Section 12. Thematic reviews

12.1. Climate Change

Extreme weather combined with COVID-19 in a double blow for millions of people in 2020. However, the pandemic-related economic slowdown failed to put a brake on climate change drivers and accelerating impacts, according to a new report compiled by WMO and an extensive network of partners.

State of the Climate Indicators in 2020

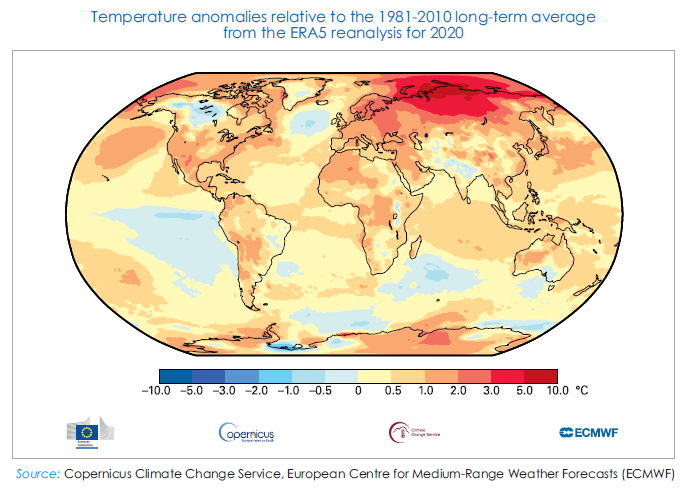

Temperature. 2020 was one of the three warmest years on record, despite a cooling La Nina event. The global average temperature was about 1.2°C above the pre-industrial (1850-1900) level. The six years since 2015 have been the warmest on record. 2011-2020 was the warmest decade on record.

Greenhouse gases. Concentrations of the major greenhouse gases continued to increase in 2019 and 2020. Globally averaged mole fractions of carbon dioxide (CO2) have already exceeded 410 parts per million (ppm), and if the CO2 concentration follows the same pattern as in previous years, it could reach or exceed 414 ppm in 2021, according to the report. The economic slowdown temporarily depressed new greenhouse gas emissions, according to UNEP, but had no discernible impact on atmospheric concentrations.

Oceans. The ocean absorbs around 23% of the annual emissions of anthropogenic CO2 into the atmosphere and acts as a buffer against climate change. The ocean also absorbs more than 90% of the excess heat from human activities. 2019 saw the highest ocean heat content on record, and this trend likely continued in 2020. Over 80% of the ocean area experienced at least one marine heatwave in 2020. The percentage of the ocean that experienced “strong” marine heat waves (45%) was greater than that which experienced “moderate” marine heat waves (28%).

Cryosphere. The 2020 Arctic sea-ice extent minimum after the summer melt was 3.74 million km2, marking only the second time on record that it shrank to less than 4 million km2. Record low sea-ice extents were observed in the months of July and October. Record high temperatures north of the Arctic Circle in Siberia triggered an acceleration of sea-ice melt in the East Siberian and Laptev Seas, which saw a prolonged marine heatwave. The Antarctic sea-ice extent remained close to the long-term average.

The Antarctic ice sheet has exhibited a strong mass loss trend since the late 1990s. This trend accelerated around 2005, and currently, Antarctica loses approximately 175 to 225 Gt per year, due to the increasing flow rates of major glaciers in West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula. A loss of 200 Gt of ice per year corresponds to about twice the annual discharge of the river Rhine in Europe.

Floods and droughts. Heavy rain and extensive flooding occurred over large parts of Africa and Asia in 2020. Heavy rain and flooding affected much of the Sahel and the Greater Horn of Africa, triggering a desert locust outbreak.

The Indian subcontinent and neighboring areas, China, the Republic of Korea and Japan, and parts of South-East Asia also received abnormally high rainfall at various times of the year.

Severe drought affected many parts of the interior of South America in 2020, with the worst-affected areas being northern Argentina, Paraguay and the western border areas of Brazil. The estimated agricultural losses were near US $3 billion in Brazil, with additional losses in Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. Long-term drought continued to persist in parts of southern Africa, particularly the Northern and Eastern Cape Provinces of South Africa.

Heat and fire. In a large region of the Siberian Arctic, temperatures in 2020 were more than 3°C above average, with a record temperature of 38°C in the town of Verkhoyansk. This was accompanied by prolonged and widespread wildfires.

