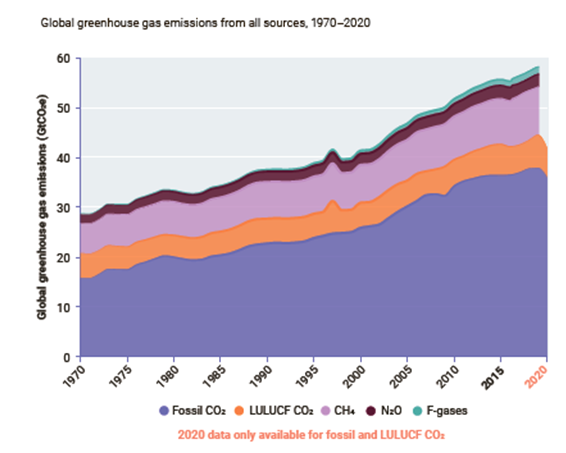

Greenhouse gases. In 2020, greenhouse gas concentrations reached new highs. Levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) were 413.2 parts per million (ppm), methane (CH4) at 1889 parts per billion (ppb) and nitrous oxide (N2O) at 333.2 ppb, respectively, 149%, 262% and 123% of pre-industrial (1750) levels. The increase has continued in 2021.

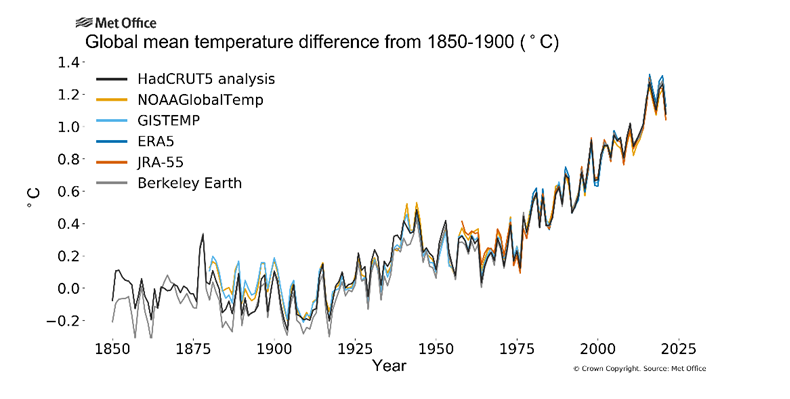

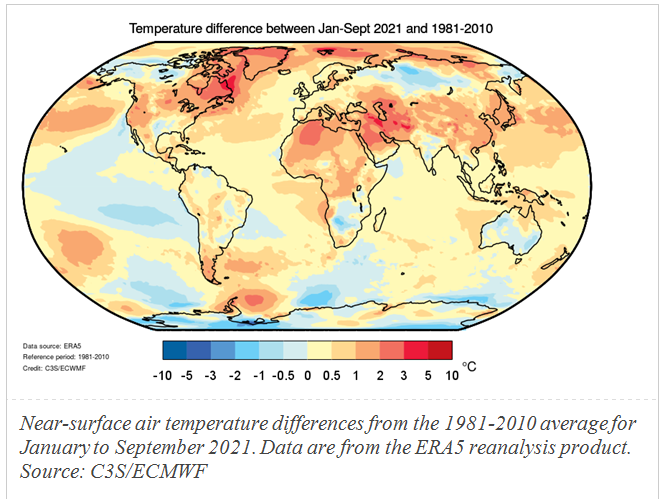

Temperatures. The global mean temperature for 2021 (based on data from January to September) was about 1.09°C above the 1850-1900 average. Currently, the six datasets used by WMO in the analysis place 2021 as the sixth or seventh warmest year on record globally. But the ranking may change at the end of the year. It is nevertheless likely that 2021 will be between the 5th and 7th warmest year on record and that 2015 to 2021 will be the seven warmest years on record.

2021 is less warm than recent years due to the influence of a moderate La Nina at the start of the year. La Nina has a temporary cooling effect on the global mean temperature and influences regional weather and climate. The imprint of La Nina was clearly seen in the tropical Pacific in 2021. 2021 is around 0.18°C to 0.26 °C warmer than 2011.

Ocean. Much of the ocean experienced at least one ‘strong’ Marine Heatwave at some point in 2021 – with the exception of the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean (due to La Nina) and much of the Southern Ocean. The Laptev and Beaufort Sea in the Arctic experienced “severe” and “extreme” marine heatwaves from January to April 2021.

The ocean absorbs around 23% of the annual emissions of anthropogenic CO2 to the atmosphere and so is becoming more acidic. Open ocean surface pH has declined globally over the last 40 years and is now the lowest it has been for at least 26,000 years. Current rates of pH change are unprecedented since at least that time. As the pH of the ocean decreases, its capacity to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere also declines.

