Section 12. Thematic reviews

12.5. Sardoba Dam Collapse

General Information

The Sardoba is a reservoir built to supply irrigation water to six districts in Syrdarya and Djizzak provinces of Uzbekistan. The total capacity is 974 mcm, including the useful capacity of 922 mcm. The reservoir’s perimeter is 42 km; the dam’s length is 28 km, and, the area is 6,800 ha. The reservoir is 28.8 meters deep. The maximum dam height is 33 meters, with the maximum water level of 30 meters.

Construction of the reservoir in the territory of Sardoba, Mirzaabad and Khavast districts began in 2010 following the Governmental Decree and was completed in 2017. By January 2017, the total cost of construction reached 1.3 trillion soums ($404.4 million). The customer of the facility was the State unitary enterprise “Sirdaryosuvkurilishinvest” of the then Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources. The Project designed by OOO “UzGip” was implemented by State unitary enterprise “Uztemiryulkurilishmontazh" of the Uzbekistan railways company.

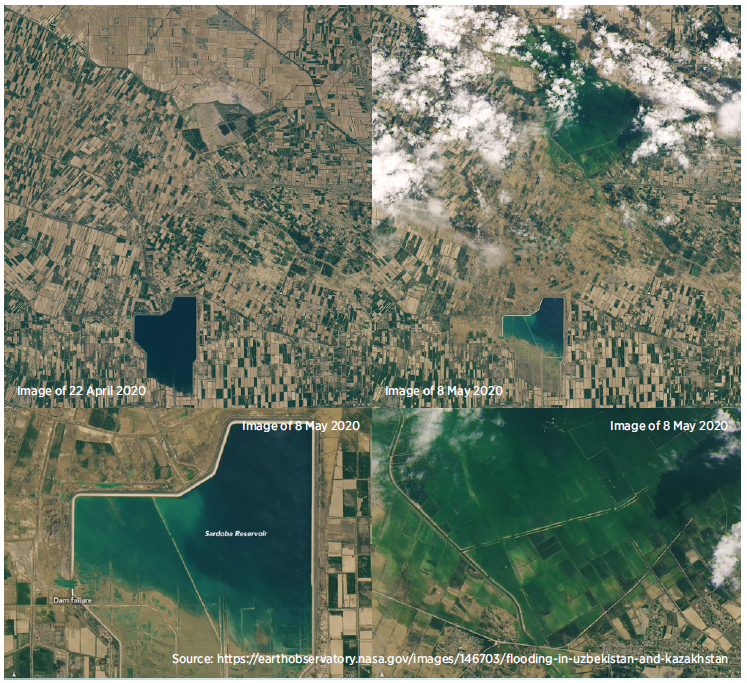

Based on satellite imagery, accumulation of water started in winter 2013/2014 and by 30 April the reservoir was almost filled, with the water volume exceeding the maximum design values. Constriction of a small 10.7 MW hydropower plant at the reservoir was started in April 2020. The plant designed for generation of 41.1 MkWh is to be completed by the end of 2022.

Dam burst and flooding

On the 1st of May, the dam burst. The poured water was turned to the Abay Canal in the Akaltyn district and then into the Arnasay lake system in Djizzak province. The gates were also opened so that water could flow into the irrigation canal network. As a result of inflow of 180 m3/s, the Central Golodnostepskiy Collector, given its flow capacity of 120 m3/s, was overfilled with water, with the resulting flooding. The water surface area of the reservoir halved, while the water volume decreased by more than 70%.

Effects and emergency relief in Uzbekistan

The flood critically damaged settlements and crops in the Sardoba, Akaltyn and Mirzaabad districts. Buildings, roads, and communications were flooded. More than 90 thousand people had to be evacuated from 23 villages in the three districts; 56 people were hospitalized; 4 people died.

Shavkat Mirziyoyev at the Sardoba reservoir

Source: Press-service of the President of Uzbekistan

As reported by the Ministry of Emergency Situations of Uzbekistan, 32 381 hectares were damaged by flooding in the above districts. 23 settlements, 4711 domestic buildings and 277 non-residential buildings, as well as 30 718 ha of cropland were affected. Preliminary figure of damage from flooding was more than $4.3 million.

A special governmental commission was formed for emergency relief. A territory over 2 Mm2 were disinfected in 12 485 dwelling buildings, 748 shops, 304 administrative buildings, 31 markets and 540 roads. In order to improve the environmental situation, 6 086 t of wastes and 13 620 t of floodwater were removed from the affected area. Flood damaged roads and electric and gas networks were repaired.

Leading international experts from France, Turkey and Russia were invited to make an external expertise of this technogenic catastrophe.