In the USA, the largest fires ever recorded occurred in late summer and autumn. Widespread drought contributed to the fires, and July to September were the hottest and driest on record for the southwest. Death Valley in California reached 54.4°C on 16 August, the highest known temperature in the world in at least the last 80 years.

In the Caribbean, major heatwaves occurred in April and September. Cuba saw a new national temperature record of 39.7°C on 12 April. Further extreme heat in September saw national or territorial records set for Dominica, Grenada and Puerto Rico.

Australia broke heat records in early 2020, including the highest observed temperature in an Australian metropolitan area, in western Sydney, when Penrith reached 48.9°C.

The summer was very hot in parts of East Asia. Hamamatsu (41.1°C) equaled Japan’s national record on 17 August.

Europe experienced drought and heatwaves during summer 2020, although these were generally not as intense as in 2018 and 2019. In the eastern Mediterranean with all-time records set in Jerusalem (42.7°C) and Eilat (48.9°C) on 4 September, following a late July heatwave in the Middle East in which Kuwait Airport reached 52.1°C and Baghdad 51.8°C.

Tropical Cyclones. With 30 named storms, the 2020 North Atlantic hurricane season had its largest number of named storms on record. There were a record 12 landfalls in the United States of America, breaking the previous record of nine. Hurricane Laura reached category 4 intensity and made landfall on 27 August in western Louisiana, leading to extensive damage and US$ 19 billion in economic losses. Laura was also associated with extensive flood damage in Haiti and the Dominican Republic in its developing phase. The last storm of the season, Iota, was also the most intense, reaching category 5 before landfall in Central America. Cyclone Amphan, which made landfall on 20 May near the India-Bangladesh border, was the costliest tropical cyclone on record for the North Indian Ocean, with reported economic losses in India of approximately US$14 billion. The strongest tropical cyclone of the season was Typhoon Goni (Rolly). It crossed the northern Philippines with a 10-minute mean wind speed of 220 km/h (or higher) at its initial landfall, making it one of the most intense landfalls on record (1 November). Tropical Cyclone Harold had significant impacts in the northern islands of Vanuatu on 6 April, affecting about 65% of the population and also resulting in damage in Fiji, Tonga and the Solomon Islands. Storm Alex in early October brought extreme winds to western France, whilst heavy rain extended across a wide area. Other major severe storms included a hailstorm in Calgary (Canada) on 13 June, with insured losses exceeding US $1 billion and a hailstorm in Tripoli (Libya) on 27 October, with hailstones as large as 20 cm, accompanied by unusually cold conditions.

Lessons and opportunities for enhancing climate action

According to the International Monetary Fund, while the current global recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may make it challenging to enact the policies needed for mitigation, it also presents opportunities to set the economy on a greener path by boosting investment in green and resilient public infrastructure, thus supporting GDP and employment during the recovery phase.

Adaptation policies aimed at enhancing resilience to a changing climate, such as investing in disaster-proof infrastructure and early warning systems, risk sharing through financial markets, and the development of social safety nets, can limit the impact of weather-related shocks and help the economy recover faster.

Source: WMO

Climate Change Agreement

On 12 December 2015, a historic climate agreement was signed in Paris, uniting all countries of the world in the desire to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, switch to clean energy sources and adapt to the effects of climate change. How did these 5 years go for the post-Soviet countries? “The approved commitments and plans of no country in the EECCA region are considering reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2030,” says the new CAN EECCA report “Climate Policy Analysis of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia”. The report includes data for Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Russia and Ukraine.

In the countries of Central Asia, when planning climate policy, considerable attention is paid to climate change adaptation. Problems begin at the implementation level, because in general adaptation projects are either not linked by one systematic approach, or are very vague, without an action plan.

This year Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have officially announced the revision of their contributions to the Paris Agreement. Moldova made its second contribution to the UNFCCC in March, and Ukraine and Georgia will soon approve the updated NDCs. So far, these contributions either do not imply a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, or provide a very small percentage of reduction, which does not contribute to the implementation of the Paris Agreement goals.

The 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) to UNFCCC. The COP26 UN Climate Change Conference, hosted by the UK in partnership with Italy, will take place from 31 October to 12 November 2021 in the Scottish Event Campus (SEC) in Glasgow, UK. In light of the worldwide effects of COVID-19, the Conference was re-scheduled initially slated for November 2020. Rescheduling the conference ensures that all parties can focus on the issues to be discussed at this vital conference and allows more time for the necessary preparations to take place.