Sea level. Global mean sea level changes primarily result from ocean warming via thermal expansion of sea water and land ice melt. Measured since the early 1990s by high precision altimeter satellites, the mean global mean sea level rise was 2.1 mm per year between 1993 and 2002 and 4.4 mm per year between 2013 and 2021, an increase by a factor of 2 between the periods.

Sea ice. Arctic sea ice was below the 1981-2010 average at its maximum in March. Sea-ice extent then decreased rapidly in June and early July in the Laptev Sea and East Greenland Sea regions. As a result, the Arctic-wide sea-ice extent was record low in the first half of July. There was then a slowdown in melt in August, and the minimum September extent (after the summer season) was greater than in recent years at 4.72 million km2. It was the 12th lowest minimum ice extent in the 43-year satellite record, well below the 1981-2010 average. Sea-ice extent in the East Greenland Sea was a record low by a large margin.

Antarctic sea ice extent was generally close to the 1981–2010 average, with an early maximum extent reached in late August.

Glaciers and ice sheets. Mass loss from North American glaciers accelerated over the last two decades, nearly doubling for the period 2015-2019 compared to 2000-2004. An exceptionally warm, dry summer in 2021 in western North America took a brutal toll on the region's mountain glaciers.

The Greenland Ice Sheet melt extent was close to the long-term average through the early summer. But temperatures and meltwater runoff were well above normal in August 2021 as a result of a major incursion of warm, humid air in mid-August.

Extreme weather. Exceptional heatwaves affected western North America during June and July, with many places breaking station records by 4°C to 6°C and causing hundreds of heat-related deaths.

There were also multiple heatwaves in the southwestern United States. Death Valley, California reached 54.4 °C on 9 July, equalling a similar 2020 value as the highest recorded in the world since at least the 1930s. It was the hottest summer on record averaged over the continental United States. There were numerous major wildfires. The Dixie fire in northern California, had burned about 390,000 hectares, the largest single fire on record in California.

Extreme heat affected the broader Mediterranean region. On 11 August, an agrometeorological station in Sicily reached 48.8 °C, a provisional European record, while Kairouan (Tunisia) reached a record 50.3 °C. Montoro (47.4 °C) set a national record for Spain on 14 August, while on the same day Madrid had its hottest day on record with 42.7 °C. On 20 July, Cizre (49.1 °C) set a Turkish national record and Tbilisi (Georgia) had its hottest day on record (40.6 °C). Major wildfires occurred across many parts of the region with Algeria, southern Turkey and Greece especially badly affected.

Abnormally cold conditions affected many parts of the central United States and northern Mexico in mid-February. The most severe impacts were in Texas, which generally experienced its lowest temperatures since at least 1989. An abnormal spring cold outbreak affected many parts of Europe in early April.

Precipitation. The city of Zhengzhou on 20 July received 201.9 mm of rainfall in one hour (a Chinese national record). Flash floods were linked to more than 302 deaths, with reported economic losses of US$17.7 billion.

Western Europe experienced some of its most severe flooding on record in mid-July. Western Germany and eastern Belgium received 100 to 150 mm over a wide area on 14-15 July over already saturated ground, causing flooding and landslides and more than 200 deaths. The highest daily rainfall was 162.4 mm at Wipperfurth-Gardenau (Germany).

Persistent above-average rainfall in the first half of the year in parts of northern South America, particularly the northern Amazon basin, led to significant and long-lived flooding in the region. The Rio Negro at Manaus (Brazil) reached its highest level on record. Floods also hit parts of East Africa, with South Sudan being particularly badly affected.

Significant drought affected much of subtropical South America for the second successive year. Rainfall was well below average over much of southern Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and northern Argentina. The drought led to significant agricultural losses, exacerbated by a cold outbreak at the end of July, damaging many of Brazil’s coffee-growing regions. Low river levels also reduced hydroelectricity production and disrupted river transport.

Socio-economic and environmental impacts. In the last ten years, conflict, extreme weather events and economic shocks have increased in frequency and intensity. The compounded effects of these perils, further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to a rise in hunger and, consequently, undermined decades of progress towards improving food security.

Following a peak in undernourishment in 2020 (768 million people), projections indicated a decline in global hunger to around 710 million in 2021 (9%). However, as of October 2021, the numbers in many countries were already higher than in 2020.

Extreme weather during the 2020/2021 La Nina altered rainfall seasons contributing to disruptions to livelihoods and agricultural campaigns across the world. Extreme weather events during the 2021 rainfall season have compounded existing shocks. Consecutive droughts across large parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America have coincided with severe storms, cyclones and hurricanes, significantly affecting livelihoods and the ability to recover from recurrent weather shocks.

Extreme weather events and conditions, often exacerbated by climate change, have had major and diverse impacts on population displacement and on the vulnerability of people already displaced throughout the year. From Afghanistan to Central America, droughts, flooding and other extreme weather events are hitting those least equipped to recover and adapt.