The law enforcement agencies have opened a criminal case on the Sardoba dam against 17 persons, including the client (GUP “Syrdaryo Kurilishinvest”), the designer (OOO “Uzgip”), the main contractor (UP “Uztemiryolkurilishmontaj”), contractors (Rezaksoi Suv Kurilish, Omad Dubl, Sariosiyo kurilish, Trans Servis Complex, Topalang Sherobod), and officials of the Uzbek Ministry of Water Management and the Operations Administration.

As the Prosecutor General’s Office reported, the dam burst was caused by mistakes and defects in project design, construction and operation. Proceedings were initiated for a number of articles, including stealing, breach of water use, abuse of authority, neglect of official duty, forgery in public office, and violation of safety rules during construction. The Supreme Court of Uzbekistan started holding hearings in private on 21 December 2020 and passed a sentence upon 17 persons on 10 May 2021.

Effects and emergency relief in Kazakhstan

In the Kazakh territory, 5 settlements (Zhanaturmys, Zhenis, Firdousi, Dostyk, and Orgebas) that were home to 6,211 people have been flooded in the Makhtaaral district. 1030 residential buildings, 3 schools, 5 kindergartens, 4 health-care buildings, 10 trade points, roads, a bridge and 5 695 ha of agricultural land were flooded. The damage from flooding amounted to 31.7 billion tenge. There were no human losses.

The flooding area was mapped, and ambulance and rescue services were set in motion. In total, 1635 persons, 297 machines, 17 boats and 220 motor pipes were deployed in rescue operations. Additional forces were deployed from Almaty, Kyzylorda, Zhambyl provinces and Shymkent. 223 specialists, 62 units of equipment, 100 units of water pumping equipment were sent from Uzbekistan for help. 30,606 people and 15,171 heads of domestic animals were evacuated from flooded and endangered settlements. A total of 11,798,000 l of water have been pumped out to safe areas. 931 dead domestic animals (mainly from the territory of Uzbekistan) were extracted from water. An area of 2.8 Mm2 was decontaminated.

Since a state of emergency was declared, the Government of Kazakhstan allocated 552 million tenge to 5,524 residents of 5 settlements affected by the accident, with each resident getting 100,000 tenge. Additionally, the Fund of Alisher Usmanov transferred $1000 to each of 5,318 personal accounts of families living in 5 affected villages and 8 evacuated settlements (Myrzakent, Zhailybaev, Nurlytan, Shugyla, Zhantaksai, Nurlyzhol, Arayly, Akzhol).

Cooperation between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan

Immediately after the accident, it was reported that Kazakhstan was preparing a note for the Uzbek Foreign Ministry and would demand compensation for damage. But on 5 May, the Kazakh Foreign Ministry claimed that sending of the note to Uzbekistan was no longer in question, and the parties jointly planned recovery. Uzbekistan quickly provided more than 150 units of equipment and more than 200 specialists to help eliminate consequences of the accident in the territory of Kazakhstan. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan also provided their help. In the course of the year, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan closely coordinated the recovery operations: regular contacts were maintained between the heads of state and governments of the two countries. Environment Minister Mirzagaliev of Kazakhstan and Water Minister Khamraev of Uzbekistan met several times. The parties negotiated a draft Agreement on joint management and use of transboundary waters (see more details in Meetings of the Working Group on Water Management), signed a Roadmap on water cooperation between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and agreed to jointly conduct a technical audit of the Sardoba reservoir with national and international experts.

Prime-Ministers of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan lay the foundation of a new neighborhood in Myrzakent village,

Turkestan province in Kazakhstan, 10 May

Source

eeting of ministers: Sh. Khamraev (left) and M. Mirzagaliev (right), 2 July

Source

Cooperation between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in elimination of consequences of the Sardoba dam collapse was highly apprized from international experts. As the Global Observatory for Water and Peace notes:

“In spite of the COVID-19 crisis, and despite a history of water mismanagement and regional tensions in the Syr Darya river basin, both countries managed not only to cooperate over the immediate recovery, but also to strengthen good neighborly relations, taking further steps towards joint management of the shared basin. They thus effectively turned water from a potential source of conflict into an opportunity for cooperation and peace. A first important milestone was reached on July 2, 2020 with the signing of a joint roadmap for transboundary water management. The Sardoba dam disaster could become a watershed in reshaping the transboundary water dynamics in Central Asia, which are central to the COVID-19 response and recovery. Indeed, strengthened regional water cooperation could become a driver of sustainable socio-economic recovery in a profoundly changed world economy, fostering peace and security.”

Expert Opinion of Prof. V.A. Dukhovniy: Omissions and Lessons

The history of hydrotechnical construction in Uzbekistan is a continuous line of improvement of water development and management in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya basins. The hydrotechnical construction in Uzbekistan has been always advanced both in the Soviet Union and all over the world – starting from Farkhad HPP put into operation in 1948 and almost parallel commissioning of the Bozsu cascade of small HPPs on the Chirchik River followed by construction of such large structures as Kattagurgan, Tuyabuguz, and Takhiatash hydroschemes, Pachkamar reservoir. The Uzbek Ministry of Water Resources launched such unique large structures as the Tuyamuyun hydroscheme, with its 8 billion m3 reservoir on the Amu Darya River, the Andizhan reservoir with a unique buttress dam, and, eventually, the Talimarjan reservoir with more than 1 billion m3 hydraulic fill dam. All those structures have been operating successfully and reliably for a long time, without causing any concerns.