Reports on Climate Change

A new ICRC report , When Rain Turns to Dust, explores how countries enduring conflict are disproportionately affected by climate change and climate variability.

Here are seven things you need to know.

1. Of the 25 countries deemed most vulnerable to climate change, 14 are mired in conflict

The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Index looks at a country's vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges, set against its ability to improve resilience. Yemen, Mali, Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Somalia, all of which are dealing with conflict, are among the lowest ranked. This is not to say that there is a direct correlation between climate change and conflict. Rather, it suggests that countries enduring conflict are less able to cope with climate change, precisely because their ability to adapt is weakened by conflict. People living in conflict zones are therefore among the most vulnerable to the climate crisis and most neglected by climate action.

2. Climate change does not directly cause conflict, but...

Scientists generally agree that climate change does not directly cause armed conflict, but that it may indirectly increase the risk of conflict by exacerbating existing social, economic and environmental factors. For example, when cattle herders and agricultural farmers are pushed to share diminishing resources due to a changing climate, this can stir tensions in places that lack strong governance and inclusive institutions.

3. Insecurity limits people's ability to cope with climate shocks The following case study from Mali, which has seen years of conflict, illustrates this point. In early 2019, grazing land became scarce south of Gao, due to floods. Pastoralists were worried about travelling with their livestock for fear of being attacked by armed groups or bandits. Instead, they often gathered in areas close to water sources, creating tensions with farmers and fishermen. Insecurity prevented them from reaching livestock markets further afield, where they could have hoped for better prices. State officials – and potential state support – were absent because of the violence. Violence also considerably limited humanitarian access. In short, impoverished herders watched their only assets wither and were left struggling to feed their families.

4. Adapting to climate change can be relatively simple, but it tends to be complicated

In certain circumstances, a change in the crops being cultivated might be sufficient. But adapting to climate change may also require major social, cultural or economic changes. A whole agricultural system might need to change, or diseases new to a geographical area might need to be dealt with. Concerted efforts to adapt tend to be limited in times of war. In a conflict situation, authorities and institutions are not only weak, but also preoccupied with security priorities.

5. The natural environment is frequently a casualty of conflict

Too often, the natural environment is directly attacked or damaged by warfare. Attacks can lead to water, soil and land contamination, or release pollutants into the air. Explosive remnants of war can contaminate soil and water sources, and harm wildlife. Such environmental degradation reduces people's resilience and ability to adapt to climate change.

The indirect effects of conflict can also result in further environmental degradation, for example: authorities are less able to manage and protect the environment; large-scale displacement places strain on resources; natural resources can be exploited to sustain war economies. In Fao, south of Basra, Iraq, people blame their water and farming problems on the felling of date palms for military purposes during the Iran-Iraq war.

Conflict can also contribute to climate change. For example, the destruction of large areas of forest, or damage to infrastructure such as oil installations or big industrial facilities, can have detrimental climate consequences, including the release of large volumes of greenhouse gases into the air.

6. International humanitarian law (IHL) provides protection to the natural environment

As early as 1977, states afforded the natural environment protection against widespread, long-term and severe damage through Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions.

Greater respect for the rules of war can reduce the harm and risks that conflict-affected communities are exposed to as a result of climate change.

For example, climate change can drive water scarcity and reduce the availability of arable land. By prohibiting attacks on objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, such as agricultural areas and drinking water, IHL protects these resources from additional conflict-related violence.

7. Humanitarian action must adapt

The climate crisis is altering the nature and severity of humanitarian crises. Humanitarian organizations are already struggling to respond and will not be able to meet exponentially growing needs resulting from unmitigated climate change.

Major efforts – in the form of significant systemic and structural changes, political will, good governance, investment, technical knowledge, a shift in mindsets – are needed to limit climate change.

Humanitarian organizations must collaborate to strengthen climate action. While people in conflict zones are among the most vulnerable to climate change, there is a gap in funding for climate action between stable and fragile countries. A greater share of climate finance needs to be allocated to places affected by conflict to help communities adapt to climate change.

The 10 New Insights in Climate Science 2020 intends to take up the latest and most essential scientific findings in climatology.