Ecosystems – including terrestrial, freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems – and the services they provide, are affected by the changing climate. In addition, ecosystems are degrading at an unprecedented rate, which is anticipated to accelerate in the coming decades. The degradation of ecosystems is limiting their ability to support human well-being and harming their adaptive capacity to build resilience.

Source: WMO

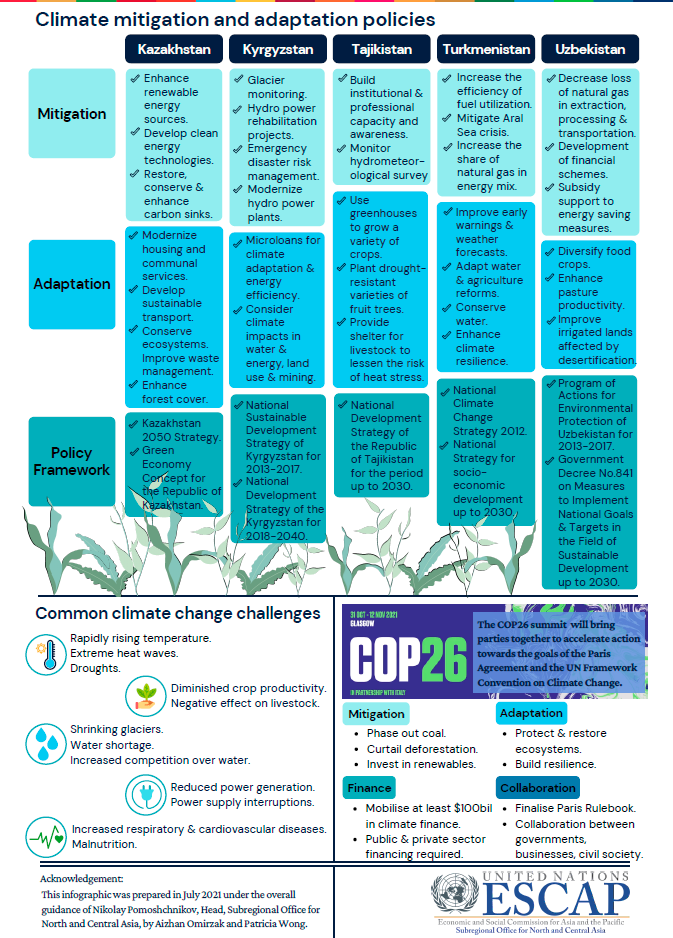

Climate Change Agreement

All five Central Asian countries ratified the Paris Agreement and submitted their first nationally determined contributions (NDCs). The infographic below summarizes the mitigation and adaptation plans in Central Asia countries, as well as the policy frameworks that guide these plans and strategies. To meet the emission reduction targets set out, Central Asia countries need to improve energy efficiency and integrate green economy strategies, especially in agriculture and industrial processes.

Joint Statement of the C5+1 on addressing the climate crisis. Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and the USA made collective and country commitments on addressing the climate crisis. They underlined that climate change already negatively impacts the availability of water in the region, accelerates desertification and land degradation.

The C5+1 countries pledged their NDCs would include specific targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and concrete actions to reach those targets; acknowledged the critical need for the world to work together to advance the transition to a net-zero, clean-energy future by mid-century; noted the significant potential for regional collaboration toward advancing that objective, in areas such as the development of the use of renewable energy and methane abatement; expressed concern about the large-scale consequences of the drying up of the Aral Sea; confirmed their interest in mitigating consequences of climate change in Central Asia through high-tech innovations, environmentally friendly, energy, and water-saving technologies, preventing further desertification and potential climate migration, as well as the development of ecotourism. The C5+1 governments will plan for the Energy and Environment Working Group to meet ahead of COP26 in Glasgow and discuss actions to combat climate change.

Commitments made by the C5+1 countries. Uzbekistan intends to submit an enhanced and ambitious NDC aligned with 1.5 degrees Celsius by COP26. Uzbekistan will include its renewable energy target of 25 percent by 2030, enshrined in Uzbekistan national law. Kazakhstan has committed to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and reach 15 percent share of renewables by 2030. Kyrgyzstan is in the final stages of considering a revised NDC of 16 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions below business-as-usual levels and 44 percent reduction conditional on international support. The NDC of the United States is to achieve an economy-wide target of reducing its net greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52 percent below 2005 levels in 2030. The United States also aims to decarbonize its electricity system by 2035.

COP 26

For two weeks, the world was riveted on all facets of climate change — the science, the solutions, the political will to act, and clear indications of action. The COP26 brought together 120 world leaders and over 40,000 registered participants.

The outcome of COP26 – the Glasgow Climate Pact – is the fruit of intense negotiations among almost 200 countries over the two weeks, strenuous formal and informal work over many months, and constant engagement both in-person and virtually for nearly two years.

Cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions are still far from where they need to be to preserve a livable climate, and support for the most vulnerable countries affected by the impacts of climate change is still falling far short. But COP26 did produce new “building blocks” to advance implementation of the Paris Agreement through actions that can get the world on a more sustainable, low-carbon pathway forward.