Thus, it is particularly bitter to see the accident that took place on the Sardoba reservoir on 1 May 2020 and caused huge economic damage to the whole Central branch of the South Golodnostepskiy Canal. The exemplary irrigation system built in the sixties virtually has been destroyed. The troubled waters have destroyed more than dozen kilometers of main and inter-farm canals and collecting drains that maintained irrigated land. Investigative authorities carried out the instructions of the President that all guilty persons should be held to accountable, and design and construction flaws were thoroughly investigated. It is also important to openly study engineering and water-management causes that led to the accident so that to learn lessons for the future.

Design and construction of the Sardoba reservoir represent a chain of ill-thought and insufficiently economically sound decisions.

1. Since the Toktogul hydroscheme had been converted to energy generation mode and water delivery in summer had decreased on average by 4.5 km3, it became necessary to buy energy from Kyrgyzstan to ensure water releases or, at least, to compensate a portion of this undersupply of water through additional storage in river’s middle reaches. By the 1998 Agreement concluded between the riparian countries of the Syr Darya river basin, water and energy were delivered to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in summer, while in winter the downstream countries supplied energy to Kyrgyzstan and a small portion to Tajikistan. In 2001, the Agreement stopped to be effective. Uzbekistan decided to build reservoirs to accumulate winter flow. Those plans included the Sardoba reservoir as well. From today’s perspective, this decision was rather wrong in terms of comparative costs for construction of compensating reservoirs. However, that time this line of conduct was chosen to overcome flow-regulation pressure from the side of upstream countries.

2. The cost of water in the Sardoba reservoir is estimated at 45 cents per 1 km3 (construction costs of $404.4 million per useful volume of 922 Mm3). By re-calculating for electricity supplied simultaneously with water by the Naryn hydropower cascade, the cost of electricity at the current value will be 0.12 x 0.45 = 0.057 dollars per kWh, which is 40% more expensive than the price of electricity supplied to external consumers by "Kyrgyzenergo" (4 cents/1 km3). Certainly, it would have been necessary to negotiate annually the conditions of energy sale and water supply, but this would have saved Uzbekistan from unnecessary capital investments and the emergency situation. Moreover, construction of the Sardoba reservoir per se caused significant damage to irrigated agriculture in the Syrdarya province, because 6,500 ha of irrigated land were withdrawn and another 8,000 ha was submerged in the Mekhnatabad district. But no one, of course, could have assumed the scale of destruction and the cost of recovery after the accident.

3. Fairly, location of the reservoir at the tail of the Central branch of South Golodnostepskiy Canal was quite unfavorable, first, due to geological conditions. The reservoir is located in the periphery of alluvial cone of watercourses flowing from the Turkestan ridge and the alluvial sediments bed at different depths under modern sediments of steppe landscape at the boundary of Sardoba depression. Due to such complex geomorphology, there are interbedded gypsum-bearing soils in the site of the reservoir. Moreover, such soils have different degrees of solubility: from dense lime horizons to slowly dissolving gypsum “chimneys” that during the period of less than one year dissolve and create a good basis for intrusion of water. The same phenomena were observed during construction of a reservoir in an experimental farm of the Central Asian Irrigation Research Institute (SANIIRI) – the state farm “1a” named by G.Gulyam. However, in addition to gypsum, subsiding loess soil that nosed in this zone from neighboring farms posed a risk in the bed of reservoir dams. Therefore, a very detailed survey of soils in the basement was needed before location of the reservoir with the head of 30 m. But even in case of detailed study conducted in advance, no one could exclude a possibility of seepage under dam embankment or subsidence of the dam itself in such complex soils. Hence, this required drainage of a dam, a piezometrical network, laboratory monitoring of soil density, consolidation tests of the soil in the basement, and thorough monitoring by skilled operations staff. Besides, the burst on the left side of the dam, which was not the highest point of the dam – could occur if this site was in the subsiding basement and the status of the dam was not monitored regularly. But most probably this was due to seepage in the basement or failure to observe the required soil density in the dam embankment.

4. It is unclear why so many companies were involved in construction and operation? Why the national railway company took part in the construction, given that hydrotechnical and railway construction requirements are different? Finally, why operation of the reservoir was not developed by the Ministry of Water Management and again was transferred to the railroad company?

As we can see, there were many risk factors, which had to be taken into account by designers, expertise, builders and operators in the selected site. Hence, this leads to a conclusion that the national water sector requires serious capacity building efforts.