1. Improved models strengthen support for ambitious emission cuts to meet Paris Agreement: (1) Earth’s temperature response to doubling the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is now better understood. While previous IPCC assessments have used an estimated range of 1.5–4.5°C, recent research now suggests a narrower range of 2.3–4.5°C; (2) This means that moderate emissions reduction scenarios are less likely to meet the Paris temperature targets than previously anticipated; (3) Improved regional scale models provide better information about heavy rainfall events and hot and cold extremes, offering new opportunities for water resource management; (4) Regional climate predictions can now be made up to a decade ahead with higher skill than previously thought possible.

2. Emissions from thawing permafrost likely to be worse than expected: (1) Emissions of greenhouse gases from permafrost will be larger than earlier projections because of abrupt thaw processes, which are not yet included in global climate models; (2) These abrupt thaw effects could as much as double the emissions from permafrost thaw under moderate and high emissions scenarios; (3) Emissions from permafrost thaw could be yet higher due to effects on plant root activity, which increases soil respiration.

3. Deforestation is degrading the tropical carbon sink: (1) Land ecosystems currently draw down 30% of human CO2 emissions due to a CO2 fertilization effect on plants; (2) Deforestation of the world’s tropical forests are causing these to level off as a carbon sink but this is balanced by greater recent carbon uptake in the Northern Hemisphere; (3) Global plant biomass uptake of carbon due to CO2 fertilization may be limited in the future by nitrogen and phosphorus; (4) CO2 emissions from land-use changes continue to be high in the 21st century and remain a large threat to the land sink.

4. Climate change will severely exacerbate the water crisis: (1) Crises of water quality and quantity are intimately linked with climate change and increasing extremes; (2) New empirical studies show that climate change is already causing extreme precipitation events (floods and droughts), and these extreme settings in turn lead to water crises; (3) The impact of these water crises is highly unequal, which is caused by and exacerbates gender, income, and sociopolitical inequality; (4) Climate change coupled with socioeconomic drivers can impact access to water of good quality; (5) Water-related climate extreme events are contributing to the migration and displacement of millions of people; migration is being treated as an adaptation strategy within the international policy community.

5. Climate change can profoundly affect our mental health: (1) Climate change can directly and indirectly adversely affect mental health over short and longer time scales. Growing evidence suggests the overall burden of mental health impacts of climate variability is high and will increase with additional climate change; (2) Cascading and compounding risks are contributing to anxiety and distress; (3) The mental health consequences of climate variability and change can affect anyone but disproportionately affects those suffering from health inequities; (4) The promotion and conservation of blue and green spaces within urban planning policies as well as the protection of ecosystems and biodiversity in natural environments have health co-benefits and provide resilience.