What was agreed?

Recognizing the emergency. Countries reaffirmed the Paris Agreement goal of limiting the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C. And they went further, expressing “alarm and utmost concern that human activities have caused around 1.1 °C of warming to date, that impacts are already being felt in every region, and that carbon budgets consistent with achieving the Paris Agreement temperature goal are now small and being rapidly depleted.” They recognized that the impacts of climate change will be much lower at a temperature increase of 1.5 °C compared with 2 °C.

Accelerating action. Countries stressed the urgency of action “in this critical decade,” when carbon dioxide emissions must be reduced by 45 per cent to reach net zero around mid-century. But with present climate plans – the Nationally determined Contributions — falling far short on ambition, the Glasgow Climate Pact calls on all countries to present stronger national action plans next year, instead of in 2025, which was the original timeline. Countries also called on UNFCCC to do an annual NDC Synthesis Report to gauge the present level of ambition.

Moving away from fossil fuels. In perhaps the most contested decision in Glasgow, countries ultimately agreed to a provision calling for a phase-down of coal power and a phase-out of “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies – two key issues that had never been explicitly mentioned in decisions of UN climate talks before, despite coal, oil and gas being the main drivers of global warming. Many countries, and NGOs, expressed dissatisfaction that the language on coal was significantly weakened (from phase-out to phase-down) and consequently, was not as ambitious as it needs to be.

Delivering on climate finance. Developed countries came to Glasgow falling short on their promise to deliver US$100 billion a year for developing countries. Voicing “regret,” the Glasgow outcome reaffirms the pledge and urges developed countries to fully deliver on the US$100 billion goal urgently. Developed countries, in a report, expressed confidence that the target would be met in 2023.

Stepping up support for adaptation. The Glasgow Pact calls for a doubling of finance to support developing countries in adapting to the impacts of climate change and building resilience. This won’t provide all the funding that poorer countries need, but it would significantly increase finance for protecting lives and livelihoods, which so far made up only about 25 per cent of all climate finance (with 75 per cent going towards green technologies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions). Glasgow also established a work programme to define a global goal on adaptation, which will identify collective needs and solutions to the climate crisis already affecting many countries.

Completing the Paris rulebook. Countries reached agreement on the remaining issues of the so-called Paris rulebook, the operational details for the practical implementation of the Paris Agreement. Among them are the norms related to carbon markets, which will allow countries struggling to meet their emissions targets to purchase emissions reductions from other nations that have already exceeded their targets. Negotiations were also concluded on an Enhanced Transparency Framework, providing for common timeframes and agreed formats for countries to regularly report on progress, designed to build trust and confidence that all countries are contributing their share to the global effort.

Focusing on loss & damage. Acknowledging that climate change is having increasing impacts on people especially in the developing world, countries agreed to strengthen a network— known as the Santiago Network – that connects vulnerable countries with providers of technical assistance, knowledge and resources to address climate risks. They also launched a new “Glasgow dialogue” to discuss arrangements for the funding of activities to avert, minimize and address loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change.

New deals and announcements

There were many other significant deals and announcements – outside of the Glasgow Climate Pact – which can have major positive impacts if they are indeed implemented. These include:

Forests. 137 countries took a landmark step forward by committing to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. The pledge is backed by $12bn in public and $7.2bn in private funding. In addition, CEOs from more than 30 financial institutions with over $8.7 trillion of global assets committed to eliminate investment in activities linked to deforestation.

Methane. 103 countries, including 15 major emitters, signed up to the Global Methane Pledge, which aims to limit methane emissions by 30 per cent by 2030, compared to 2020 levels. Methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, is responsible for a third of current warming from human activities.

Cars. Over 30 countries, six major vehicle manufacturers and other actors, like cities, set out their determination for all new car and van sales to be zero-emission vehicles by 2040 globally and 2035 in leading markets, accelerating the decarbonization of road transport, which currently accounts for about 10 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Coal. Leaders from South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Germany, and the European Union announced a ground-breaking partnership to support South Africa – the world’s most carbon-intensive electricity producer— with $8.5 billion over the next 3-5 years to make a just transition away from coal, to a low-carbon economy.

Private finance. Private financial institutions and central banks announced moves to realign trillions of dollars towards achieving global net zero emissions. Among them is the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, with over 450 firms across 45 countries that control $130 trillion in assets, requiring its member to set robust, science-based near-term targets.

Central Asian countries in СОР26

Draft Regional Statement of CA countries. For the first time in the 26-year history of the UNFCCC, the CA countries presented themselves as a single region and voiced a draft Regional statement appealing to the international community, primarily the UN structures, to pay special attention to the critical problems of the CA region caused by climate change and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan. The document emphasizes the special geographical position of Central Asia, which has no access to the oceans and seas, which significantly increases its vulnerability to climate change. Particular attention is also paid to the importance of joining forces to combat climate change and adapt to its impacts at the regional and international levels.