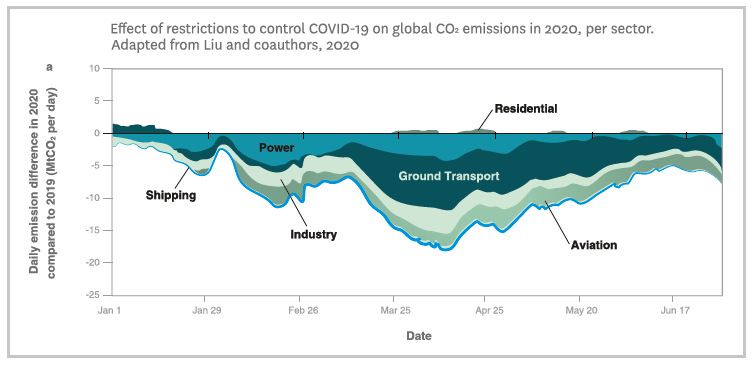

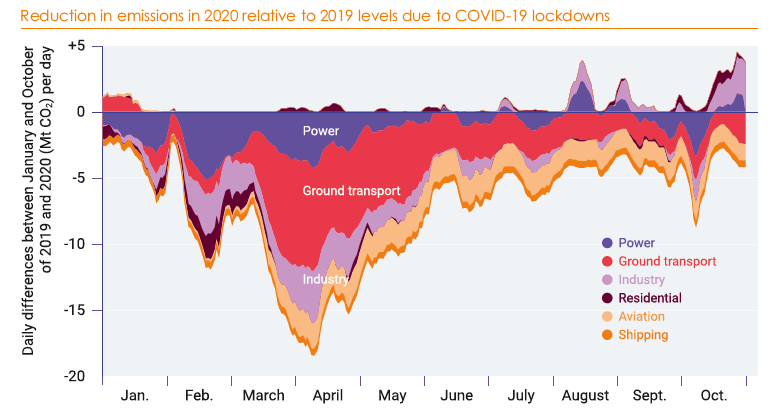

6. Governments are not yet seizing the opportunity for a green recovery from COVID-19: (1) Temporary COVID-19 lockdowns resulted in a large and unprecedented global reduction in GHG emissions and visible improvements in urban air quality; (2) The substantial drops in GHG emissions during COVID-19-induced lockdowns are unlikely to have any significant long-term impact on global emission trajectories; (3) Governments all over the world have committed to mobilizing more than US $12 trillion for COVID-19 pandemic recovery. As a comparison, annual investments needed for a Paris-compatible emissions pathway are estimated to be US $1.4 trillion; (4) Stimulus packages allocated by leading economies for agriculture, industry, waste, energy, and transport, amounting to US $3.7 trillion, have the potential to reduce emissions from these sectors significantly but governments do not seem to be seizing this opportunity; (5) Governments’ economic stimulus packages will shape GHG emissions trajectories for decades to come – for better or worse. If invested in climate-compatible activities, they could be a turning point for climate protection.

7. COVID-19 and climate change demonstrate the need for a new social contract: (1) COVID-19 and climate change exemplify transboundary risks that erode human well-being and economic security, particularly affecting the most vulnerable; (2) The pandemic has spotlighted inadequacies of both governments and international institutions to cope with transboundary risks; (3) Accelerating climate risks require innovative approaches to governance; (4) Some communities and governments have demonstrated that COVID-19 risks can be addressed with innovative local, national, and international responses, and stronger global responses are needed; (5) NGOs, community groups, youth movements, and many other social actors have shown that transboundary responses to global risks of climate change are also possible and there is mounting pressure on governments to act decisively. A new social compact would strengthen the prospects for a humane and just world with a stable climate.

8. Economic stimulus focused primarily on growth would jeopardize the Paris Agreement: (1) A growing number of studies highlight the economic benefits of strategies that stay well below 2°C or even 1.5°C; (2) The costs of renewable energy, battery-electric vehicles, and other low-carbon solutions have fallen dramatically; (3) A COVID-19 recovery strategy based on growth first and sustainability second is likely to fail the Paris Agreement; (4) Investments are needed for a system transition but all must contribute to net energy or CO2 savings in line with the Paris Agreement.

9. Electrification in cities is pivotal for just sustainability transitions: (1) Urban electrification is a powerful pathway to an equitable energy transition; (2) Over a billion people who currently lack access to electricity will benefit from stronger electrification efforts; (3) Reductions in local air pollution and improvements to health and quality of life are tangible co-benefits of urban electrification; (4) An actor-oriented, equity-based approach to the transition will maximize the benefits and mitigate the risks of urban electrification, such as generating a new electrical divide.

10. Going to court to defend human rights can be an essential climate action: (1) Rights-based litigation is emerging as a tool to address climate change; (2) Through such climate litigation, legal understandings of who or what is a rightsholder are expanding to include future, unborn generations, and elements of nature, as well as who can represent them in court; (3) Climate litigation shows cross-fertilization between outcomes in different courts and tribunals, such as national case law influencing responses of international tribunals; (4) Climate-related court cases address harm to people also across national boundaries; (5) Courts come in as “lawmakers” to address climate change, given the absence of adequate climate action in other contexts.

State and Trends in Adaptation Report. On 18 December, the Global Center on Adaptation presented its report “Building Forward Better from Covid-19: Accelerating Action on Climate Adaptation”, the first in a series that will assess progress on climate adaptation and provide guidance and recommendations on best practice in adapting to the effects of a changing climate and building resilience to climate shocks. The report highlights the many successful adaptation initiatives with the potential to be scaled up and replicated. It also fags key policy, skills and finance gaps that must be addressed if adaptation is to be effective and reach those who need it the most.

Climate-change impacts continue to grow in magnitude and frequency. Yet recent progress on adaptation has slowed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following policy recommendations are designed not only to accelerate adaptation and resilience action, but to help the world win back the momentum lost due to COVID. The recommendations are aimed at strengthening:

1. Understanding: To ensure that the risks are fully understood and reflected in the decisions that public and private actors make;

2. Planning: To improve policy and investment decisions and how we implement solutions;

3. Finance: To mobilize the funds and resources necessary to accelerate adaptation.

UNEP issued the 11th edition of the UN Environment Emissions Gap Report (1 December). It assesses the latest scientific studies on current and estimated future GHG emissions and compares these with the emission levels permissible for the world to progress on a least-cost pathway to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. It includes the following key conclusions:

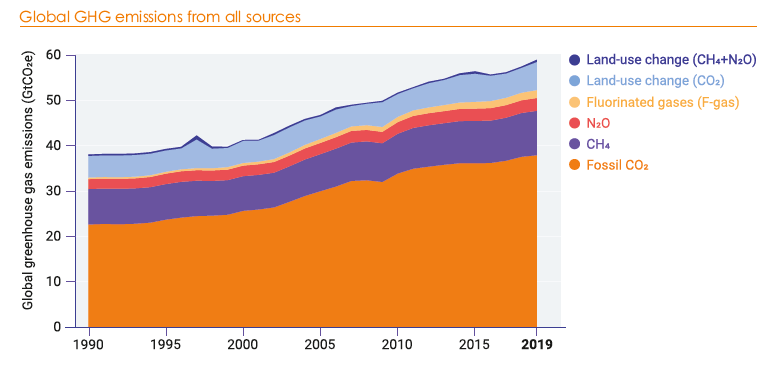

1. Global GHG emissions continued to grow for the third consecutive year in 2019, reaching a record high of 52.4 GtCO2e (range: ±5.2) without land-use change (LUC) emissions and 59.1 GtCO2e (range: ±5.9) when including LUC.

2. CO2 emissions could decrease by about 7% in 2020 (range: 2–12%) compared with 2019 emission levels due to COVID-19, with a smaller drop expected in GHG emissions as non-CO2 is likely to be less affected. However, atmospheric concentrations of GHGs continue to rise.

3. The COVID-19 crisis offers only a short-term reduction in global emissions and will not contribute significantly to emissions reductions by 2030 unless countries pursue an economic recovery that incorporates strong decarbonization.

4. The growing number of countries that are committing to net-zero emissions goals by around mid-century is the most significant and encouraging climate policy development of 2020. To remain feasible and credible, it is imperative that these commitments are urgently translated into strong near-term policies and action, and are reflected in the NDCs.

5. Collectively, G20 members are projected to overachieve their modest 2020 Cancun Pledges, but they are not on track to achieve their NDC commitments. Nine G20 members are on track to achieve their 2030 NDC commitments, five members are not on track, and for two members there is a lack of sufficient information to determine this.

6. The emissions gap has not been narrowed compared with 2019 and is, as yet, unaffected by COVID-19. By 2030, annual emissions need to be 15 GtCO2e (range: 12–19 GtCO2e) lower than current unconditional NDCs imply for a 2°C goal, and 32 GtCO2e (range: 29–36 GtCO2e) lower for the 1.5°C goal. Collectively, current policies fall short 3 GtCO2e of meeting the level associated with full implementation of the unconditional NDCs.

7. Current NDCs remain seriously inadequate to achieve the climate goals of the Paris Agreement and would lead to a temperature increase of at least 3°С by the end of the century. Recently announced net-zero emissions goals could reduce this by about 0.5°С, provided that short-term NDCs and corresponding policies are made consistent with the net-zero goals.

8. COVID-19-related fiscal spending by governments is of unprecedented scale, currently amounting to roughly US $12 trillion globally, or 12% of global GDP in 2020. For G20 members, fiscal spending amounts to around 15% of GDP on average for 2020.

9. So far, the opening for using fiscal rescue and recovery measures to stimulate the economy while simultaneously accelerating a low-carbon transition has largely been missed. It is not too late to seize future opportunities, without which achieving the Paris Agreement goals is likely to slip further out of reach.

10. Early COVID-19 fiscal rescue and recovery measures provide valuable insight for policymakers designing measures for the immediate future.