Appeal by NGOs of the Central Asian countries on climate change. The main message of the Regional Appeal announced at COP26 is an appeal to the governments of Central Asia to strengthen national and regional programs to prevent the climate crisis in the region. The governments of the countries should "adopt stronger goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and take a more proactive position in promoting the region's interests and role in international climate commitments and processes.”

In addition, NGOs from CA countries are calling on the authorities to create non-declarative legislative conditions to support renewable energy sources, abandon the construction of nuclear power plants and fossil fuels subsidies. The civil sector sees the climate sustainability of the region in strengthening measures to restore and preserve the fertility of soil, mountain, forest, pasture and aquatic ecosystems. It considers it necessary to disseminate climate-resilient technologies at the state level. The appeal also notes the importance of taking into account the transboundary nature of water resources, environmental and climatic risks and opportunities.

Climate Change Reports

The 10 New Insights in Climate Science 2021 report is based on an assessment made by more than 60 world-leading academic experts.

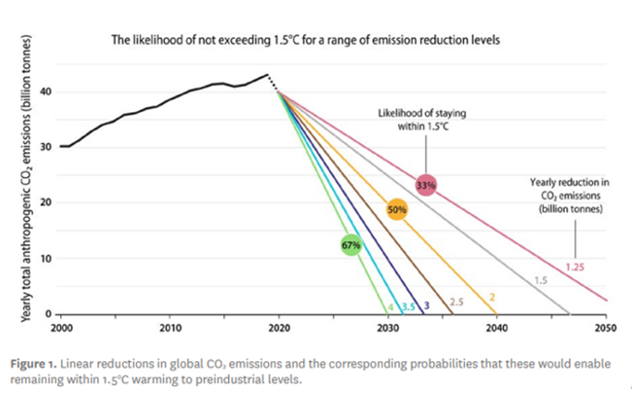

1. Stabilizing at 1.5°C warming is still possible, but immediate and drastic global action is required: (1) Estimates of the remaining global carbon budget (the overall amount of CO2 that can be emitted) indicate that rapid reductions averaging 2 gigatonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) (5% of 2020 global emissions) per year are required to keep global warming to within 1.5°C. This pace of reductions must be maintained until net emissions are zero (around 2040); (2) We may have already exceeded the carbon budget necessary to keep global temperature rise to within 1.5°C of warming; (3) If these unprecedented cuts in emissions are not made, we are likely to exceed 1.5oC warming and require carbon removal technologies on an enormous scale; (4) The short-term emissions drop during the COVID-19 pandemic had a very limited impact on the overall decarbonization towards meeting the 1.5°C target; (5) The power sector offers the largest opportunity for near-term decarbonization, but all economic sectors need to drastically reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

2. Rapid growth in methane and nitrous oxide emissions put us on track for 2.7°C warming: (1) Reducing methane emissions is a key lever available to slow climate change over the next 25 years: readily available, low-cost measures (see implications below) could halve methane emissions by 2030 and must go hand-in-hand with CO2 mitigation and removal efforts to stabilize global temperature in the long term; (2) Rapid reductions in aerosol emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic caused a slight warming of the planet, highlighting the fact that cooling aerosols emitted from fossil fuel combustion to date have partly masked warming from greenhouse gas emissions. While declines in aerosol emissions will improve air quality and benefit the health of billions, this will exacerbate global warming in the short term.

3. Megafires – Climate change forces fire extremes to reach new dimensions with extreme impacts: (1) We are entering a new age of intensifying extreme fire regimes (megafires). It is likely that these are induced, and certainly exacerbated, by anthropogenic climate change; (2) Several megafires have been observed across very diverse regions from high to low latitudes, and are now impacting ecosystems; (3) Megafires can affect entire biomes with unprecedented impacts on flora and fauna, threatening also more fire-sensitive ecosystems such as the World Heritage–listed Gondwana rainforests of Australia; (4) Large smoke plumes and aerosols from megafires can impact wide areas due to long-range transport both in the troposphere and stratosphere; (5) More frequent and more intense fires come with increased risks to respiratory and cardiovascular health, birth outcomes and mental health for rural and urban communities.

4. Climate tipping elements incur high-impact risks: (1) The IPCC AR6 acknowledges that many human-caused changes, especially to the ocean, ice sheets and global sea level, are high risk and irreversible for centuries to millennia – some of them involving tipping processes – and that these changes are key to a comprehensive risk assessment; (2) Significant destabilization of several key climate tipping elements is already being observed today; (3) In many cases, the dominant driver of this destabilization is global warming. But direct human influence on land cover change, such as degradation and active deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, can play an equal or even stronger role; (4) Some tipping elements, for example melting ice sheets and changes to ocean currents, but also deforestation of rainforests, influence each other. Recent research indicates that interactions among tipping elements can ultimately cause shifts to happen at lower levels of global warming than anticipated.