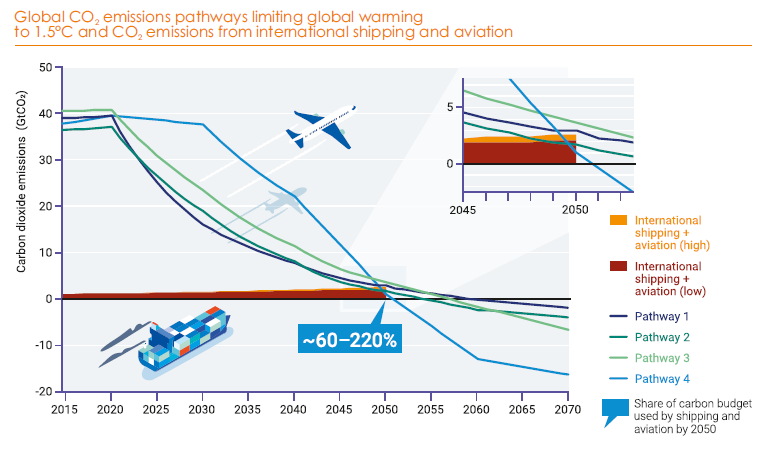

11. Domestic and international shipping and aviation currently account for around 5% of global CO2 emissions and are projected to increase significantly. International emissions from shipping and aviation are not covered under the NDCs and, based on current trends, are projected to consume between 60 and 220% of allowable CO2 emissions by 2050 under IPCC illustrative 1.5°C scenarios.

12. Current policy frameworks to address emissions are weak and additional policies are required to bridge the gap between the current trajectories of shipping and aviation and GHG emissions pathways consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goals. Changes in technology, operations, fuel use and demand all need to be driven by new policies.

13. Lifestyle changes are a prerequisite for sustaining reductions in GHG emissions and for bridging the emissions gap. Around two thirds of global emissions are linked to the private household activities according to consumption-based accounting. Reducing emissions through lifestyle changes requires changing both broader systemic conditions and individual actions.

14. Equity is central to addressing lifestyles. The emissions of the richest 1% of the global population account for more than twice the combined share of the poorest 50%.

The 4th Yearbook of Global Climate Action 2020 was issued. It presents the current range and state of global climate action by non-Party stakeholders (cities, regions, businesses, investors, and civil society), examines the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and opportunities for a green resilient recovery. It also explores the key elements of the Climate Action Pathways, and delivers key messages and reflections from the Champions on the future of the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action.

Major and Significant Events

UNSC organized an Arria formula meeting on the theme of “Climate and security risks: the latest data. What can the United Nations do to prevent climate-related conflicts and how can we climate-proof United Nations in-country activities?” (22 April) and a ministerial-level open debate on “Climate and Security” in an open videoconference (24 July) (see Security Council).

In December UN held a virtual Climate Ambition Summit 2020. Some 70 Heads of State, along with regional and city leaders, and heads of major businesses, have delivered a raft of new measures, policies and plans, aimed at making a big dent in greenhouse gas emissions, and ensuring that the warming of the planet is limited to 1.5°C. The UK announced that it would cut emissions by 68%, compared to 1990 levels, within the next five years, and the European Union bloc committed to a 55% cut over the same time. At least 24 countries announced new commitments, strategies or plans to reach carbon neutrality, and a number of states set out how they are going even further, with ambitious dates to reach net zero: Finland by 2035, Austria by 2040 and Sweden by 2045. Pakistan announced that its scrapping plans for new coal power plants, India will soon more than double its renewable energy target, and China committed to increasing the share of non-fossil fuel in primary energy consumption to around 25% by 2030.

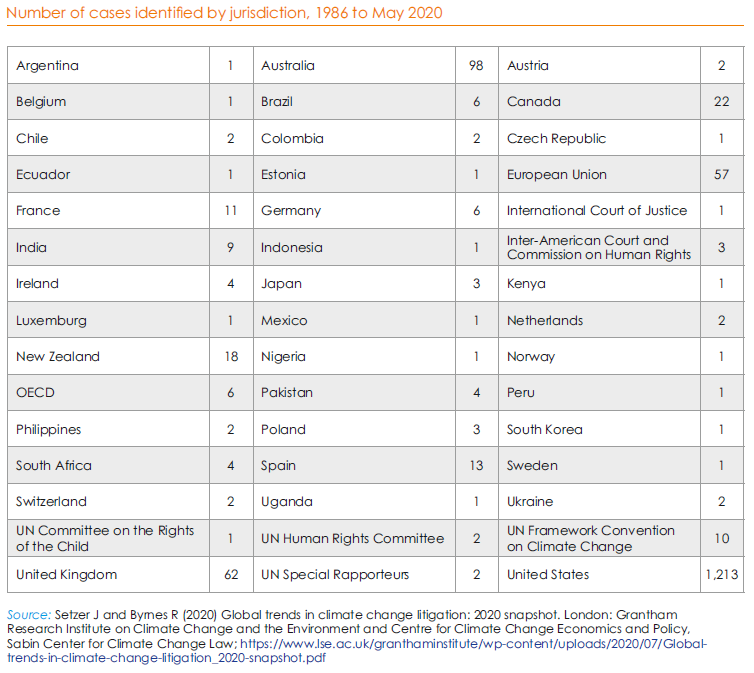

Global trends in climate change litigation in 2020 At the end of May 2020, the Climate Change Laws of the World database featured 374 court cases in 36 countries (excluding the US) and 8 regional or international jurisdictions, as well as 1,872 climate laws and policies in 198 jurisdictions. The Sabin Center’s database for the United States featured 1,213 climate lawsuits in the US up to the end of May 2020.

The UNEP Global Climate Litigation Report: 2020 Status Review provides an overview of the current state of climate change litigation globally, as well as an assessment of global climate change litigation trends. It finds that a rapid increase in climate litigation has occurred around the world. In 2017, 884 cases were brought in 24 countries; as of 2020, cases had nearly doubled, with at least 1,550 climate change cases filed in 38 countries (39 including the European Union courts). While climate litigation continues to be concentrated in high-income countries, the report’s authors expect the trend to further grow in the global south – the report lists recent cases from Colombia, India, Pakistan, Peru, the Philippines and South Africa.

Country Review

European Court of Human Rights. The European Court of Human Rights has told the governments of 33 industrialized countries to promptly respond to a climate lawsuit lodged by six youth campaigners in September. The plaintiffs range from age 8 to 21 and come from Lisbon and Leiria in Portugal. The case states climate change poses a rising threat to the six young people's lives and their physical and mental well-being. It invokes human rights arguments — including the right to life, a home and to family — as well as claiming discrimination.

France. France's top administrative court gave the government a three-month deadline to show it is taking action to meet its commitments on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Republic of Ireland. In July, Friends of the Irish Environment won a landmark case against the Irish government for failing to take sufficient action to address the climate and ecological crisis. The Supreme Court of Ireland ruled that the Irish government's 2017 National Mitigation Plan was inadequate, specifying that it did not provide enough detail on how it would reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

United Kingdom. In December, three British citizens, Marina Tricks, Adetola Onamade, Jerry Amokwandoh, and the climate litigation charity, Plan B, announced that they were taking legal action against the UK government for failing to take sufficient action to address the climate and ecological crisis. The plaintiffs announced that they will allege that the government's ongoing funding of fossil fuels both in the UK and other countries constitute a violation of their rights to life and to family life, as well as violating the Paris Agreement and the UK Climate Change Act of 2008.

USA. As of February, the U.S. had the most pending cases with over 1000 in the court system. In September 2020, the city of Charleston, South Carolina made history Wednesday when it became the first in the U.S. South to sue the fossil fuel industry for damages caused by the climate crisis. The city sued 24 oil and pipeline companies, including major players like ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP and Royal Dutch Shell. The lawsuit contends that the companies knew that their products were heating the global climate but denied the fact in public. It further seeks to charge them for the costs of protecting Charleston from increased flooding and extreme weather events.

Juliana v. United States climate change lawsuit. The first case of its kind, Juliana v. the United States continued in 2020. 21 American teenagers aged from 9 to 20 filed a lawsuit against the US Government. Their complaint asserts that, through the government's affirmative actions that cause climate change, it has violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, as well as failed to protect essential public trust resource . On 17 January 2020, the Ninth Circuit reversed the lower court in the Juliana case, ruling that the plaintiffs do not have standing to pursue their claims because they cannot show that the court has the power to grant the specific remedy plaintiffs seek for the harms they have suffered. On 2 March 2020, attorneys for the plaintiffs filed a petition for rehearing en banc with the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. This petition requests that the full Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals convene a new panel of 11 circuit court judges to review January’s sharply divided opinion.