5. Global climate action must be just: (1) Climate action must support just transitions, as it could otherwise slow down improvements in living standards in low- and middle-income countries and burden disadvantaged people globally; (2) Working towards just, equitable and low-carbon development for poorer countries: requires the richest 1% to cut their emissions by a factor of 30, which would enable the poorest 50% of the world’s population to increase their emissions up to three-fold; (3) Justice-oriented climate action is more likely to achieve public acceptance, improving uptake of implementation.

6. Supporting household behaviour changes is a crucial but often overlooked opportunity for climate action: (1) Fighting climate change means making changes in lifestyles, particularly for the wealthy, to complement efficiency and decarbonization strategies; (2) Sticking to the status quo in terms of consumption growth puts any supply-side decarbonization achievements at risk (e.g. solar deployment); (3) For changes in individual behaviour to make a difference, they must be combined with mutually reinforcing changes by the public and business sectors; (4) Lifestyles compatible with the 1.5°C goal can result in a “good life” for all (i.e., “1.5°C lifestyles”).

7. Political challenges impede effectiveness of carbon pricing: (1) Carbon pricing has not yet delivered substantial emissions reductions; (2) To be effective, carbon prices need to increase rapidly in the near term, be sector-specific and be part of larger policy packages; (3) To be publicly accepted, carbon pricing schemes need to consider equity and justice.

8. Nature-based solutions are critical for the pathway to Paris – but look at the fine print: (1) Nature-based Solutions (NbS) can offer multiple benefits to climate, ecosystems and societies, but must not replace or delay decarbonization efforts in other sectors; (2) With further warming, Earth System feedbacks may increasingly destabilize ecosystems and undermine the long-term mitigation potential of NbS; (3) Investing in NbS now to protect biodiversity will make them more climate resilient and strengthen their ability to act as long-term carbon sinks; (4) Much potential for NbS is situated in the less developed and developing countries and in areas inhabited by indigenous peoples who often have limited land rights; (5) To successfully include NbS in National Determined Contributions (NDCs) and effectively implement policies and direct funding, comprehensive metrics and monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) are needed that include biodiversity, ecosystem services and local livelihoods, alongside carbon sequestration.

9. Building resilience of marine ecosystems is achievable by climate-adapted conservation and management, and global stewardship: (1) The oceans play a key role in regulating the Earth’s climate. Protecting the oceans as a carbon sink including marine sediments and vegetation that bind substantial carbon stocks (“blue carbon”) is an important climate change mitigation action; (2) Integrated, tailored and innovative solutions are needed to preserve ocean ecosystems threatened by accelerating climate change and other anthropogenic pressures; (3) There is a growing recognition of the importance of integrated governance in building ocean resilience by: involving all levels from local to global as well as the private sector; providing clear targets, strong actions and global stewardship; (4) In expanding the global network of MPAs the adaptation measures must include climate refugia, areas of high environmental change, corridors for migrating species.

10. Costs of climate change mitigation can be justified by the multiple immediate benefits to the health of humans and nature: (1) Benefits of mitigation to human health and nature accrue before the benefits of mitigation are apparent; (2) Health benefits are of higher economic value than the cost of mitigation policies; (3) Rapid emission reductions are needed across all sectors; adopting the right policies can make a big difference to health and wider environmental benefits; (4) The value of health co-benefits can justify rapid scaling up of mitigation policies and technologies, and thus accelerate progress towards a zero-emissions economy.

Source: 10insightsclimate.science

IPCC report shows that climate change is rapid, widespread and intensifying

The IPCC finalized the first part of the Sixth Assessment Report, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, the Working Group I contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. It provides the clearest and most comprehensive assessment to date of warming of the atmosphere, oceans and land. The scale of recent changes is unprecedented in thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years. Many changes due to past and future greenhouse gas emissions are irreversible for centuries to millennia, especially changes in the ocean, ice sheets and global sea level, says the report.

Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. Evidence of observed changes in extremes such as heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts, and the proportion of intense tropical cyclones, and, in particular, their attribution to human influence, has strengthened since the last IPCC Assessment Report in 2014.

More Extreme Weather. The IPCC report projects that in the coming decades climate changes will increase in all regions. For 1.5°C of global warming, there will be increasing heat waves, longer warm seasons and shorter cold seasons as well as changes in precipitation patterns affecting flooding and drought occurrences. At 2°C of global warming, heat extremes would more often reach critical tolerance thresholds for agriculture and health, the report shows.

The extreme heat we have witnessed in 2021 bears all the hallmarks of human-induced climate change. British Columbia in Canada recorded an incredible temperature of 49.6°C – breaking all previous records - as part of an intense and extensive heatwave in North America.

The Arctic is heating more than twice as fast as the global average. Further warming will amplify permafrost thawing, and the loss of seasonal snow cover, melting of glaciers and ice sheets, and loss of summer Arctic sea ice, according to the report. The report shows also how climate change is intensifying the water cycle. This brings more intense rainfall and associated flooding, as well as more intense drought in many regions.

1.5°C warming level. The observed average rate of heating accelerated during the period 2006-2018 compared to the period 1971-2006. The report provides new estimates of the chances of crossing the global warming level of 1.5°C in the next decades, and finds that unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C will be beyond reach.

Emissions of greenhouse gases from human activities are responsible for approximately 1.1°C during the last ten years of warming since 1850-1900. In 2020 the annual mean temperature was 1.2 C above the normal. The averaged temperature estimate over the next 20 years is expected to reach or exceed 1.5°C of warming. The Paris Agreement commits to pursue efforts to limit temperature increase to this level.

Regional emphasis. many drivers of climate impacts are projected to change in all regions of the world. Region-specific changes include intensification of tropical cyclones and extratropical storms, increases in river flooding, reductions in mean precipitation, increases in aridity and increases in fire weather.

Even at 1.5 °C of warming, heavy precipitation and associated flooding are projected to intensify and become more frequent in most regions in Africa and Asia with a high level of confidence. More frequent and severe droughts are projected in a few regions in all continents except Asia. These changes increase at 2 °C of warming. The report is available here.

The Emissions Gap Report 2021: The Heat Is On is the 12th edition in UNEP annual series that provides an overview of the difference between where greenhouse emissions are predicted to be in 2030 and where they should be to avert the worst impacts of climate change.

1. Following an unprecedented drop of 5.4 per cent in 2020, global carbon dioxide emissions are bouncing back to pre-COVID levels, and concentrations of GHGs in the atmosphere continue to rise.

2. New mitigation pledges for 2030 show some progress, but their aggregate effect on global emissions is insufficient. As at 30 September 2021, 120 countries (121 parties, including the European Union and its 27 member states) representing just over half of global GHG emissions, have communicated new or updated NDCs. This year's assessment considers the new or updated NDCs communicated to the UNFCCC as well as announcements of new mitigation pledges for 2030 by China, Japan and the Republic of Korea not submitted as NDCs by 30 September.

3. As a group, G20 members are not on track to achieve either their original or new 2030 pledges. Ten G20 members are on track to achieve their previous NDCs, while seven are off track.

4. A promising development is the announcement of long-term net-zero emissions pledges by 52 parties, covering more than half of global emissions. However, these pledges show large ambiguities.

5. Few of the G20 members' NDC targets put emissions on a clear path towards net-zero pledges. There is an urgent need to back these pledges up with near-term targets and actions that give confidence that net-zero emissions can ultimately be achieved and the remaining carbon budget kept.

6. The emissions gap remains large: compared to previous unconditional NDCs, the new pledges for 2030 reduce projected 2030 emissions by only 7.5 per cent, whereas 30 per cent is needed for 2°C and 55 per cent is needed for 1.5°C.

7. Global warming at the end of the century is estimated at 2.7°C if all unconditional 2030 pledges are fully implemented and 2.6°C if all conditional pledges are also implemented. If the net-zero emissions pledges are additionally fully implemented, this estimate is lowered to around 2.2°C.

8. The opportunity to use COVID-19 fiscal rescue and recovery spending to stimulate the economy while fostering a low-carbon transformation has been missed in most countries so far. Poor and vulnerable countries are being left behind.

9. Reduction of methane emissions from the fossil fuel, waste and agriculture sectors can contribute significantly to closing the emissions gap and reduce warming in the short term.

10. Carbon markets can deliver real emissions abatement and drive ambition, but only when rules are clearly defined, designed to ensure that transactions reflect actual reductions in emissions, and supported by arrangements to track progress and provide transparency.

The 5th Yearbook of Global Climate Action 2021. This Yearbook of Global Climate Action reviews the work carried out under the Marrakech Partnership and the High-Level Champions since the last publication, by: (1) summarizing the state and scope of global climate action in 2021 and the challenges and opportunities around how to track and reflect these efforts, as well as the progress of the global action tools launched in the past year; (2) outlining the key messages around what is needed to accelerate sectoral systems transformation; and (3) presenting the Champions’ vision on the future of the climate action framework and agenda, and how the work feeds into the global stocktake.

Significant and Major Events

Water and Climate Coalition. A new Water and Climate Coalition has been launched to achieve more effective integrated policy-making in an era when climate change, environmental degradation and population growth has exacerbated water-related hazards and scarcity. The coalition aims to achieve an integrated global Water and Climate Agenda to support more effective adaptation and resilience and speeding up progress towards SDGs 6 and 13 (climate). The coalition includes current and former government, business and civil society leaders as well as 2 youth representatives from all regions of the world. The Water and Climate Leaders will provide practical guidance on proper integration, information, cooperation and investment.

The UN Security Council held several high level open debates: (1) “Addressing climate-related security risks to international peace and security through mitigation and resilience building” (February 23); (2) “Security in the context of climate change” (September 23); (3) “Security in the context of terrorism and climate change” (Deember 9) (see Security Council).

United States organized the Leaders Summit on Climate, which brought together 40 heads of state – from big Russia, Brazil and China to tiny Bhutan, Gabon and Marshall Islands. “We are at the verge of the abyss… Global temperature has already risen 1.2 degrees Celsius – racing toward the threshold of catastrophe”, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in his address to the virtual climate summit (April 22).

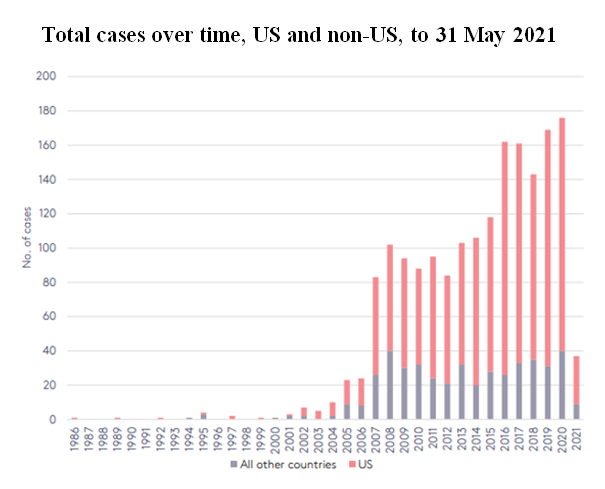

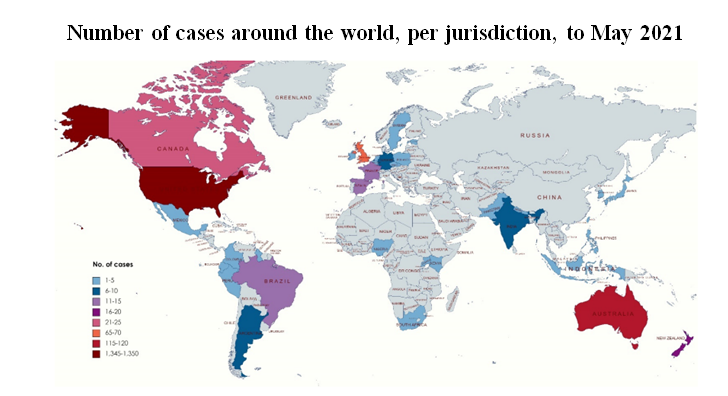

Global trends in climate change litigation in 2021. The databases contained 1,841 ongoing or concluded cases of climate change litigation from around the world, as of May 2021 (see Figure below). Of these, 1,387 were filed before courts in the United States, while the remaining 454 were filed before courts in 39 other countries and 13 international or regional courts and tribunals (including the courts of the European Union). Outside the US, Australia (115), the UK (73) and the EU (58) remain the jurisdictions with the highest volume of cases. 1,006 cases have been filed since 2015 – the year of the Paris Agreement and the landmark case of Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands – while 834 were filed between 1986 and 2014.

New cases, 1 May 2020 to 31 May 2021. Globally, 191 new cases were filed in this period. Cases were filed for the first time in Guyana and Taiwan, as well as the East African and European Courts of Human Rights.

Source: Setzer J. and Higham С. (2021) Global trends in climate change litigation: 2021 snapshot. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

Climate change litigation is gaining momentum. The world's first courtroom battle with corporate titans took place in 2021. The Dutch environmental group Milieudefensie succeeded in the court in the Netherlands which ordered global energy company Royal Dutch Shell PLC (RDS) to reduce its group-wide CO2 emissions by 45 percent by the end of 2030 alleging Shell’s contributions to climate change violate human rights. In January, the environmental group demanded that 30 major corporate emitters of greenhouse gases with legal bases in the Netherlands, including BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, KLM and Unilever present concrete and feasible climate plans outlining how they would trim emissions of the heat-trapping gases by 45% from 2019 levels by 2030 during next three months.

On November 25, three young climate activists – Marina Tricks (19), Adetola Onamade (23) and Jerry Kobina Amokwandoh (22) - opend the campaign “Young People vs UK Gov” appealing to the Great Britain’s Supreme Court to consider the case to influence the country climate policy. The defendants try to file a case against the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak and the Energy Minister, Kwasi Kwarteng, over the Government’s failure to honour its Paris Agreement commitments.

Juliana v. United States climate change lawsuit. The first case of its kind, Juliana v. the United States continued in 2021. 21 American teenagers aged from 9 to 20 filed a lawsuit against the US Government. Their complaint asserts that, through the government's affirmative actions that cause climate change, it has violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, as well as failed to protect essential public trust resource. State of things: the youth plaintiffs are awaiting a ruling on their Motion for Leave to File a Second Amended Complaint and the Motion to Intervene filed by 18 states, led by Alabama.